All’s Fair in Love and War

French Quarter Sicilians and Italian POWs

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: February 13, 2025

Linda DiMarzio Massicot

Brides and grooms, left to right: Mary Messina Pezzana and Antonio Pezzana, Dorothy Messina DiMarzio and Ermanno DiMarzio.

Giovanni DiStefano, a spry ninety-four-year-old, was the star attraction that day. Legally blind but still with a twinkle in his eye, he took the microphone and told his story. “It started with a dance at the Jackson Barracks,” he said in perfect English with a soft Italian accent. “My friend Larry was interested in a girl, but he didn’t speak Sicilian. I could speak Sicilian, French, and Italian, so I would translate. There were seven sisters, so I figured there would be at least one for me.” He was right.

After the Allies defeated the Axis forces in North Africa in May of 1943, 51,000 Italians and 380,000 Germans were brought to the United States as POWs. Jackson Barracks in New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward housed about 1,000 Italian POWs, most of whom arrived in 1944 from military bases elsewhere in the country. Other Italians were held at Camp Plauche in Harahan. Many more Germans were held at dozens of camps around Louisiana, mainly near rice, sugar cane, and cotton fields, where they were put to work. Germans were also held at Camp Leroy Johnson on the New Orleans lakefront.

In 1944, Dorothy Messina was living with her parents in a Sicilian immigrant enclave of the lower French Quarter. In an interview with her daughter Linda (DiMarzio) Massicot, she recalled the first time she saw her future husband Ermanno DiMarzio at Jackson Barracks. “I fell in love with his ears,” she said. “He was sitting on a bench, reading the paper with a cigarette in his hand and turning the pages. He didn’t know I had my eye on him. Then he turned around and flipped the cigarette down. As we passed by there, he looked at me and I looked at him.”

One of ten children, Ermanno had been studying accounting at the University of Rome when he was called up for the war, along with his eight brothers. He was a lieutenant in the Italian Air Force when he was captured in Tunisia in 1943.

DiStefano, who grew up in Italian colonial territory in Tunisia and joined the Italian army there, recalled his own capture. “One English soldier stopped our trucks—there were forty of us and one man disarmed us.” Mussolini had left his men—most of whom were conscripts—in the desert without food, water, or ammunition. Some of them even surrendered to unarmed medics. Most of the Italians were overjoyed to be captured, DiStefano said, and even more excited when they found themselves on a ship to America.

New Orleans chef Joe Faroldi, owner of Lakeview Burgers and Seafood, is the son of a Jackson Barracks POW and a French Quarter Sicilian woman. Faroldi recalls his father telling him, “We were supposed to be the ‘fighting elite,’ but we had no bullets. We were starving.” Faroldi’s father was twenty years old when he was captured.

After Italy surrendered in September of 1943 and switched sides in the war, the United States had a dilemma. The Italian POWs did not really pose a threat, but the Geneva Convention prevented their release, and prisoners of war could not be sent home to active combat zones, which Italy was. In March 1944, most of the Italian POWs signed a loyalty oath and joined Italian Service Units, which assisted the American military in a time of severe labor shortages on the home front. They dressed in the same uniforms as the US soldiers, but with a green oval patch on their sleeves that said “ITALY.”

The presence of the POWs created an interesting dilemma for the French Quarter Sicilian Americans. On one hand, these POWs were paesani—countrymen. Most had been conscripted or joined Mussolini’s army with little enthusiasm, often to escape grinding poverty. Few of them had any allegiance to the fascists the Allies were fighting to defeat.

“My friend Larry was interested in a girl, but he didn’t speak Sicilian. I could speak Sicilian, French, and Italian, so I would translate. There were seven sisters, so I figured there would be at least one for me.”

On the other hand, most Italian Americans were fiercely loyal to their adopted country and had been uncomfortable about Italy’s role as an enemy combatant. They saw the Japanese Americans—and even some of their own—being herded into internment camps early in the war. In spite of the presence of high-profile Italians in American civic life (including New Orleans’s then mayor Robert Maestri), some were worried that fraternizing with the POWs might call their patriotism into question.

