“Land of the Defunct Orange Tree and Ice-Burdened Palmetto”

The Great Arctic Outbreak of 1899

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

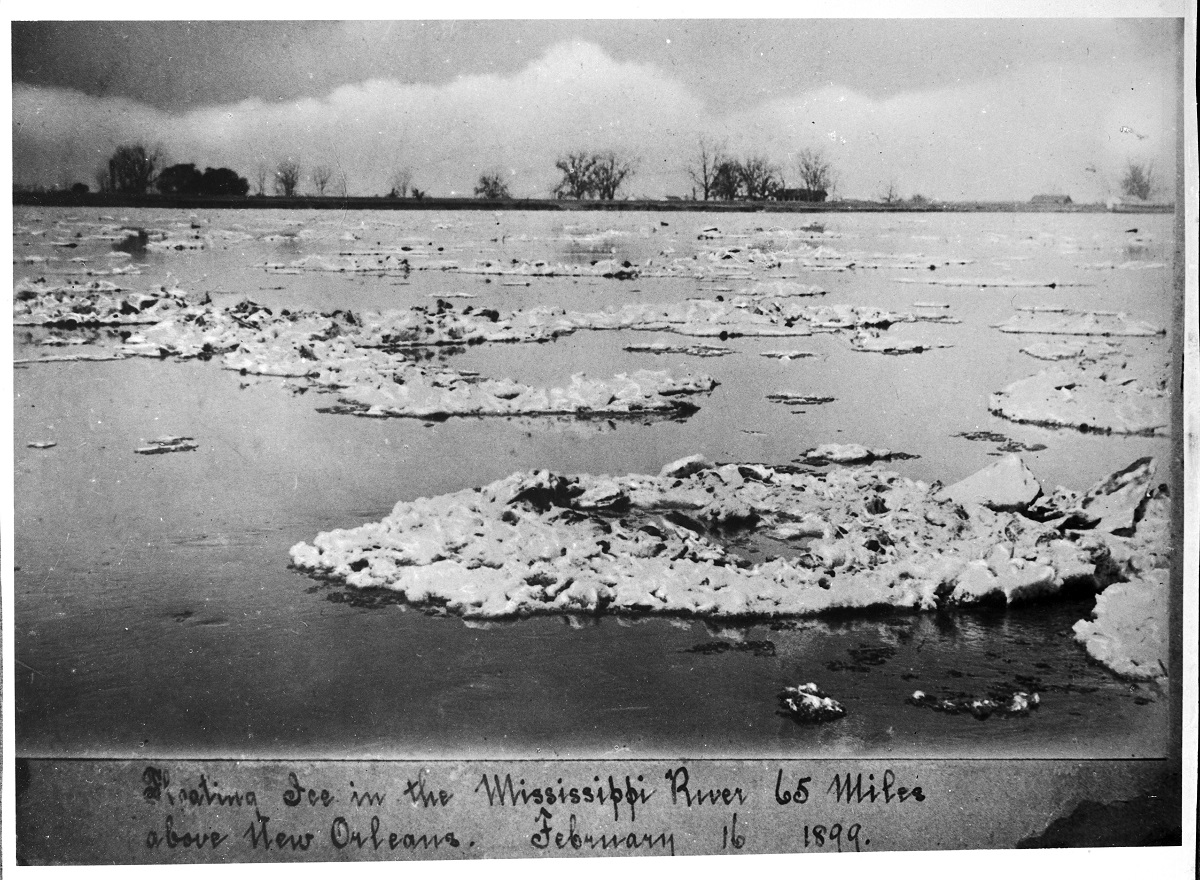

Odile Schexnayder Collection, Louisiana State Museum

Edgard residents observe ice on the Mississippi River.

The temperature hit zero in each of the forty-five states in the union at the time, and waterways that had never frozen before were covered in ice. The Mississippi River froze to a complete standstill north of Cairo, Illinois, and the storm set temperature and snowfall records across the country—many of which still stand. East of the Rocky Mountains, much between the two systems froze solid in a matter of days.

