Current Issue

Louisiana as Home

Vietnamese Americans and the fiftieth anniversary of the Fall of Saigon

Published: February 28, 2025

Last Updated: March 3, 2025

Photo by Emily Kask

A worker waters crops at VEGGI Farmers Cooperative in the Versailles neighborhood, which was established to create jobs and grow food in the wake of the BP oil spill.

—E. M. Tran, Daughters of the New Year

Often referred to as Black April, or Tháng Tư Đen among Vietnamese diasporics, April 30, 1975, marks the fall of Saigon and the start of a historic, multi-phase mass migration of Southeast Asian refugees. Since 1975, Louisiana has served as home for tens of thousands of Vietnamese diasporics. The full story of Vietnamese American Louisiana is still coming into relief, but their arrival profoundly reshaped the Gulf Coast. A focus on the New Orleans metro area, particularly New Orleans East, yields important insights, especially since this community has constituted one of the densest Vietnamese American populations in the country.

The initial wave of migration comprised approximately 130,000 Vietnamese fleeing South Vietnam and Cambodia. The US military largely determined the paths that refugees took, routing asylum seekers to refugee camps set up in US military bases across the Pacific and continental United States. Vietnamese refugee journeys thus followed vast US military networks that were also networks of war. During the late 1970s to mid-1990s, another wave of refugee migration transpired when hundreds of thousands of Southeast Asians, including Vietnamese, Chinese Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Laotians, fled in what is known as the “boat people” or “oceanic migrant” exodus. In this wave, asylum seekers pooled resources to pay for dangerous, illegal journeys out of Vietnam in hopes of reaching refugee camps in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. This phase peaked in 1978–79, and those who survived resettled mostly in the United States, Canada, France, and Australia.

Southeast Asian refugees were driven by fears of political persecution and, especially after 1975, realities of severe resource shortages that were direct outcomes of war. Precise numbers of those who fled and died will never be known, but it is estimated that between one-tenth to one-third of oceanic migrants perished. Countless stories exist of refugees who were ignored by foreign ships or pushed back out to sea. Many were subject to pirate attacks, rape, dehydration, starvation, and international neglect.

By 1978, the Vietnamese population in Louisiana numbered over seven thousand, with the majority resettling in the New Orleans metro area.

The Orderly Departure Program’s Humanitarian Operation, conceived in 1979 by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and referred to as “HO” by Vietnamese, was designed to create a legal, safer way for Vietnamese veterans and their families to resettle in countries that had agreed to host them. Over six hundred thousand Vietnamese sought refuge this way. The Amerasian Act of 1982 and Amerasian Homecoming Act of 1987 permitted children fathered in Vietnam by US military personnel to immigrate to America along with some of their immediate family. While thousands of people immigrated through these means, the gendered, racialized, and exclusionary standards built into tests and requirements stirred controversy and numerous lawsuits.

The dominant trope that permeated global media depicting the migration in the 1970s–80s was of a rickety boat overcrowded with Southeast Asians failed by Global South conflict. Such a narrative, which is still prevalent today when asylum seekers are depicted on the news, tended to erase complex refugee lives and imprinted upon global consciousness the idea of the refugee as a dirty, desperate figure in need of humanitarian care. It also minimized the role of US and European powers in creating conditions of forced migration. Recent research has placed more emphasis on refugee perspectives, bringing attention to the layered histories, memories, and politics that refugees carry as they imagine and create refuge in new homes.

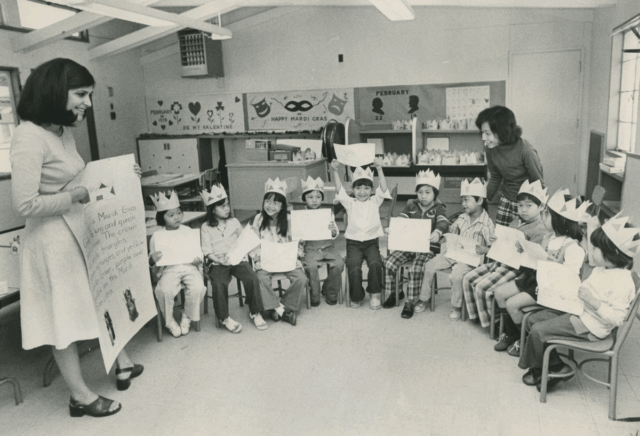

Vietnamese children learning about Mardi Gras kings and queens in an English language class in New Orleans, 1976. Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Mark Cave

