“Sarcasm of Fate”

The imposing life and unceremonious death of Captain Thomas P. Leathers

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

Captain Thomas P. Leathers.

Murphy Library Special Collections/ARC, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse

When Thomas P. Leathers, captain of seven successive steamboats called the Natchez, started to walk across St. Charles Avenue on the evening of May 25, 1896, he saw a couple cycling toward him on a tandem bike, and stopped to let them pass.

The couple may have recognized him: Leathers’s “commanding form and fine, aristocratic face, crowned with snowy hair and beard, always arrested attention,” according to an 1896 edition of the Daily States, and the Daily Picayune, in that same year, called him one of New Orleans’s “best known men,” a national celebrity ever since his 1870 steamboat race against a rival pilot up the Mississippi River garnered breathless media coverage.

Prominent as he was, he was invisible to a cyclist pedaling for all he was worth to pass the tandem bike. The cyclist slammed into Leathers at full speed, plowing him face-first into the asphalt. After tumbling onto the street behind him, the cyclist saw the blood flowing over Leathers’s white hair and beard, scrambled back onto his bike, and fled into the twilight.

Bystanders called an ambulance, and after Leathers’s wounds were dressed, he was carried two blocks to his mansion at the corner of Carondelet and Josephine Streets. The next day, the Times-Democrat offered no details on his condition, but reported optimistically, “It is not thought that he is dangerously hurt.”

This confidence in Leathers’s recovery was likely buoyed by his storied history of triumphs over deadly crises on the river. In a profile for the New York Evening Post, later reprinted in her 1887 book Southern Silhouettes, journalist Jeannette H. Walworth hailed his legendary strength: “The elements . . . have transmuted some of their subtle forces into his hardy veins,” she wrote, paying him “tribute in rich blood and boundless vigor.”

Leathers had bounced back from political disaster, too, though those maneuvers received far less attention. Just a week earlier, he’d quietly notched an epochal victory when the US Supreme Court issued its Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, affirming the constitutionality of “separate but equal” racial discrimination. As Leathers lay bandaged in bed, few realized that a Reconstruction-era legal battle he fought had helped lead to the entrenchment of Jim Crow.

Leathers “owned a great many negroes” before the Civil War, according to an 1896 article in the Times-Democrat, and he made a fortune from the stolen labor of countless others: He built each successive boat named Natchez to carry more cotton than the last, ultimately bringing to market upwards of a million bales by his estimate.

He paid some Black employees, too, including Pinckney B. S. Pinchback, who would become a greater antagonist to Leathers than any rival steamboat captain. The son of a white plantation owner and a Black woman he’d recently emancipated, Pinchback was born free, but after his father died he had to find work on riverboats to support his family. At some point during Pinchback’s teens, in the 1850s, Leathers hired him to do odd jobs on his “floating palaces,” as his well-appointed boats were called. Pinchback worked at Leathers’s side for a while, but moved on probably by 1860.

Around that time, with the future of slavery under threat, Leathers joined calls for Louisiana to secede from the United States. When his friend Jefferson Davis was elected president of the Confederacy, Leathers leant him Natchez No. 5 to travel to his swearing in.

Shortly after federal forces took control of New Orleans in 1862, Pinchback made his way to the city and raised companies of Black soldiers to fight for the Union. Leathers, too old to take up arms, gave the Natchez to Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard to use in battle; Union shelling destroyed its custom-woven Belgian carpet and bronze chandelier. Leathers was later arrested by federal forces as a Confederate spy, then pardoned by President Johnson after the war.

Back home on Carondelet Street, Leathers refused to accept that the insurrection failed. He continued to wear Confederate gray, and flew the stars and bars on Natchez No. 6.

Meanwhile Pinchback climbed the ranks of radical Republican politics. In 1868 he drafted a provision of the new Louisiana constitution guaranteeing “equal rights and privileges upon any conveyance of a public character” regardless of race. Leathers defied it, keeping his boats segregated. Then, in 1869, Pinchback drafted a state law that gave victims of racial discrimination the right to sue for damages.

On July 20, 1872, Leathers was an esteemed guest on a steamboat that temporarily took over the Natchez’s route between New Orleans and Vicksburg. He observed as Josephine Decuir, a recently widowed Creole of color heading to her plantation in Pointe Coupée Parish, was denied admittance to a stateroom reserved for “white ladies.” After spending the night in a small recess in the rear of the boat, she filed a lawsuit under Pinchback’s law, and Leathers became a star witness for the defense.

