Cholera in Louisiana

During the nineteenth century, cholera epidemics caused tens of thousands of deaths throughout the state of Louisiana.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

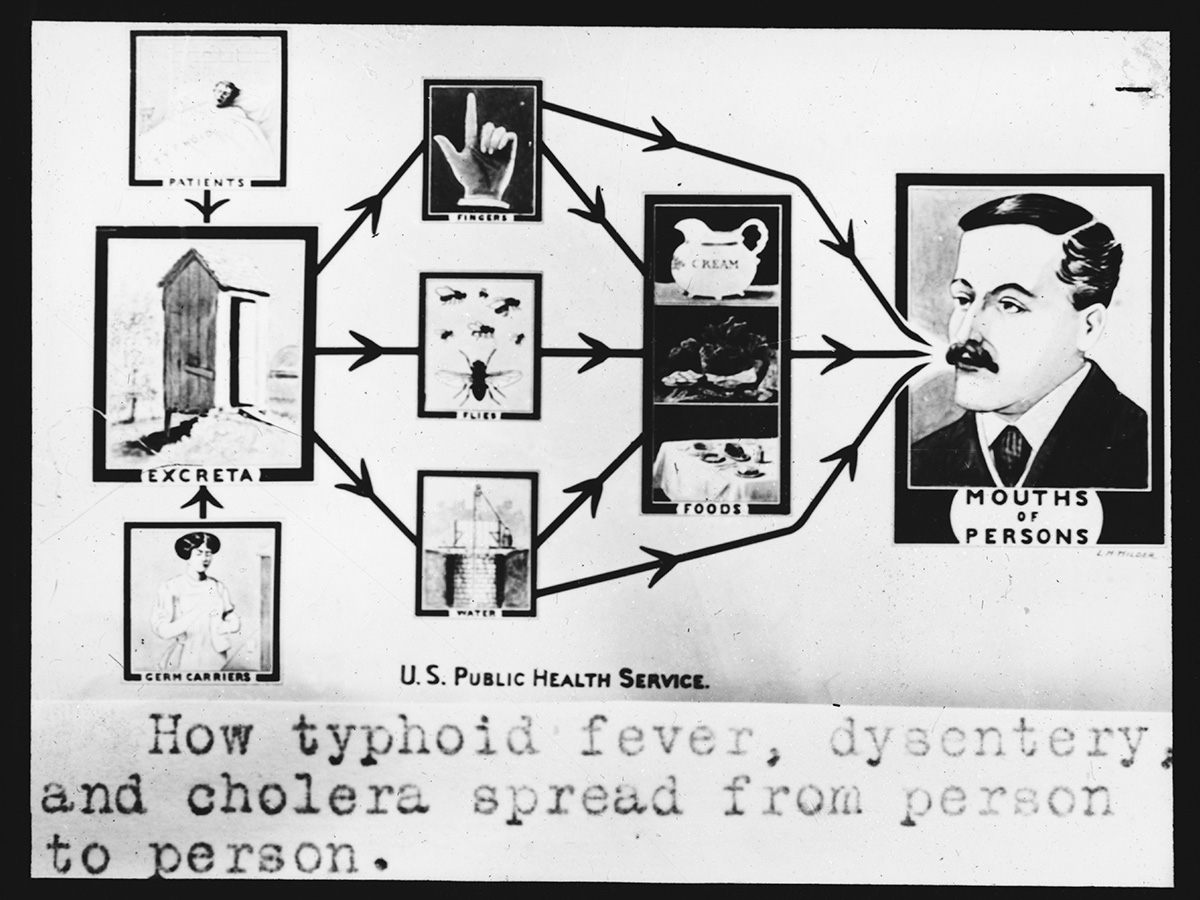

United States Public Health Service poster depicting the transmission of cholera, circa 1920s.

During the nineteenth century, Louisiana experienced multiple outbreaks of cholera, a bacterial infection of the intestine. Cholera epidemics in 1832–1833, 1848–1855, 1866, and 1873 caused tens of thousands of deaths throughout the state. New Orleans was especially hard hit, losing more than seventeen thousand people across these periods. Each of the four major outbreaks occurred within global cholera pandemics. Advances in transportation, high levels of migration, and unsanitary conditions of growing urban centers aided the spread of cholera in the United States. Because medical professionals did not understand the cause of the disease until the 1880s, stopping infections proved difficult. Although not as frequent as yellow fever outbreaks, cholera in Louisiana was deadly and disruptive.

Cause and Symptoms

Cholera is caused by ingesting the Vibrio cholerae bacterium, which is often found in water. The disease is easily spread through unwashed foods and drinking water that has been contaminated by the bodily waste of an infected person. Cholera can cause severe diarrhea and vomiting, accompanied by painful cramps. Loss of fluids can produce acute dehydration, which may leave the skin puckered with a bluish tint and cold to the touch. Without treatment, individuals with these severe symptoms can die quickly. Because cholera is a bacterial infection, individuals can contract the disease multiple times.

Cholera Epidemic of 1832–1833

The arrival of cholera in Louisiana in 1832 occurred within a pandemic that began in India in 1829. Over the next few years, “Asiatic cholera,” as it was often called, spread to Russia, across Europe, and to the British Isles. Transatlantic ships carried the infection to Canada in 1832. It hit New York City in June, spreading west and then down the Mississippi River. By the end of October, the first cases in the state appeared in New Orleans, carried on steamboats from upriver. The city’s lack of water treatment and its poor sanitation practices allowed the disease to quickly spread.

