Spring 2020

A Conversation with Terence Blanchard

Melissa A. Weber sits down with the 2020 Humanist of the Year

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

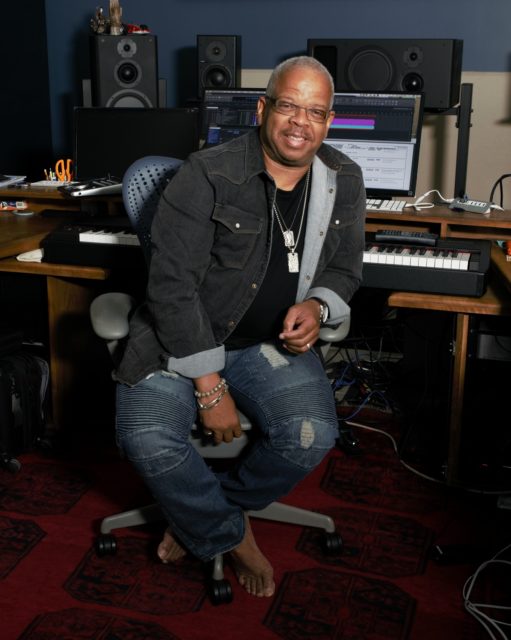

Photo by Eric Waters

Terence Blanchard at home.

In 2019, Blanchard completed his second opera, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, making him the first African American composer to be featured at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. He also received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score for Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, and he completed the score for Harriet—the latest in the list of more than fifty films Blanchard has scored, including Kevin Costner’s Black or White, George Lucas’s Red Tails, and Oprah Winfrey’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.

I spoke with Blanchard about his multidisciplinary and multifaceted approach to art, which is centered by his devotion to the human condition, to tradition, and to evolution. And in the true Blanchard trajectory, there are more things to come for the 2020 LEH Humanist of the Year.

Melissa Weber: You have no boundaries, in terms of your artistry and the projects that you do. Is there anything you want to do that you have not done yet?

Terence Blanchard: There are things that I want to do with my electric band [The E-Collective]. We put the band together to inspire young kids who may not want to play jazz. We wanted them to at least play instruments on a high level. Because it kind of felt like that was getting lost in the whole era of kids playing [electronic] loops. And there’s nothing wrong with that—we do that—but [you have to] understand where that comes from . . . and how you can manipulate that. So with this band, we’re trying to bring together all of those elements. We want to do something creative and interesting, but at the same time danceable.

Karen Slack as Billie and Michael Redding as Uncle Paul with the young Blow brothers (L to R: Jayden Denis, Nathaniel Mahone, Najee Coleman, Rhadi Smith, and Jeremy Deins) in the world premiere of Terence Blanchard and Kasi Lemmons’ “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.” Photo by Eric Woolsey, Opera Theater of St. Louis

MW: How did you begin composing for operas?

TB: [Music educator] Jonathan Bloom and myself, we talk about it all the time because a lot of people don’t know it. His mom and my dad used to sing together. And they studied opera. In New Orleans when you talk about musical lineages, you talk about the jazz . . .. But our parents were part of this whole crew of African Americans who loved classical music. So I heard a lot of operatic music in my house growing up. But I never thought about writing opera. Fast forward years later, the Opera Theatre of St. Louis . . . wanted to do a jazz opera for children and [wondered] who would be the composer to get for that? And Gene Dobbs Bradford [of Jazz St. Louis] said, “I think Terence Blanchard would be the perfect guy.” Well, when they contacted me, in the midst of them discussing this whole thing, they decided not to make it a children’s opera but an opera for the main stage.

