Current Issue

“Easier to Sing Than to Talk”

Excerpt from You Are My Sunshine: Jimmie Davis and the Biography of a Song

Published: February 28, 2025

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

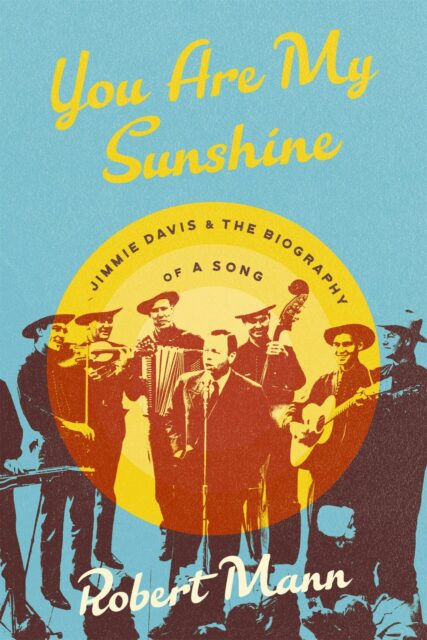

From the Harry Pennington Jr. Photography Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Jimmie Davis and his campaign band perform in Louisiana during the 1943–1944 governor’s race.

In You Are My Sunshine, Robert Mann weaves together the birth of country music, Louisiana political history, World War II, and the American Civil Rights Movement to produce a compelling biography of one of the world’s most popular musical compositions. Despite its simple, sweet melody and lyrics, this song’s story holds the weight of history within its chords.

Robert P. Letcher, a Kentucky congressman and friend to President John Quincy Adams, was known for his wry wit and fiddle-playing. “Often in the heat of angry and fierce debate,” Adams observed, “he throws in a joke, which turns it all to good humor.” Letcher used music when he ran for Kentucky governor in 1840 by entertaining crowds with his fiddle and taking song requests from audience members at gatherings. He won the election. Another accomplished fiddler, George M. Bibb, served as a US senator from Kentucky and, later, as US treasury secretary from 1844 to 1845. When serving as chief justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals in the late 1820s, Bibb solidified political alliances by playing for legislative dances. “He kept the lawmakers in a giddier whirl with his fiddle bow than he ever did with decisions from the high bench,” one historian noted. Fiddler Tom Watson played songs like “Mississippi Sawyer” and “Buffalo Gals” on the stump in his successful 1882 Georgia US House race.

Robert P. Letcher, a Kentucky congressman and friend to President John Quincy Adams, was known for his wry wit and fiddle-playing. “Often in the heat of angry and fierce debate,” Adams observed, “he throws in a joke, which turns it all to good humor.” Letcher used music when he ran for Kentucky governor in 1840 by entertaining crowds with his fiddle and taking song requests from audience members at gatherings. He won the election. Another accomplished fiddler, George M. Bibb, served as a US senator from Kentucky and, later, as US treasury secretary from 1844 to 1845. When serving as chief justice of the Kentucky Court of Appeals in the late 1820s, Bibb solidified political alliances by playing for legislative dances. “He kept the lawmakers in a giddier whirl with his fiddle bow than he ever did with decisions from the high bench,” one historian noted. Fiddler Tom Watson played songs like “Mississippi Sawyer” and “Buffalo Gals” on the stump in his successful 1882 Georgia US House race.

Huey Long campaigned for Louisiana governor in 1928 with the Leake County Revelers, a popular string band imported from Mississippi to entertain crowds at rallies in rural areas. Gene Austin, a popular singer from Yellow Pine, Louisiana, also performed at some Long rallies. Across the Sabine River, folksy Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel of Fort Worth won the governorship of Texas in 1938 on the popularity of his Western swing band, Pat O’Daniel and His Hillbilly Boys. His statewide radio show and the band had first been vehicles to promote his company’s Hillbilly Flour. The company’s bags featured a lone billy goat over the words to a poem that O’Daniel said he had composed: “Hillbilly music on the air, Hillbilly Flour everywhere. It tickles your feet, it tickles your tongue. Wherever you go, its praises are sung.” The band’s popularity (the original unit included Western swing pioneers Bob Wills and Milton Brown) soon lured O’Daniel into politics. “O’Daniel was known in thousands of Texas homes,” Bill Malone and Tracey Laird wrote, “where he was perceived as an almost fatherly presence and a quasi-populist champion of common people.” He won the race.

In Shreveport, a shrewd entertainer and emerging politician like Jimmie Davis surely noticed how O’Daniel exploited the fame his band and statewide radio show generated, as well as how he first used music to promote flour and then his candidacy. In quick succession, O’Daniel had won landslide victories for governor in 1938 and 1940 and a special election for US senator in 1941, beating then-congressman Lyndon Johnson. He won a full term in the Senate the following year.

In Baton Rouge in January 1943, Davis took his seat on the state’s Public Service Commission, explaining to reporters that his method of stumping was preferable to the traditional mode of waging a campaign. “I’ll tell you something about my campaigning,” he told a reporter. “It wasn’t long before I found out that people just don’t want to hear some long-winded speech. They have a much better time hearing a few words and then listening to some band music and a song or two. And I don’t mind saying I find it a whole lot easier to sing than to talk.” It was also the case that Davis was uninterested in the finer details of public policy. He once admitted that after leaving LSU, he rarely read a book, and he got much of his information by flipping through newspapers and magazines. Like many successful politicians in every era, he was far more interested in the performance part of the business and less attracted to governing and policy formulation.

What Davis had done—singing his way into two public offices—was fine for one of the more rural regions of the state. But could a quick speech, followed by some spirited hillbilly music, work in a governor’s race in Louisiana as it had in Kentucky, Georgia, and Texas? By September 1943, when Davis announced his candidacy for Louisiana governor, he was ready to find out.

Excerpt from:

You Are My Sunshine: Jimmie Davis and the Biography of a Song by Robert Mann

$29.95; 216 pp.

Louisiana State University Press (February 2025)