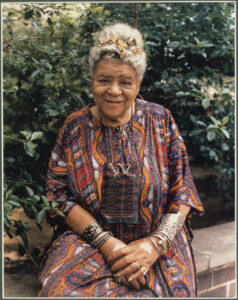

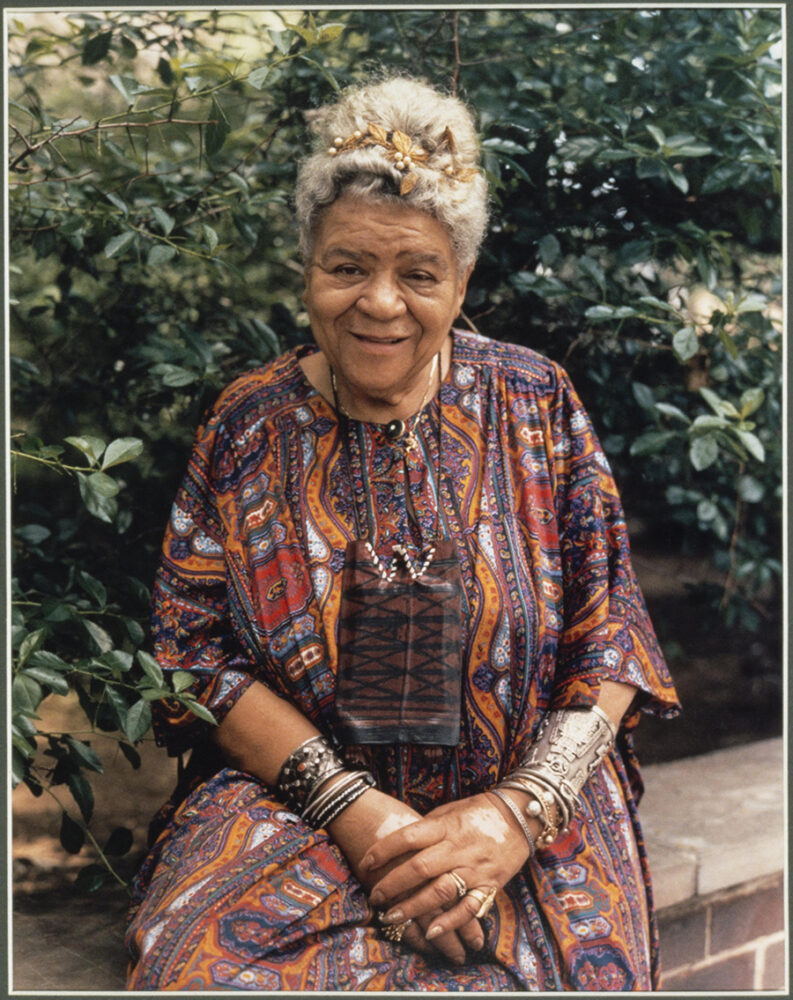

Audley Moore

Due to her tireless grassroots organizing efforts, Audley Moore was known as “Queen Mother” of the Black Freedom Movement and the modern reparations movement.

Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Portrait of Audley Moore, 1982. Judith Sedwick, photographer.

Audley Moore was a lifelong organizer who shaped the scope and trajectory of the twentieth-century Black freedom struggle from the 1920s to the 1990s. Moore’s political life began in New Orleans when she became a follower of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). She rose to national fame as an organizer within the Communist Party in New York City, which in the 1930s and 1940s supported Black nationalist principles. When the Red Scare suppressed her organizing networks, Moore returned to Louisiana, developing her own radical grassroots organizations in the 1950s and early 1960s. These organizations linked early- and late-twentieth-century Black radical organizing and introduced a new generation of organizers to nationalist activism. Moore went on to mentor or advise many late-twentieth-century luminaries including Malcolm X. She spent the 1980s and 1990s touring the world, appearing alongside movement notables like Nelson Mandela, and galvanizing support for reparations through Black nationalist groups. Because of her tireless efforts, she earned the title of the “Queen Mother” of the Black Freedom Movement. She was also known as the mother of the modern reparations movement due to her grassroots organizing that jumpstarted reparations activism in the mid-twentieth century. Although she had a global reputation, Moore began her activist journey in New Orleans and always considered Louisiana home.