My dad had passed . . . maybe fifteen or twenty years by that time. And it was weird, that moment of life [going] full circle, you know? And when you start to believe, if you still have the belief in faith—because I had no aspirations to go on that road [with opera], then all of a sudden, here’s my life making this turn back to where I began, which was really bizarre for me. And once I got into it, I started meeting all of these African American singers and performers who grew up the way I did. Grew up in the church, grew up with this [opera] music, and it was a big part of their life. I was the one that ran away from it, because I ran away being a jazz musician. The guy who . . . played in my church, his name is Osceola Blanchet. Bloom said he was probably one of the most revolutionary dudes in New Orleans. Because he used to teach at [McDonogh] 35, and he made it his mission to teach Black kids opera. And he had a group called the Osceola Five. And my dad was a part of that group. These Black men used to go to his house every Wednesday night to rehearse and sing operatic and classical music. The reason why I’m bringing these names up is because it’s like my entire existence at that point, I was surrounded by these minds. I was the one breaking out because I heard Clifford Brown, and I heard Miles Davis, and all of that stuff.

So when they asked me to do [opera], I . . .was intrigued, but I was scared. But I’ve never been one to shy away from anything outside of my comfort zone. I always look at challenges as a means to grow. The wild part about it is that it kept bringing me back to my roots. In the midst of me doing this stuff, all of a sudden I hear my dad singing these melody lines. I hear all of these men, and it’s like their spirits were sitting around with me at the piano singing these lines. And it was a really, really bizarre experience. Because I always wanted to be the hip guy, who’s going to be the hip, cutting-edge jazz musician, not sitting around writing opera, you know?

When we did the first one, when I met Denyce Graves, Aubrey Allicock, and Arthur Woodley—those are the three principles in Champion, the first opera—I can’t explain to you, the moment when they started to sing, how emotional I was.

It’s been a beautiful journey. My jazz background, my film background, everything comes into play when I’m doing opera, and I can’t talk enough about it because it was so unexpected . . . but it’s been blowing me away.

We . . . didn’t really understand what New Orleans was truly offering until [we] left, because you kind of took it for granted. We thought every place was like New Orleans.

MW: What motivates you as an artist?

TB: It comes down to what music did for me since I was a kid. Growing up in New Orleans, you can’t walk down the street on any given day without hearing a marching band or some drummers play. I remember being downtown with my mom shopping, and you would pass by certain areas, especially over there by Congo Square, and you would hear drummers out there playing. It just used to intrigue me, because I knew that feeling that I would get from that. And I think those are the things that inspire me. And truth be told, man, I’m trying to heal myself too. We all have our demons, we all have our issues that we’re trying to face. Art Blakey used to say, “Music is the only place I can go to be who I really am.” And I really believe that.

Because when you’re facing the struggles of society and all those other things . . . it’s rough. Raising kids, now having a grandkid that’s a young African American male . . . There are things that you worry about and you struggle with and you don’t want them to go through.

My son was falsely arrested by the cops. Mistaken identity. Well, not even mistaken identity. This guy came home while my son was walking to school, and a dude ran out the back of the house and the woman said, “Oh, I think we were robbed.” And the husband goes, “Well, what did he look like?” “A black guy with dreads.” And then he walked around and saw my son walking to school, going to Dillard [University]. Called the police. Police showed up, seven cars. They . . . brought my son in handcuffs, put him in the car, brought him over to the woman. The woman said, “Yeah, that’s him.” And if it wasn’t for one of the cops who lived in the house behind mine that I grew up in . . . he was on the scene. And he said, “I know this kid and this kid didn’t break in nobody’s house.” So they went to re-interview the woman, and next thing you know the woman’s story started to break down. So they realized she was lying.

And I’m in Europe. I’m in between flights, trying to find out what’s going on, and just as easily as that, my son could have been gone, could’ve been in the system because of somebody else’s lie. And those are fears that you have. So I’m trying to heal myself in terms of my own frustrations with things that are going on and, in hopes of me healing myself, will hopefully heal other people as well.

MW: What made you want to take a break from New Orleans to go to New York [in the 1980s]?

TB: I’m glad you asked that question. I think most of us probably went through this . . . guys in my generation. We . . . didn’t really understand what New Orleans was truly offering until [we] left, because you kind of took it for granted. We thought every place was like New Orleans. And it wasn’t until you left, and you got up to New York, and you go, uhhh.