The case addressed a central question of Reconstruction, one embodied in Leathers’s relationship to Pinchback: could the new governing regime exercise power over the white elite that had so recently subjugated its Black officials? In his testimony, Leathers said that he saw Pinchback, who’d served as state senator, lieutenant governor, and, in an acting capacity for thirty-six days, the first Black governor in United States history, as “the same man he was when he was with me as cabin-boy.”

Leathers also testified that segregation was an economic necessity for riverboats because “a large majority of the white” ticket-buyers “do not wish to travel mixed up with the colored people.” If they were forced to do so, ridership would plummet. He asserted that “colored people” wanted separate accommodations, too, despite the glaring counterexample of Mme. Decuir. In any event, Leathers said, “I don’t propose to give up charge of my steamboat to . . . Pinchback . . . or anybody else, white or black.”

A New Orleans judge ruled in Mme. Decuir’s favor, and the Louisiana Supreme Court upheld the decision in 1874. With his bottom line and his sense of autonomy at stake, Leathers, along with a few other boat captains, pledged financial backing to appeal the case to the US Supreme Court. (Disdainful as he was of federal authority, he was willing to solicit it to serve his interests.)

In 1877, before the high court ruled in the Decuir case, waning political support for Reconstruction brought it to an end. Author Manly Wade Wellman writes in Fastest on the River (1957) that when federal troops left New Orleans and Pinchback’s Republican party lost power, Leathers “watched with ferocious satisfaction the hated carpetbagger rule depart from Louisiana, and hoped for more revenge than that.”

He found a measure of satisfaction when the Supreme Court handed down its decision in 1878. In Hall v. Decuir, the justices held that Pinchback’s anti-discrimination law infringed on Congress’ control of interstate commerce. The court agreed with Leathers’s testimony that segregation was “reasonable” considering that “[t]he colored passengers on my boat are accommodated as well as the white, and are provided with the same bill of fare.” This early federal acceptance of “separate but equal” accommodations helped lay a foundation for the Plessy ruling, as Charles Lofgren explains in his 1987 book The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation.

Following Decuir, the court’s retreat from protections of the rights of Black people proceeded case by case, year by year. Of course, as segregation played out, accommodations for people of color were often far less than equal to those for white people, and they were regularly separated by force, legal and otherwise.

Leathers kept wearing Confederate gray until the federal government had conclusively abandoned any challenge to his supremacy atop his floating palace. According to Wellman, it wasn’t until Democrat Grover Cleveland took the oath as president in 1885 that Leathers declared, “The war is over now,” and ran the stars and stripes up the Natchez flagpole again.

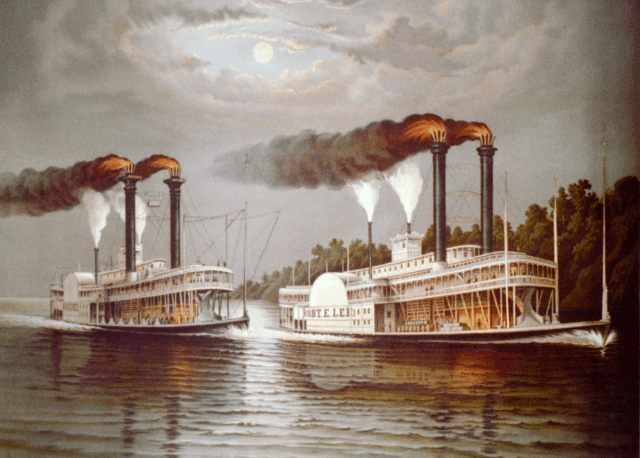

The Great American Steamboat Race of 1870 from New Orleans to St. Louis, Missouri.

On June 4, 1896, a week and a half after the bike accident, Leathers had only fitfully regained consciousness, but the Daily Picayune wrote that there was still a “fair chance for his recovery.” The newspaper’s white editors and readers took Leathers’s stands on behalf of slavery and segregation for granted. More important, as he fought for his life, were all the times he put himself at risk to save others.

The Daily States and Daily Picayune cataloged these acts of valor. Leathers rescued people who fell overboard into the Mississippi, and ferried passengers who were injured on other boats or stricken with yellow fever. One foggy night when he was chugging upstream, he spotted the chimneys of another boat careening toward him and pulled back just in time, avoiding hundreds of casualties by inches.