The first group of Vietnamese arrived in New Orleans by bus in May 1975. Knowing that many refugees were Catholic, Philip Hannan, Archbishop of New Orleans at the time, dispatched representatives to refugee camps in hopes of recruiting priests. This effort jumpstarted Vietnamese resettlement in New Orleans, which was facilitated by the Archdiocese of New Orleans, Associated Catholic Charities, and the Catholic Conference. Other factors potentially contributed to post-Vietnam War resettlement in the area. Cuban refugees in the city who sympathized with the plights of fellow anticommunist asylum seekers are said to have called upon the archdiocese to help Vietnamese refugees. Although these stories are more anecdotal, they paint a multidimensional picture of how Southeast Asians found a new home in southern Louisiana.

It is worth noting that many Vietnamese Americans in New Orleans East have collectively migrated multiple times. A large number came from the prominent North Vietnamese Catholic villages of Phát Diệm and Bùi Chu. During the First Indochina War (1945-54), these villages were known for their military, social, and political autonomy. After Việt Minh victory over the French at Diện Biên Phủ in 1954, and the consequent division of the State of Vietnam at the 17th parallel, these Catholics migrated together to South Vietnam and reestablished their highly organized subparishes from the North. Collective resettlement in Louisiana enabled yet another transplantation of Vietnamese Catholic community.

By 1978, the Vietnamese population in Louisiana numbered over seven thousand, with the majority resettling in the New Orleans metro area. In New Orleans East, home to vibrant Black communities but often characterized as a social and economic wasteland, significant numbers of Vietnamese refugees were housed in Section 8 apartments. Although much of the population eventually dispersed into single-family homes, thousands of Vietnamese Americans continue to live within a concentrated 1.5-mile radius off Chef Menteur Highway, an area sometimes collectively referred to as “Versailles.” Within the New Orleans metro area, Algiers, Avondale, Bridge City, and Marrero also housed significant numbers of Southeast Asian refugees, as did Iberia, East Baton Rouge, Terrebonne, and Vermilion Parishes. By the 1990s, Vietnamese were the largest Asian American population in Louisiana.

Oral narratives housed at The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC) reveal some key initial employers of Vietnamese refugees, including Schwegmann Brothers Giant Supermarket, the Fairmont Hotel, and Avondale shipyard. Many entered the seafood industry as plant laborers or fishers and shrimpers. The entry of Southeast Asians into the local seafood economy led to tensions between Vietnamese and non-Vietnamese fishers. In Plaquemines Parish, Vietnamese were welcomed by some and subject to racist attacks and vandalism by others, which drove many Vietnamese out. Plaquemines Parish Council president Chalin Perez used orientalist stereotypes to accuse Southeast Asian refugees of disrupting local culture and economy with savage, foreign ways. One fisher complained to the New Orleans Times-Picayune, in a piece published April 22, 1985, that the Vietnamese were “an alien horde that swept into the area and ruined a way of life.” Eventually, some fishers and shrimpers would transition into the nail salon industry, while others became small business owners.

Vietnamese arrival in 1970s Louisiana also resulted in some tensions with Black residents. Black leaders voiced concerns over whether refugee resettlement had displaced or at least compromised Black housing, employment, and social service needs. This led the Urban League of Greater New Orleans (ULGNO) to formally call for the suspension of the Catholic Charities Refugee Program. However, some Black community members emphasized that Vietnamese residents should not be blamed because they were forced to migrate due to histories of empire and war.

A man does his grocery shopping in a Vietnamese market in New Orleans East. Photo by Emily Kask

Two of the most prominent markers of Vietnamese presence in New Orleans since 1975 have been the farms that refugees started cultivating as soon as they arrived and the Mary Queen of Vietnam Church (MQVN). The farms began as small plots in front of individual apartments in New Orleans East and shifted to a large piece of land near Lagoon Maxent that ran behind the levee protecting the neighborhood. Farming has now expanded into the 1.5-acre VEGGI Farmers Cooperative. Over time, Vietnamese Americans have continued to adapt farming practices to meet changing needs, incorporating spray-free practices and aquaponics and soil-based methods. For the community, farms have provided sustenance, a sense of collectivity and self-determination, and a way for members to continue culturally specific agriculture and cooking.