But New York was the Mecca. New York was the place that if you wanted to be a jazz musician, you had to go there. That’s where all of the musicians were. That was the place that I had to be. And I’m glad that I did it, because it . . . opened me up to so many different things, because there were so many different types of people there, so many different types of musicians. As a result of playing with Art Blakey I started traveling the world, started seeing other things. And the wild part about it was I saw how it all related to New Orleans. It made me appreciate Louis Armstrong in a way that I couldn’t appreciate before. It made me appreciate all of the . . . trumpet players that had come up in . . . this long lineage of musicians here that were doing great things. And I saw how that music had an impact on what we call the modern movement of jazz.

MW: Also, while you were in New York, is that how you met Spike Lee and got involved in film scoring?

TB: I was a part of that from the music side. I got in touch with Spike because of a jazz musician. His name was Harold Vick. He was a friend of Bill Lee [bassist and father of Spike] and he contracted the musicians for the sessions, so for School Daze, Do the Right Thing, I played on all of those, but just as a session guy.

[Spike and I] became friends, and then he asked me to do [the score for] Jungle Fever. The whole film-scoring thing came totally by accident. Because we were doing Mo’ Better Blues, we were taking a break, and I was playing something on the piano. He said, “What is that?” And I said, “Well, it’s a song that I was writing for my first solo project for Columbia Records.” It was called “Sing Soweto.” And he said, “I want to use it just as a solo trumpet thing.” So we recorded it, just a solo trumpet piece. Next thing you know, he asked me if I could write a string arrangement for it. He said, “Can you write for strings?” I said, “Yeah.” I lied.The first thing I did, I called [New Orleans–born composer] Roger Dickerson, who has always been like my musical family. And Roger told me, “Trust your training.” See, Roger is part of this other coalition of Black composers that nobody knows about. This dude studied in Vienna, and he was a disciple of another great Black composer named Howard Swanson. He’s a colleague of another great Black composer, Hale Smith. As a matter of fact, when I [lived in New York], Roger told me to go study with Hale in Connecticut. So there was this connection of great composers that kind of took me under their wing.

Everybody thinks I just fall out of the sky doing this stuff. These guys taught me everything I know. But after I wrote [the string arrangement], I came back with the music, and I handed it to Spike’s dad. Spike’s dad goes, “You wrote it, you conduct it.”

He said, “Can you write for strings?” I said, “Yeah.” I lied.

MW: Back to your E-Collective band, you said you’re planning to continue in the direction with fusion and less traditional sounds. How would you classify your new music?

TB: We really don’t know, and we embrace that part of it. Because I think sometimes when you classify something, you find yourself with an obligation to be that. Art Blakey always used to say, “Man, I’ll leave that for the historians.” He said, “That’s not for me. What’s for me is to create.”

[As] an artist, it’s your obligation to stay curious and constantly grow. That’s the most important thing for me. I remember having this conversation with Wayne [Shorter]. He doesn’t talk about music in regard [to classifications]. He just talks about creating sounds and creating ideas. So that’s really how I see it now.Wayne [also] said, “Jazz means I dare you.” And that’s true. I want to create that music that makes people go, “What is that?” I don’t want you to be able to pin it down because I feel like if you can pin it down, I’m not doing my job.

MW: That speaks to New Orleans music.

TB: And in New Orleans music right now, there’s one person that I really feel is doing something incredible. And that’s Tarriona “Tank” Ball [of Tank & the Bangas]. We just did a show together at Carnegie Hall. I told her, “One of the things that I love about you is that . . . what you are doing is making people reevaluate what New Orleans music is.”

We’re supposed to evolve. Do I love my tradition, my hometown? Hell yes. There’s nothing like it. But . . . the thing that makes that music so powerful is that it was born out of pain and it was born out of a need to express something. It was born out of a need to connect to the creator. And there’s a certain kind of passion and energy behind that . . .. Because when you’re really about that connection, it evolves anyway. Because then it’s really about you . . . [and] what you’re trying to say. And that’s the most important thing, to recognize where we come from and recognize our lineage and our history. But in order to truly pay homage to that is to constantly move forward and be ourselves.

Melissa A. Weber is a curator of Tulane University Special Collections at the Hogan Jazz Archive of Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, New Orleans.