Current Issue

A Lavender World

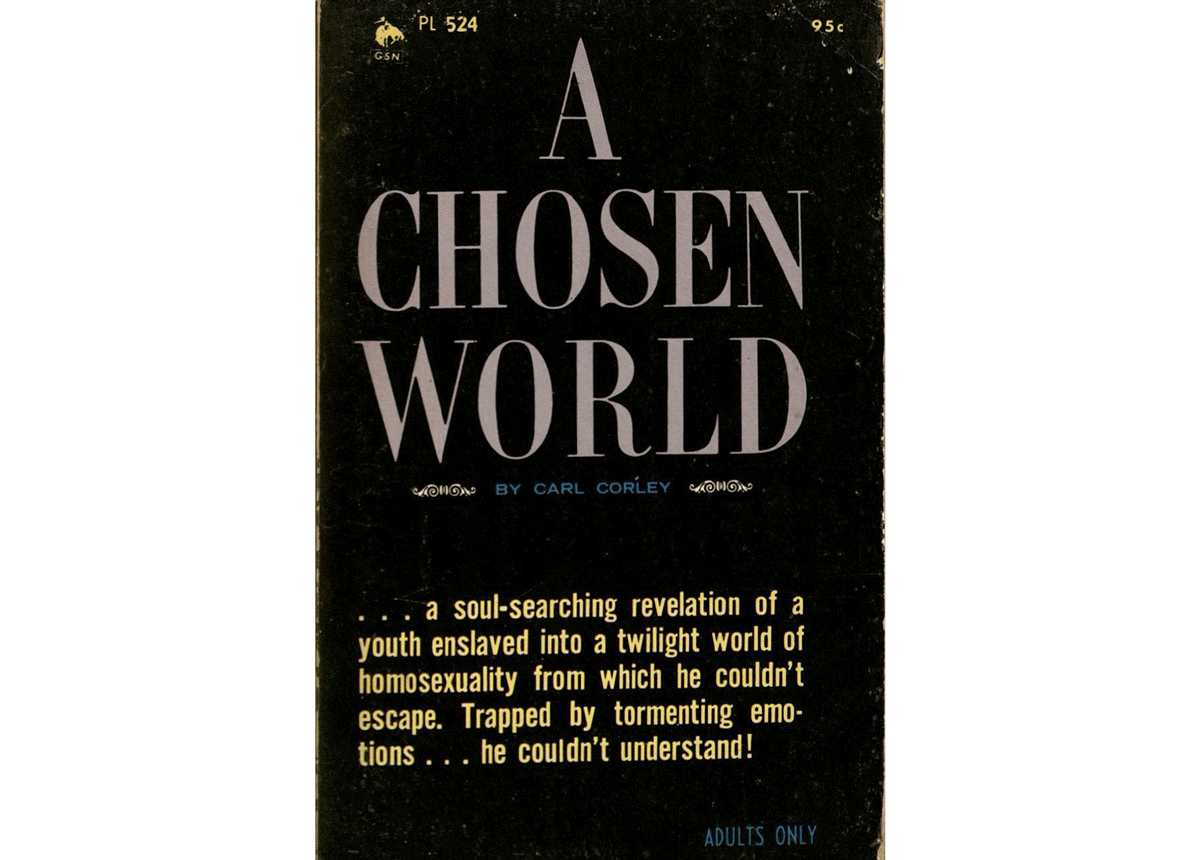

Carl Corley’s A Chosen World is his most autobiographical book

Published: August 29, 2025

Last Updated: August 29, 2025

Pad Library (1966)

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of Carl Corley’s brief and bewildering writing career is that his own name appears on the covers of his books. Only one, perhaps two other authors who shared a genre with Corley had the pluck—some might say gall—to publish under their legal names. Corley specialized in gay pulp fiction, publishing twenty-two cheap, small-press paperbacks between 1966 and 1971, their beefcake covers and suggestive titles hinting at the then, and perhaps still lingering today, taboo content within.

One of the first published authors of gay pulp, Corley wrote at a time when homophobic public harassment, laws criminalizing same-sex behavior, and specious arrests were the norm across the nation. His books, with their titillating covers popping with his own muscle-man artwork, frequently drew from his own life as a gay man in the Deep South. Improbably, he published (with his legal name, it bears repeating, openly emblazoned on the covers) while employed by the Louisiana state government.

Corley’s first and most autobiographical work, A Chosen World, closely follows the contours of the author’s life starting in 1935. The protagonist Rex Polo is, like so many teenagers, a bit lost. Growing up in Rankin County, Mississippi—just like the author—he’s athletic, artistic, and doesn’t know where he fits in, until he meets Norman. They kiss and “in that instant,” Rex says, “I changed. Fate abrooded my world. Whatever I had been before, whatever I had hoped to become, I would never be again, would never become.”