Indeed, Andrew J. Higgins, whose shallow-draft “Higgins boats” helped the Allies take the beaches of Normandy and elsewhere in the European and Pacific theaters, was a vocal opponent of the “coddling” of German and Italian POWs. Higgins employed an integrated workforce of about twenty thousand men and women at his New Orleans–area factories at the height of the war. In August of 1944 he wrote to Louisiana’s congressional delegation about his concerns over the treatment of POWs. “Right here in New Orleans, Italian prisoners have the freedom of the streets, and are even entertained at bathing parties on Lake Pontchartrain,” Higgins wrote. “All of this coddling of our enemies is excused by the statement that it is required by the laws of war, and the requirements of the Geneva Convention. Is there anyone in this country foolish enough to believe that the Germans are showing our men, officers or privates, like consideration?”

The irony of the gentle treatment of these POWs was also not lost on the families of Black soldiers returning to the indignities and violence of the Jim Crow South after bravely serving their country overseas. While over a million African Americans served in the US armed forces, fighting for democracy and against Hitler’s racist atrocities, Black military policeman stationed in the South could not enter restaurants where the POWs they were guarding were allowed to eat.

In spite of these conflicting views, in New Orleans, Boston, New York, and other cities with large Italian populations, the Army worked through churches and businesses to connect the POWs with local families, ostensibly to keep them from causing trouble out of restlessness. The Italian American visitors were a great comfort to the POWs, so far from home, speaking their language and bringing them familiar food. The Army eventually allowed the Italian POWs certain freedoms and sent military escorts with them to dinners at family homes, Mass at St. Louis Cathedral, and other social events away from the barracks.

With most of the young American men off at war, the daughters of local Sicilian American families welcomed the young Italian soldiers as new dance partners and friends. “People used to joke that the girls went to the barracks for ‘husband shopping,’” Joe Faroldi remembers hearing from his parents. The Army even held dances at Jackson Barracks, some of them organized by Central Grocery’s Lupo and DeMajo families.

At ninety-two, Hammond resident Marguerite (Graffagnini) Maranto remembered the event at which she met her future husband like it was yesterday. “I was the secretary of the Ladies Auxiliary Club at the Italian Hall on Esplanade,” she said in a 2019 interview. “A military man came over and wanted me to get some Italian girls so they could dance with the boys, the prisoners of war, just like the USO. I called around and we got fifty girls. They came to get us and here we were, jumping on the truck—that was hard to do—we were all dressed up. Then we went [to the barracks] and there were all these men!”

As the war dragged on, the women became regular visitors to Jackson Barracks on Sunday afternoons—always with a chaperone. On one of those visits, Marguerite met Mario Maranto from Padua, Italy, “where Saint Anthony was from.” He was twenty, she was seventeen. He spoke no English and she did not speak Italian, so her mother served as an interpreter for them as they courted.“He was it,” she said. After knowing each other for about a year, “he told my mother he wanted to marry me and asked her to buy a ring for him.” Mario proposed to her in the day room at Jackson Barracks, with her mother translating.

Ermanno DiMarzio and fellow POW Antonio Pezzana got to know Dorothy Messina and her sister Mary. Dorothy worked as a secretary at the New Orleans Port of Embarkation. Ermanno was an interpreter and would often come into the port office on official business. Forbidden to speak, they would steal silent glances at each other.

Despite the many obstacles, these relationships blossomed. “I knew, I really knew, I was in love with him,” Dorothy said of Ermanno. In addition to the restrictions hampering their courtships, the young couples had to deal with an uncertain future, not knowing what would happen once the war was over.

In the fall of 1945, after the war had ended, word came that the Italian prisoners would be repatriated, in accordance with the Geneva Convention. This was wonderful news for the majority of the POWs but was bittersweet for those in relationships with American women. “We made a commitment that no matter what happened, we would get back together, even though at that time it looked like it would be a miracle,” Dorothy said.

The day of their departure in December, the girls and their families waited for trucks to come to transport the POWs to the train, where they would begin their journey back home. “I saw him get on the truck and he was looking down at me and we were waving,” Dorothy recalled. “The girls that had boyfriends going back were all crying. When I got back home, it was such an empty feeling. It was horrible, and the minute I opened the door there was a dozen American Beauty roses. The card read: ‘I love you and I will be back.’”