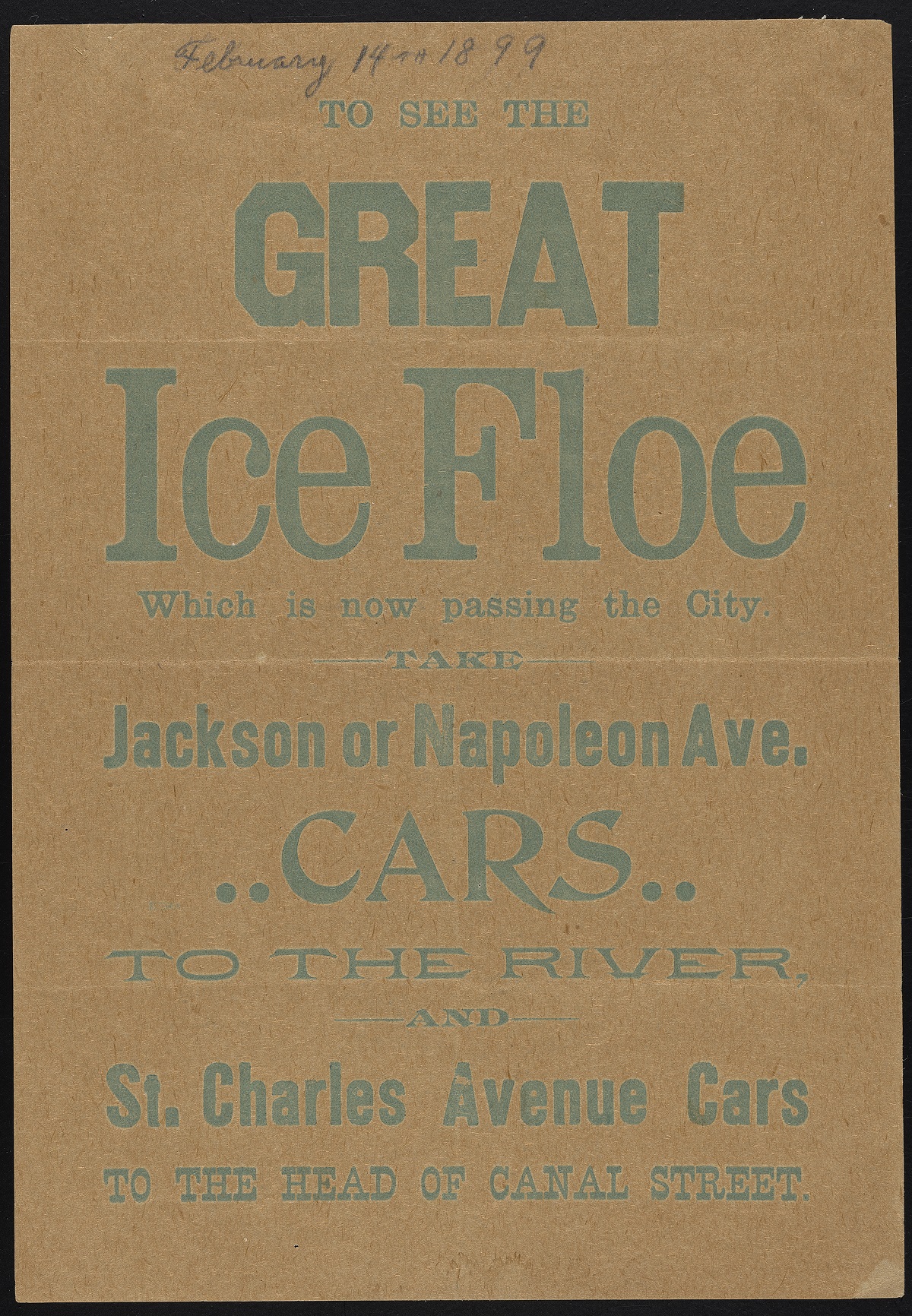

February of 1899 remains the only real blizzard on record that Louisiana has ever suffered. No part of Louisiana was prepared for it. Authorities measured four inches of snow in New Orleans between February 12 and Valentine’s Day. But it did not melt in the typical several hours—instead, the mercury continued to drop. New Orleans and Baton Rouge recorded temperatures in the single digits on February 13, and the next day—Mardi Gras, as luck would have it—the streets of the French Quarter were covered in ice and snow, and the average temperature was around 30 degrees, making it the coldest, and possibly most unpleasant, Mardi Gras on record. Three days later, on February 17, New Orleanians woke up to a wild sight: tiny icebergs floating down the Mississippi River.

The snow-delayed parades in New Orleans were just the tip of the mini-iceberg. Stories told in newspapers from 1899 trace the blizzard’s path of sub-freezing temperatures from Lake Providence to Houma, and from St. Martinville to Minden—where Louisiana’s current cold temperature record was set on February 13, 1899, at sixteen degrees below zero.

Ice on the Mississippi. Gift of Allan Phillip Jaffe, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Chaos on the Mississippi

In the easternmost corner of northern Louisiana, people in the town of Lake Providence huddled inside during Mardi Gras of 1899. Because the weather had been cold even before the blizzard, the town had exhausted its winter supplies of wood and coal—its primary sources of heat—at a faster rate than usual. The blizzard brought Lake Providence down to four degrees below zero. Coal shipments, which were transported by barge on the Mississippi River, had been delayed after the cold snap froze the river in Illinois. The ice floating downriver made the river virtually impossible to navigate safely. Even for vessels that were docked, the floating ice brought chaos, and meant trouble for the southern coal supply. Because of the town’s proximity to the river, residents of Lake Providence had a front-row seat to the unfolding disaster.

“Four or five coal barges passed down the river on Tuesday, broken loose from Greenville or Arkansas City by the heavy floating ice,” reported the Banner-Democrat in Lake Providence on February 18, 1899. “Those who saw the barges say they were deep in the water, showing that they were loaded with coal.” In the same issue, the Banner-Democrat reported that a Captain John B. Scruggs arrived by tugboat on the Wednesday after the storm, looking for twelve missing barges full of Pittsburgh coal that broke loose at Greenville, Mississippi, because of floating ice. Captain Scruggs claimed the missing barges contained 250 thousand bushels—or ten thousand tons—of coal. He was hopeful that he could chase down half of it.