MQVN has served as a spiritual and social anchor for many in the community. The church began as a space of worship in an apartment, graduated to a trailer, then a chapel, and finally evolved into the large MQVN Church located on off Dwyer Boulevard. It has had a national reputation among Vietnamese Americans since Archbishop Hannan officially designated it a Vietnamese parish in 1983. MQVN offers well-attended Masses in Vietnamese, English, and Spanish. Holy Week activities are especially known for giving Vatican protocols a Vietnamese flair, while MQVN’s annual Tết Festival has steadily grown to attract tens of thousands of visitors each year.

Other Vietnamese Catholic parishes can be found throughout the New Orleans metro area, including Our Lady of La Vang Church in Gentilly, St. Joseph Catholic Church in Algiers, and Assumption of Mary in Avondale. Beyond these parishes, the Vietnamese-language Catholic monthly Dân Chúa (People of God), which began publication in New Orleans in 1977, substantially shaped Vietnamese diasporic Catholicism by providing a forum for discussing topics such as spirituality, family separation, human rights, refugee adaptation, and Vietnamese nationalism, history, and culture. Particularly in the early years of resettlement, articles in Dân Chúa interlaced Biblical stories of exodus with the forced migrations of Vietnamese in ways that dignified and sanctified their experiences of statelessness and displacement.

While Vietnamese Catholicism in southern Louisiana has received an incredible amount of attention, significant communities of Vietnamese Buddhists also define the local diaspora. Vietnamese refugees established the first Vietnamese Buddhist community in 1977 in an apartment in the Woodlawn neighborhood of New Orleans. Growth led to the purchase of land on the West Bank and the construction of the Chùa Bồ Đề temple, the first templeone of the first temples in the New Orleans metro area. Vietnamese Buddhists across the Gulf Coast practice a Zen–Pure Land form of Mahayana Buddhism that is notable for its syncretic nature: congregants link multiple strands of Buddhism to other concerns such as Vietnamese American memory and politics and how Buddhist collectivity interfaces with US neoliberal, capitalist, and individualistic values. Gulf Coast temples also extend care and kinship to Vietnamese who do not identify as Buddhist, as well as to non-Vietnamese. Currently, there are five four Vietnamese temples in New Orleans alone, reflecting how the arrival of Vietnamese refugees established a Buddhist foothold where it did not previously exist.

The corner of Vanchu Drive and My-Viet Drive, an indication of the prevalence of Vietnamese presence and culture in New Orleans East. Photo by Emily Kask

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall along the Gulf Coast as a category 3 storm. At the time, about five hundred Vietnamese Americans remained in eastern New Orleans. When the storm subsided, Father Vien Nguyen, former pastor of MQVN, helped to pick up survivors in boats. But the water began to rise. The Intracoastal Waterway levees protecting New Orleans East breached, resulting in six to eight feet of flooding in New Orleans East.

When the Bring New Orleans Back Commission unveiled its redevelopment plans, it deemed New Orleans East uninhabitable. Cynthia Willard-Lewis, New Orleans City Council member at the time, states in S. Leo Chiang’s documentary A Village Called Versailles that the city basically told the district’s Vietnamese American and Black residents: “We don’t want you back.” Father Vien lamented, “The map ended. Right on our border. That’s exactly how we felt all along. We were never on the map.” The ongoing neglect and marginalization of New Orleans East’s residents was again on display in February 2006, when Mayor Ray Nagin used emergency powers to grant Waste Management a permit to operate the Chef Menteur landfill near Versailles as a dumpsite for toxic Katrina trash. This caused grave concerns among Vietnamese American and Black residents over long-term health impacts.

“The map ended. Right on our border. That’s exactly how we felt all along. We were never on the map.”

The response to these catastrophes saw a surge in Vietnamese American grassroots activism and civic engagement as Vietnamese Americans organized to survive and rebuild. This resulted in the eventual inclusion of New Orleans East in redevelopment plans. By 2007, their rate of return reached 90 percent, according to Mark J. VanLandingham in Weathering Katrina: Culture and Recovery among Vietnamese Americans (2017) and Karen J. Leong, Christopher A. Airriess, Wei Li, Angela Chia-Chen Chen, and Verna M. Keith in “Resilient History and the Rebuilding of a Community: The Vietnamese American Community in New Orleans East,” published in Journal of American History in 2007. MQVN Community Development Corporation and Vietnamese American Young Leaders Association (VAYLA), two nonprofits that emerged after the hurricane, filed a lawsuit against Waste Management of Louisiana in consultation with environmental attorney Joel Waltzer, alleging that the landfill authorized by Nagin constituted an “open dump” in violation of federal law. The community mobilized across generations and with Black neighbors to protest at City Hall and the landfill site. A court order finally closed the landfill on August 15, 2006, although numerous landfills and illegal dumpsites in the area remain.