Early Life and Activist Beginnings

Audley Adeline Moore was born in New Iberia on July 27, 1898. She was the oldest daughter of St. Cyr and Ella Moore. It is likely that Moore’s father made the transition from slavery to freedom after the Civil War in Iberia Parish and found it to be a place of possibility for a young Black man. He found success working in the lumber business and became a constable in Jeanerette during the late 1860s. Moore’s mother, Ella Johnson, was born to parents who lived in St. Landry Parish. Ella spent her early life in Opelousas before migrating to Jeanerette, where she eventually met and later married St. Cyr Moore. As a young Black couple seeking prosperity at the end of the nineteenth century, the pair moved to New Orleans.

Audley and her two younger sisters, Loretta and Eloise, enjoyed an idyllic girlhood with a single-family home, an all-girls Catholic school education, and music lessons—rarities for young Black girls growing up in the Jim Crow South. However, this prosperous life quickly evaporated when both of Moore’s parents died, leaving her to care for her two younger sisters as a teenager in New Orleans. Moore became a domestic worker—the primary form of work available to Black women in the early twentieth century. Cleaning and cooking in white households opened Moore’s eyes to racial, sexual, and social dynamics that her parents tried to shield her from.

Perhaps seeking the security that only marriage could provide, Moore married a Jamaican sailor named Josiah Spraggs on July 26, 1920. The union transformed her life. Spraggs introduced her to Marcus Garvey and the UNIA. As founder of the largest Black organization the world has ever seen, Garvey preached Black pride, self-determination, and self-sufficiency—the cornerstones of Black nationalism. New Orleans was a UNIA stronghold and home to the organization’s largest chapter in the South. Moore claimed that she heard Garvey speak in defiance of white police officers during his 1917 visit to the city and began the transformation from a self-professed “bourgeois little stinker” to one of our nation’s Black nationalist leaders then and there. She was a lifelong member of the UNIA and began her journey as an organizer in the early 1920s. She and Spraggs then migrated to Harlem, New York—the location of UNIA headquarters.

Activism in Louisiana

Moore spent several decades in New York working for civil rights organizations and the Communist Party before returning to Louisiana in the late 1950s. When she joined the organization, the party promoted the “Black Belt Thesis,” or the idea that African Americans had the right to secede and form a separate nation on American soil. This aligned with Moore’s politics as a Garveyite, and Moore called the party a “wonderful vehicle” to help her organize for Black rights. She engaged in rent strikes, school desegregation struggles, voter registration drives, and women’s and civil rights organizing. This impressive activist agenda gained her national recognition as an activist. Once back in her home state, Moore and her sisters took over the house on Daneel Street that her father once owned and started the modern reparations movement through her New Orleans-based group, the Universal Association of Ethiopian Women (UAEW). From 1957 to 1963 this small group of Black women led the fight against racism and sexism in New Orleans. During its short but impactful existence, the UAEW helped exonerate men in Angola Prison wrongly accused of rape, fought for welfare rights for Black women in Louisiana, and began organizing for reparations to be paid for the atrocities of slavery and Jim Crow. Although Moore would not consider herself a feminist, her work in groups like the UAEW centered Black women’s experiences and prioritized their gender-specific political and social concerns.

Later Years

By the early 1960s Moore was a sought-after activist and advisor and returned to New York City. For the rest of the twentieth century, she nurtured Black nationalists and reparations organizing through Black Power-era organizations such as the Republic of New Africa and the Black Panther Party. From the 1970s to the 1990s Moore served as a mother and mentor of the radical Black Liberation Movement, taking on the honorific “Queen Mother.” She was a sought-after teacher and theoretician who traveled globally and was especially well received in newly liberated African countries such as Uganda, Ghana, Tanzania, South Africa, and Nigeria. Moore died in Brooklyn, New York, on May 2, 1997.