Zwolle Tamales

Zwolle tamales, a popular food from northwest Louisiana’s Sabine Parish, trace their origin to the region’s Indigenous cultures.

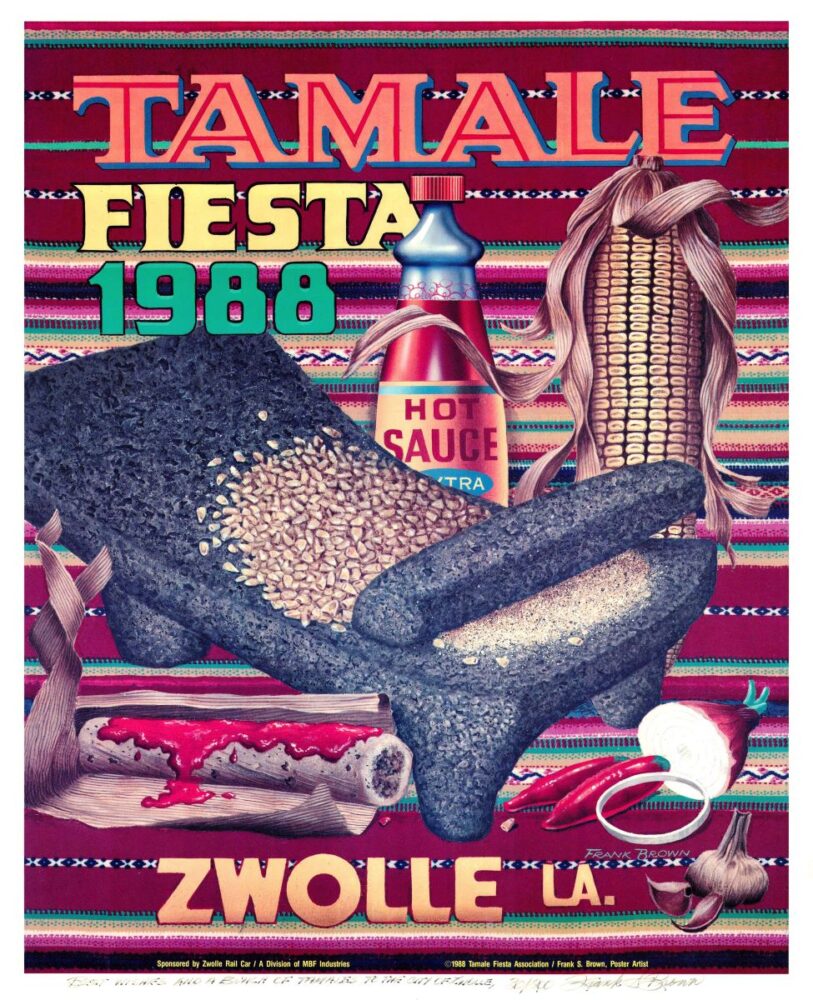

© 1988 Tamale Fiesta Association. Photo courtesy of Cody Bruce.

Official 1988 Zwolle Tamale Fiesta poster with art by Frank S. Brown.

Zwolle tamales are a popular regional food that take their name from a town in Sabine Parish. Heat-and-serve Zwolle tamales are available in hot and mild varieties in the frozen food section of grocery stores in Louisiana. The second week in October features the Zwolle Tamale Fiesta, the largest festival in Sabine Parish, at the Zwolle Festival Grounds.

Origins

Louisiana is widely recognized for its Cajun and Creole cuisines. Gumbo, one of the state’s most iconic foods, is often used as a metaphor for Louisiana’s ethnic and cultural makeup. However, northwest Louisiana’s foods, many of Indigenous origin, are relatively unknown. These include the Natchitoches meat pie, “pepper” (a chili pepper concoction similar to, but less watery than, salsa), and a range of corn-based foods—including the iconic Zwolle tamale.