Occurring near the end of a mild yellow fever outbreak, the introduction of cholera to New Orleans proved devastating. Although there was no reliable data collection at the time, it is estimated that five thousand people died over the course of just two weeks—close to ten percent of the city’s total population. At its peak, the epidemic is estimated to have killed five hundred people a day. New Orleanians without access to clean water and who lived in close quarters—poor people, enslaved people, and immigrants—were most susceptible. However, the disease quickly spread through the city and afflicted people of all social strata. Entire households succumbed to the disease. Reverend Theodore Clapp, a preacher who witnessed the epidemic, wrote that “[m]ultitudes began the day in apparently good health, and were corpses before sunset.” So many people perished so quickly that grave diggers could not keep up with the burials. They would arrive at the cemeteries in the morning to piles of bodies left there overnight. In addition to mass graves in the cemeteries, some bodies were discarded in the river and swamps.

Doctors and city officials identified the city’s unsanitary conditions as unhealthy, but they did not understand the cause or transmission of cholera. Because it was commonly believed that “miasmas” or vapors caused disease, city administrators required pitch and tar to be burned on the streets and cannons to be fired to purify the air. Doctors administered a variety of drugs, including mercury chloride, opium, castor oil, cayenne pepper, laudanum, and camphor. These remedies did little to cure patients or stop the spread of the infection.

The high death rate from cholera caused New Orleans to essentially shut down. Trade was suspended, businesses closed, and supplies of some staples, like rice, ran low. Residents who could, fled. This further reduced the city’s population, which was already diminished from inhabitants fleeing yellow fever. The General Charity Committee raised thousands of dollars to assist the sick and the poor. Following a rainstorm on November 7, 1832, cholera cases began to abate. With the arrival of a frost on November 11, the threat of yellow fever ended, while cholera cases continued to decline. Normal commercial activity began to resume in New Orleans. However, the city experienced a second cholera outbreak from May to June in 1833 that killed an estimated one thousand people. The following year, doctors with front-line cholera experience founded The Medical College of Louisiana, today known as Tulane University School of Medicine, the first medical school in Louisiana.

Cholera spread from New Orleans to other parts of Louisiana by infected passengers on steamboats, following major waterways that connected plantations, towns, and villages to the port city. Throughout 1833 cholera infections circulated in the state, moving along the Mississippi River above and below New Orleans, westward along Bayous Lafourche and Teche, and into areas along the Red River. On some plantations, the death rate among enslaved laborers was so high that crops were left unharvested.

Cholera in 1848–1855

Louisiana remained cholera-free for over a decade, but the disease returned in 1848. For the next six years a series of outbreaks once again caused widespread illness and thousands of deaths. In New Orleans alone, nine thousand people perished.

This epidemic followed a pattern similar to the previous one. It arrived in New Orleans with German immigrants on transatlantic ships in December 1848. The city board of health downplayed the outbreak, but as case numbers continued to rise, residents panicked. Economic activity slowed as people fled the city. Steamboats headed upriver were packed with New Orleanians hoping to escape cholera and recently arrived European immigrants. As one report explained, “Every steamboat upon the river became a moving pest-house,” spreading the disease throughout the Mississippi River valley. Within Louisiana, cholera spread along the Mississippi River and other waterways, afflicting parishes as far north as Morehouse and Caddo and as far west as Iberia.

The waves of cholera outbreaks in New Orleans between 1848 and 1855 corresponded with some of the highest numbers of immigrant arrivals to the port. Infected passengers on transatlantic ships continued to bring cholera to the city. Concerned with the transmission of infectious diseases, especially yellow fever, the state legislature passed a law that created the Louisiana State Board of Health in 1855. The board was tasked with setting up a quarantine system to screen for yellow fever, cholera, and other diseases aboard ships.

Cholera in 1866 and 1873

Cholera returned to Louisiana twice after the Civil War. The first outbreak occurred in 1866. Federal troops from New York, where cholera cases began to appear in late spring, may have brought the disease to New Orleans in July. However, most of the thirteen hundred cholera deaths in the city occurred in August and September, making the source of this outbreak unclear. From New Orleans, the disease spread up the Mississippi River to St. John the Baptist, Iberville, East Baton Rouge, West Baton Rouge, Concordia, and Catahoula Parishes. It also struck areas along the Red River, including Alexandria and Shreveport. The following year, cholera killed almost six hundred people in New Orleans.

Louisiana was one of nineteen states afflicted in 1873, the year of the last cholera epidemic in the United States. It began in New Orleans in February. By November, 259 people in the city had died. In the spring and early summer, the epidemic hit nine parishes in the southwest and northeast parts of the state, killing less than three hundred people total.

The outbreaks in 1866 and 1873 were much less devastating than the previous epidemics—due, in part, to a better understanding of the disease. Research by Dr. John Snow in London uncovered the connection between cholera and a contaminated water supply in 1854. In 1866 the Louisiana State Board of Health and the New Orleans City Council passed a health ordinance that included sanitation measures, regulations on privies (outdoor toilets), and the appointment of health officers to monitor and report on conditions in the city. Baton Rouge passed a sanitation law to undertake similar actions. Unfortunately, both cities enacted these measures after cholera had spread, making their impacts less effective.

Cholera Today

Large-scale cholera outbreaks still occur in places throughout the world where sanitation is inadequate and clean water is not accessible. Treatment is simple and effective, if administered quickly. Due to water treatment and other sanitation practices, Louisiana has not experienced a cholera epidemic since 1873. However, a few cases of the disease, traced to undercooked shellfish consumption, were reported in Louisiana between 1978 and 2005.