When he couldn’t prevent a catastrophe, Leathers prevailed seemingly by force of will, as in the 1853 wharf fire when Natchez No. 3 was only a few weeks old. Per the Daily Picayune:

The captain and his wife were on the steamer at the time, and so rapid was the work of the flames that they narrowly escaped cremation, the captain acquitting himself as somewhat of a hero in rescuing his wife and other ladies. One of the captain’s brothers, James, was asleep in the texas of the Natchez at the time and perished in the flames.

In 1868 the steamboat Quitman hit a snag at Morgan’s Landing and cracked open when Leathers tried to move it, taking on a rush of water. Five minutes later it was under the waves, but all eighty-some passengers, including two brides on wedding trips, and every piece of their baggage, had been ushered ashore by the captain.

Natchez No. 7, with stained-glass portraits of Native American warriors in its cabin skylights, struck a reef just below Lake Providence in 1889. Leathers managed to steer it to shallow water, and once again shepherd his passengers to safety. Four days later the New York Times reported:

About dark tonight the chimneys of the steamboat Natchez toppled over, wrenching the boat badly. Her timbers yielded to the strain, and she is going all to pieces. Thus ends the seventh boat having the name of Natchez, and the last of the great side-wheel cotton and passenger carriers of the Lower Mississippi, a boat whose speed and splendor gave her world-wide fame.

Leathers was unscathed, as ever. But at seventy-two, with railroads along the river having long rendered his boats obsolete, he retired rather than build Natchez No. 8. Even then, he “still stood tall and straight . . . a magnificent, towering old Hercules,” Wellman writes. He seemed indomitable until the instant the speeding bike rammed him.

Witnesses described Leathers’s accident on St. Charles to police, but no physical description of the reckless cyclist made it into press reports. Leathers’s celebrity and his relationships with officers of the law made the case a high priority, but the cyclist seemed to vanish as quickly as he’d appeared.

Nineteen days after the hit-and-run, Leathers died. The Daily Picayune reported on June 15, 1896, that every vessel in the port of New Orleans had lowered its flag to half-mast. After failing for nearly three weeks to find the man who killed him, the police appear not to have bothered filing a homicide report when Leathers succumbed. There would be no justice for Captain Tom.

At the funeral, in his home, were “floral offerings strewn in great heaps on the parlor floor around the bier,” the Daily Picayune reported on June 16. Mourners filled the parlors and hall, overflowing into the front gallery and garden, and onto the streets. In his eulogy, Rev. Dr. Benjamin Morgan Palmer, a contemporary of Leathers and fellow successionist, said that his death was “like the death of the century.”

On Leathers’ passing, the Daily-Picayune reflected on June 16: “So thoroughly and fully was his life blended with the pulsating activities of the busy marts of trade that one might say that lives of that kind belong to the public, and are open to the scrutiny and criticism of fellow-men,” and still there was “naught but praise” for him.

Stories abounded of Leathers’s charity and rapport with all classes of people along the river. In his 1887 memoir, the riverboat gambler George Devol recalled taking up a collection to pay for a destitute woman with six children to board the Natchez; hearing of the situation, Leathers put the family in a stateroom at no charge and told Devol to give the woman the money. None of these stories, though, mentioned that his largesse was underwritten by the brutality of cotton plantations.

The Daily Picayune extolled Leathers’s humanitarianism by reprinting on June 14, 1896, a letter of sympathy to his wife from Shedrick Chapman, “an aged colored man, once his slave, later in life his willing servant.” The newspaper assured readers that, to Chapman, “no one was quite as true and fine a man as his quondam master.” The article did not take up the possibility that Chapman endured Leathers’s paternalism in order to earn what it described as “considerable money as porter on the captain’s boats.”

A week after the Plessy ruling, as Leathers waited to cross St. Charles Avenue, he could have seen the approaching tandem bike as an omen of encroaching modernity—cycling was a growing craze in New Orleans at the time. Come what may, he’d done his part to ensure that his century’s racial order, at least, would long outlive him.

An article published June 13, 1896, in the Times-Democrat described Leathers’s unceremonious demise, after surviving decades of derring-do on the river, as “the sarcasm of fate.” It didn’t address the deeper irony that, in the end, he was victimized by—rather than complicit in—arbitrary, unaccountable human violence.

Jordan Hirsch is a writer, editor, and researcher with a specialty in the music and cultural history of New Orleans. He is the editor of ACloserWalkNola.com, the award-winning interactive map of New Orleans music history.