For two years, Dorothy made novenas (prayers) for what seemed to her like an impossible reunion. Ermanno could not come to the United States, and she could not go to Italy without chaperones—a long and expensive trip. “I was kind of getting into a depressed state because I thought nothing could come of it,” she said. “We could not even talk on the phone because connections were so awful, not like now.”

Then in 1947, her prayers were answered. Once they got the complicated paperwork sorted out, the parents of some of the girls engaged to the POWs agreed to accompany their daughters and other girls—including Dorothy and Mary Messina—to Italy. Dorothy and Mary married Ermanno and Antonio in a double wedding at the same cathedral in Cefalù, Sicily, where the sisters’ parents had married fifty years earlier.

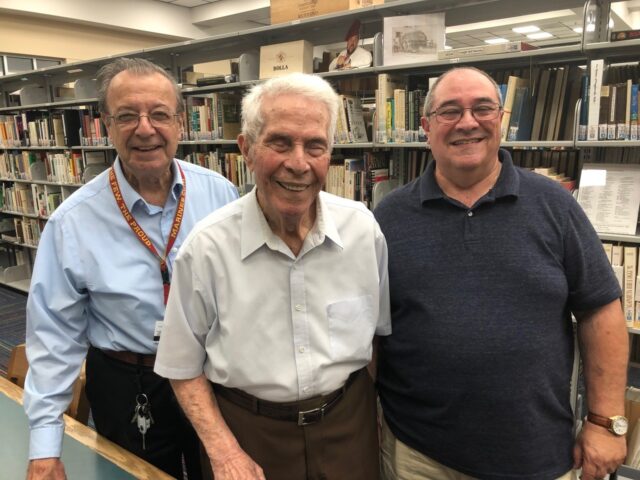

American Italian Archive Curator Sal Serio, Giovanni DiStefano, and his son Ron DiStefano in 2019. Photo by Elisa M. Speranza

Four of the seven Battaglia sisters—Vergie, Eleanor (“Noni”), Concetta (“Tini”), and Marianna (“Annie”), and their cousin Felicia D’Anna, married Italian POWs—Giovanni DiStefano, Lorenzo Nuzzolillo, Eugenio Chierici, Lorenzo Giacontieri, and Joseph Faroldi, respectively. POW Loreto DiGregorio met his future wife Mamie Lore. And Camp Plauche POW Giovanni Manfrin married Anna Mae Cassesi.

Marguerite Maranto said she never worried about what would happen next with her and Mario. “We were really in love. He was either coming back or I was going there, one way or the other.” She took her first airplane trip to join him in Italy in 1947. “It was my first time traveling out of New Orleans. I had just made twenty in May and got married a month later.”

Marguerite had a career working for the US Department of the Treasury in New Orleans, and Mario ran a Sheetrock contracting company. They were very active in the Jupiter and Venus Carnival krewes. Mario passed away in 1993. The floods that followed Hurricane Katrina destroyed the New Orleans East house they built, along with wedding photos, letters, and other mementos. But Marguerite said that she held all the wonderful memories of her life with Mario in her heart. Marguerite passed away in July of 2021.

Dorothy and Ermanno had a son, Gregory, and two daughters, Linda and Lisa. Mary and Antonio had a daughter, Marlene. Mary died in 1978 and Antonio in 1984. Ermanno passed away in 2002 and Dorothy in 2012. Their children and grandchildren still live in the Greater New Orleans area, along with many other members of the families that started with those dances behind barbed wire at Jackson Barracks.

Elisa M. Speranza lives in New Orleans. She’s the author of the forthcoming novel The Italian Prisoner, inspired by the story of the Jackson Barracks Italian POWs and their Sicilian American sweethearts. She can be reached at [email protected] or elisamariesperanza.com. These stories would likely have remained hidden from history without the vital support of Salvadore Serio (1934-2022), former Curator of the American Italian Research Library, housed at the East Bank Regional Library in Jefferson Parish.