Today, numerous ground-up initiatives attest to the Vietnamese American community’s commitment to crafting home in Louisiana, not only for themselves but for other marginalized communities as well. Even as Vietnamese Americans celebrate the community’s perseverance, New Orleans East is still underserved and neglected, experiencing environmental racism, food insecurity, and transportation and housing injustice. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill on April 20, 2010, resulted in tainted food sources, complicated claims processes that many Vietnamese-language speakers could not maneuver, and destroyed livelihoods for those whose work ties to the fishing industry. Organizations such as MQVN Community Development Corporation, Sông Community Development Corporation, VAYLA, VEGGI, Vietnamese Initiatives in Economic Training, and Coastal Communities Consulting help Southeast Asian Americans as well as other locals confront ongoing systemic injustices. They provide services such as employment training, translation, and workshops on agriculture and hurricane preparedness to help vulnerable communities survive in unpredictable times. Grassroots activities in New Orleans East has also fueled Vietnamese American visibility in public office. Republican Joseph Cao, who became the first Vietnamese American to serve in the US Congress in 2009, and Democrat Cyndi Nguyen, who became the first Vietnamese American woman to serve New Orleans City Council in 2018, both trace the start of their political careers to their work in eastern New Orleans.

Women making pork bao buns by hand at James Beard Award-winning Dong Phuong Bakery in New Orleans East. Photo by Emily Kask

Vietnamese American foodways, scholarship, literature, and art flourish in theregion today. Vietnamese restaurant mainstays include Danny’s Seafood, Original Cajun Seafood, Pho Tau Bay, and Tan Dinh. Produce and bread from Vietnamese American merchants in New Orleans East source many of the area’s restaurants; Dong Phuong restaurant and bakery received a 2018 James Beard America’s Classics award, and impassioned debates erupt every Carnival season about whether or not its king cake is the best in the city. Chefs Nini Nguyen and Anh Luu have taken their New Orleans background to prominence on the national stage. Writers including E. M. Tran and Eric Nguyen reimagine Vietnamese American and southern American literature by highlighting Vietnamese characters and storyworlds in New Orleans. Prospect.6, the international contemporary art triennial currently on view in exhibitions throughout New Orleans, features a number of Vietnamese and Vietnamese American artists whose works invoke Louisiana in provocative ways, including Christian Việt Đinh, Tuan Mami, Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, Dylan Trần, and Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần. Other prominent contemporary artists who are based in New Orleans or whose work draws from Louisiana include Marion Hoàng Ngọc Hill, An-My Lê, and Hương Ngô.

To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon, institutions such as Tulane University, THNOC, and the Ogden Museum have curated events and exhibitions that showcase the richness of Vietnamese American culture and history. New Orleans–based Vietnamese American organization Journey of Resilience is partnering with some of these projects and developing its own programming to center community perspectives in the city’s commemoration of the fall of Saigon. As we remember the end of the Vietnam War and consider its impacts on Southeast Asia and its diasporas, it is essential that the stories we tell about Louisiana do justice to the worlds that Vietnamese Americans have built.

Marguerite Nguyen is a current professor at Wesleyan University, and the author of America’s Vietnam: The Longue Durée of U.S. Literature and Empire (Temple University Press, 2018) and co-editor of Refugee Cultures: Forty Years after the Vietnam War (MELUS, 2016). Her research is in the dynamics of race, migration, environment, and narrative form in Southeast Asian American cultures of Louisiana.

Editor’s note: Across the essay, Nguyen uses “Vietnamese Americans” to broadly denote a fluid identity and ethnic category that is not tied to legal status. It includes those across citizen and non-citizen statuses. Nguyen uses “Vietnamese diasporics” when referring to Vietnamese who migrated, as this term can carry a stricter definition that excludes those born in the US.