Their relationship quickly turns sexual. Corley churns out filigreed lines typical of any mainstream romance novel. “We met, drawn by this strange arch-angel of desire, and drank from love’s draught, fulfilling quickly, as an elf eating lilies, sharp toothed and cautious,” he writes. “He was an altar, and I was the sacrifice on the altar.”

“Where the other Marines had only one enemy, the Japanese . . . I had two.”

Reading any of Corley’s novels, especially his debut, can feel like entering the author’s fever dream. They are short, blue, sloppily plotted, and published, as in the case of A Chosen World by Pad Library out of Agoura Hills, California, with little to no time for editing or proofreading.

Though the books are cheaply made, they hold value. “Pulps were interpreted as an important cultural site of community-building, one of the only places where queer people could see versions of themselves, even if those representations were sometimes negative,” Hannah Givens writes in a 2017 University of West Georgia thesis on Corley’s life and work. Books like his “helped pave the way for later queer organizing, activism, and visibility” by capturing the lives of gay individuals engaged in sexual relationships.

The sex scenes in A Chosen World, which are numerous, graphic, and often graphically violent, are both tedious and necessary in advancing the plot. For Rex, another lover soon enters the picture: Maurice, a dark-lit soul who “looked like a pirate walking the plank.” Instead of fighting over their shared interest, Norman and Maurice gang up on him, sending Rex to a lengthy bed-ridden convalescence.

He has better luck with Luther, a sweet partner who is unafraid to confess his love. But Luther’s parents find out about their relationship and force Luther to join the Navy. Heartsick, Rex joins the Marines and is sent to bootcamp in San Diego. One week later, the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor.

Shipped out to the Pacific, he works as an intelligence officer making hasty sketches of enemy positions and armaments in some of the war’s most brutal battle zones: Guadalcanal, Guam, Iwo Jima. He finds succor in relationships with fellow soldiers but also frequently experiences physical and sexual abuse at the hands of his brothers-in-arms. “Where the other Marines had only one enemy, the Japanese,” Corley writes, “I had two.”

In remembrance of the pain they afflicted, Rex self-tattoos, with needle and ink, a star under his right eye. “A holy medal,” he calls it, “reminding me that the crime was not mine—but theirs. I wear it proudly.” That detail, like much of A Chosen World, is drawn from Corley’s life. “Fact and fiction regularly blurred in Corley’s life work,” his biographer John Howard writes in Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (1999). After serving in the Pacific War, Corley sported a blue star on his right cheek for the rest of his life.

Back home in Mississippi, Rex begins selling painted pinup art—one hundred bucks for a full-page spread—to male physique magazines, fitness and health titles then popular among budding bodybuilders and (because of their unquestionably erotic imagery) gay men. The trajectory again parallels Corley’s. “One of my ambitions [was] to be the greatest male physique artist of all,” he told Howard.

Rex also earns income by producing tourist maps and other official publications for the states of Mississippi and Louisiana. The book ends in Baton Rouge, where Rex more openly finds his place in what he calls the “lavender world,” his chosen world, centered around the Looking Glass Lounge, a gay bar inspired by a real-life, once-popular, long-shuttered establishment in downtown Baton Rouge known as the Mirror Lounge.

A Chosen World was published in 1966, five years after Corley moved to Baton Rouge to work for the Louisiana Department of Transportation, where he produced a prolific amount of printed ephemera for the state for two decades. Coworkers remembered the Ford Pinto Corley drove, covered in his paintings of beefcake-y men. On the side, he continued to write gay pulp while working on other illustrated projects, including an illustrated biography of Jesus (The Agony of Christ, published in 1967) and two cartoon-style serials for the Eunice News. One cartoon depicted Biblical tales; the other depicted stories from Louisiana history, starring a Cajun-meets-Tarzan character named Pe’pa Paree, who roams the swamps and prairies of Acadiana looking very buff and often very nude.

In 1981, five months before Corley’s scheduled retirement at the age of 59, the State of Louisiana fired him, likely, his biographers theorize, motivated by homophobia. He relocated with his partner to Zachary, Louisiana, opened an art gallery, tended his garden, and continued to write and illustrate. Hard copies of his books are difficult to source, but most have been digitized at carlcorley.com. He died in 2016, at 94 years old, three months after losing his home in that summer’s Amite River floods.

Buried back home in Rankin County, Mississippi, Carl Corley’s tombstone is inscribed with Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem “First Fig”—perhaps particularly fitting for a man who led such a richly varied life and career: “My candle burns at both ends; / It will not last the night; / But ah, my foes, / and oh, my friends— / It gives a lovely light.”

Rien Fertel has been writing the Lost Lit column for eight years.