Calas

Fried rice cakes known as calas were once ubiquitous among New Orleans street vendors.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

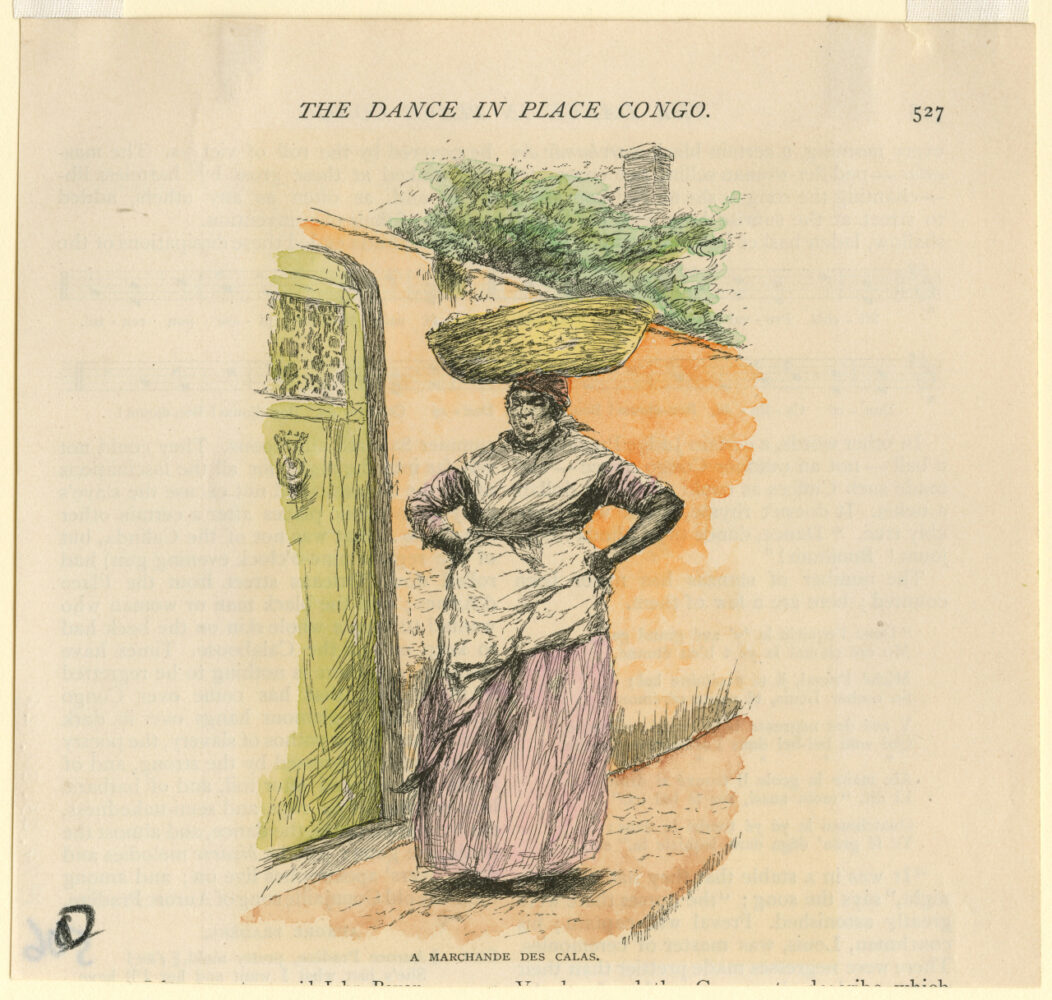

An illustration of a woman selling Calas from a large basket on her head on a street in New Orleans, 1886.

The cala (pronounced ka-LA) is a fried cake that originated with the rice-growing peoples of West Africa, who brought the food tradition with them to the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade. Rice is native to the central Niger delta’s floodplain, where it has been cultivated for more than fifteen hundred years. In the language of the Nupe people inhabiting the Middle Belt of Nigeria, kárá means “fried cake.” The cakes also have ties to the Vai people of Sierra Leone and are still found today in the open-air markets of Liberia, where they are called “calas.”

A simple combination of cooked rice with either rice or wheat flour, eggs, and sugar, dropped into hot oil and fried to a golden brown, calas acquired a mythical status in nineteenth-century New Orleans. Their story bears reflection on the Code Noir, which was established and promulgated in French colonial Louisiana in 1724. With various modifications from the Spanish and Americans, the code established all guidelines regarding interaction between enslaved people, free people of color, and white people. It was finally abolished in 1848, but strict regulations still applied to the lives of Sunday merchants of color. One portion required all enslaved people be allowed to rest on Sundays and holidays. This day “off” provided an opportunity for street vending, but licenses were required and only available to white people and free people of color. Although enslavers often kept the proceeds from street vending, historians believe that some of the earnings helped purchase freedom for enslaved people and their families.

Calas were strictly a street-vending tradition, not sold from stands in the French Market like beignets. Many images and written descriptions of the so-called “cala woman” exist from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, all depicting a Black woman “in quaint bandana tignon, guinea blue dress and white apron,” frying calas in a coal-heated brazier or carrying them wrapped in cloth, balanced in a basket on her head.

Cala vendors were seen in the French Market and on the streets of the Vieux Carré, where a distinctive street call—“Calas, calas! Belle calas tout chaud, Madame! Belle calas tout chaud!”—rang out. Translated as “beautiful calas, very hot,” the call led many to believe that “tout chaud” was part of the official name of the dish. The Christian Woman’s Exchange’s 1885 cookbook Creole Cookery even conflates the rice cake with the vendors themselves, naming its cala recipe “Callers.”

On the early morning streets of the French Quarter, cala vendors found eager customers who answered their calls by purchasing the cakes from their front steps to be enjoyed with a first cup of coffee. The vendors were always waiting outside of St. Louis Cathedral, as the fasting Catholics provided a hungry audience for their wares. However, cala vendors disappeared from New Orleans streets between the two World Wars, though the tradition continued in many Creole homes where they were often served at First Communion breakfasts and on Mardi Gras morning.

The leavening agent of the original African cala was a naturally occurring yeast-like sponge starter. That starter and later commercial yeast cakes required overnight proofing for the dough to rise. The convenience of baking powder eventually shortened preparation time, allowing calas to be made without delay.

The later part of the twentieth century saw calas slip into relative obscurity. However, the international Slow Food movement recognized their endangered status and, with the help of the New Orleans chapter, officially boarded calas onto their “Ark of Taste” in 1999. A renaissance ensued for the ancient dish, and a savory version emerged that can often be found on New Orleans restaurant menus today.