Zwolle tamales trace their origins to the Zwolle-Ebarb area’s Choctaw-Apache Tribe. That community—descended from the Adai, Lipan Apache, and Choctaw peoples, as well as people indigenous to Mexico, French traders, and Spanish soldier-settlers—blended into a distinct local culture with unique food influences. The form of tamales made in Sabine Parish is much older than the better-known Mississippi Delta tamales, “Tex-Mex” tamales, and those introduced from Mexico during twentieth-century migrations. When Spanish priests and mestizo soldier-settlers came to the region in the early eighteenth century, Indigenous peoples were already eating tamales and other corn-based foods cooked in the shucks of corn, known as shuck breads. During the eighteenth century, Parisian nobleman-turned-Natchitoches-leader Athanase de Mézières reported a Caddo chief offering him tamales, but the tradition has been lost among the present-day Caddo in Oklahoma. Choctaw people in both Oklahoma and Mississippi have banaha, a shuck bread similar to tamales but made with cornmeal and peas. Mexican vassals from points south, including Saltillo and Coahuila, Mexico, brought their own tamale traditions. Zwolle tamales developed out of this interaction between different ethnic groups and tamale traditions and survived in the Native ethnic enclaves of the region, especially in the Zwolle-Ebarb area of Sabine Parish.

Preparation

Tamales are made with various fillings, but modern Zwolle tamales are almost invariably made with pork. Making the tamales from scratch is tedious since one must turn dried corn into masa (dough) and adequately prepare the filling. In times past the process involved taking dried corn kernels and butchering a hog, which, prior to refrigeration, was best done in fall or winter. While commercial masa is now available in grocery stores, Zwolle tamale makers continue to make dough from scratch. Doing so involves boiling dried kernels in an alkaline solution, a process known as nixtamalization, to make hominy. After thorough washing, the hominy is ground into dough. The meat must be prepared, usually with dried cow horn peppers or other chilies along with garlic and other spices. The corn shucks are then filled, followed by steaming or boiling.

Modern Production and the Zwolle Tamale Fiesta

Tamales are usually made in large quantities, sometimes by the hundreds of dozens. In times past tamales were not sold but distributed among extended kin. Traditionally food was part of expected hospitality to family, friends, and even unexpected visitors, but after World War II, expectations began to change. Many area residents shifted from a mix of hunting, gathering, and farming supplemented by other jobs to wage work exclusively, limiting their time for collective activities and shifting their ideas about reciprocity. An additional shift came in the 1960s, when the states of Louisiana and Texas flooded the Sabine River to create Toledo Bend Reservoir, the largest artificial lake in the South. The flooding destroyed the bottomlands, which were customarily used by the local Indigenous community for free-ranging livestock, gathering wild food, and hunting. The resulting tourist economy drove year-round demand for the spicy pork and dough-filled golden treats, which were popular with longtime residents and newcomers, and tamale houses sprung up to meet that demand.

Rogers P. Loupe, an agricultural educator born in 1916 to Cajun parents in Whitehall, came to Sabine Parish after World War II and married local Mary Ruth Ebarb. After the Toledo Bend Reservoir’s construction, Loupe became a well-known civic booster and tourism advocate. He proposed creating a local festival, and in 1975, the Zwolle Tamale Fiesta was born. Since 1985 the festival’s annual poster contest has become a major feature in the leadup to the main event. Volunteer organizers work year-round to ensure a successful fiesta.

The specific components of the festival have changed over time. The town boasts event grounds in downtown Zwolle, where most activities occur. Mainstays include a pageant, which includes Spanish costumes, a court, Catholic mass, street parade, tasting contest, tamale-eating contest, trail ride, and nightly live music. A popular mud-bogging contest—where participants traverse a slough of mud using raised four-wheel-drive trucks—is held on Saturday afternoon.

Some locals have criticized the festival organizers for relying on stereotypes of Mexican culture painted in murals and temporary public art around town. They argue the event should instead highlight the area’s unique blend of Spanish and Indigenous cultures. Others have noted that organizers tend to prioritize Spanish themes over Indigenous ones. For example, corn feasts, family-based tamale-making, and “feeds” (large meal gatherings) existed centuries before Loupe’s fiesta. However, such events were generally private and meant exclusively for community members rather than tourists.

Today Zwolle tamales retain many meanings. In addition to a delicious food, for many the dish is synonymous with the Zwolle Tamale Fiesta, an excuse to eat and drink, and an occasion for fun with family and friends. Some see it as representative of the rich history of the Parish, a synthesis of Spanish culture of the eighteenth century and the Catholic religion they brought with their missions. The Zwolle tamale remains a local ethnic marker and a living example of the persistence of Indigeneity.