Meanwhile, half of Lake Providence had run out of wood to burn, and the local school had run out of coal, noting that all they had to burn was “fine dust.” Produce and bottled goods froze inside of closed grocery stores, and livestock froze to death. The Banner-Democrat reported the death of at least one person—a Black man who arrived at the police station “nearly frozen stiff.”

“All of them had wood enough to carry them through an ordinary winter, but such a winter as the present one is unprecedented in this part of the country,” the Banner-Democrat observed. “We were unprepared for it, our houses are not built to keep out such intense cold, and everyone more or less suffered.”

Walking on the Bayou Terrebonne

“With frozen machinery, frozen type, frozen ink and frozen fingers the wonder is, not that the Courier gets out in scanty shape, but that it gets out at all,” reported the Houma Courier on February 18, 1899. “The Courier is about as poorly prepared to cope with the zero weather of the past week as other establishments that are located in this land of the defunct orange tree and ice-burdened palmetto.”

Temperatures in Houma dropped to four degrees on the evening of February 13. Bayou Terrebonne froze solid, as did water pipes, orange and other fruit trees, and vegetable gardens. The farmers feared that their sugar cane crops were devastated. “[Professor William Carter] Stubbs, after examining . . . the stubble he had in the Experimental Station where the land was well drained, found that every vestige of life had been destroyed in the cane, and gives as his opinion that the loss in the sugar section will be tremendous,” the Courier reported.

Along with the difficulty of publishing a Louisiana newspaper in prolonged zero-degree weather, the paper detailed the novel joy of winter antics: “Skating on the bayou no doubt would have been fine, but, not being used to such things, the people of Houma were too cautious to indulge in the luxury of a skate. . . . Sleighs were hurriedly constructed on a somewhat rude, but serviceable scale, and sleigh rides were indulged by many of the residents. Dinner bells, cow bells, and sundry other bells were carried by the sleigh riders, that nothing might be lacking, to make the riders as much a la zero as it was possible to make them.”

Frozen Cattle in St. Martinville

On February 11, three inches of sleet and snow fell just southeast of Lafayette in St. Martinville, coupled with temperatures as low as sixteen degrees. Butchers were unable to cut their frozen meat, and milkmen were unable to deliver frozen milk. Water and other liquids froze inside of fire-heated brick homes, and outside, cattle froze to death under what was usually adequate shelter. “Even in the house by the fire, the temperature was lower than the freezing point,” the St. Martinville Weekly Messenger reported on February 18.

The Weekly Messenger also reported a rumor that all orange trees in Louisiana had died due to the blizzard, and that some locals had resolved to shift away from growing oranges: “The people hereabout have given up the idea of cultivating oranges, as every four or five years we have a cold spell that destroys them just at about the time they would bear fruit.”

A handbill offers directions to see the ice floe. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Minden, Louisiana

In Webster Parish, just east of Shreveport, the town of Minden had already been in winter survival mode for a week when the cold blast hit North Louisiana. Based on the newspaper reports prior to the blizzard, they did not expect it to get colder.

“The cold wave has passed off and everybody is in high spirits,” the Webster Signal reported on February 3, 1899. “Nothing has been done here for the past week except get wood and make fires and feed and shelter stock to keep them from freezing. The heaviest snow fell here last week that has fallen here in many years. The ground was frozen when the snow began to fall, and it continued turning cold until it about reached the ‘cold Friday.’ It is said the ice was five inches thick in the mill pond. Public schools are all stopped until warmer weather.”

There are no archived issues of the Webster Signal for the rest of February. Minden’s Weather Bureau recorded a temperature of sixteen degrees below zero and seven inches of snowfall a little over a week after this issue printed. While it’s possible the Webster Signal did publish other issues in February 1899 that are not archived, it’s also possible that the Signal’s newspaper ink, like the Courier’s, simply froze.

A report on the blizzard of 1899 was prepared in 1988, nearly a century later, for the American Meteorological Society. The report notes, “The February 1899 outbreak was unique in its capacity to chill and bury a large section of the nation. Therefore, whenever very cold and snowy conditions return to the United States and reports begin to circulate that the present weather is ‘the worst,’ ‘coldest,’ or ‘snowiest,’ forecasters and weather observers can always refer to February 1899 as a benchmark with which to compare similar events.” After fourteen pages of in-depth analysis on the atmospheric phenomena at work in February of 1899, the report concludes that the storm set a new standard for winter storms—one that endures today.

Christie Matherne Hall writes about foodways, culture, travel, and natural disasters for 64 Parishes and Country Roads. She is also a podcast producer for the Western Colorado Writers’ Forum and an editor for wallethub.com, and enjoys helping people write their memoirs through the Story Terrace platform.