Winter 1994

American Utopia

A history of the Llano del Rio Cooperative Colony in Vernon Parish, the longest lived socialist community in America

Published: October 1, 2017

Last Updated: December 19, 2018

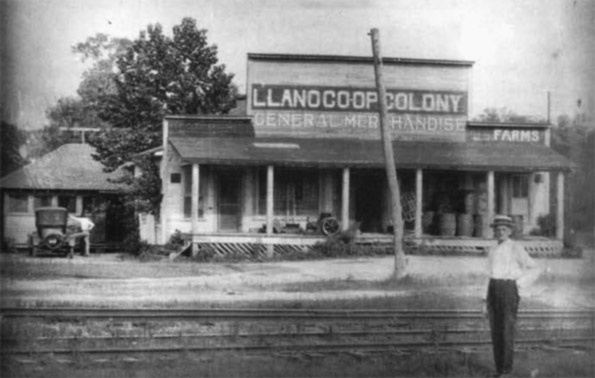

The New Llano colony served not only those who lived on the commune, but neighboring farmers as well. The opening of trade immediately established a rapport with New Llano's neighbors by bring new industries and skills to the rural hill country of west-central Louisiana.

Editor’s Note: In 1994, documentary filmmakers Beverly Lewis and Rick Blackwood produced American Utopia, an LEH-funded film about the Llano del Rio Cooperative Colony in Vernon Parish, arguably the longest lived socialist community in America (1914–c. 1939). The Museum of the New Llano Colony welcomes visitors on Thursdays and Fridays.

“A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing.” — Oscar Wilde

For a whole generation, the Llano Colony practiced what the rest of the American left preached: a livable wage, an eight-hour work day, an end to child labor, quality education and cultural opportunities, social security, affordable housing, and food and health care for all in return for an honest day’s work—ideas considered not just radical but subversive in their day. Perhaps the most surprising fact of all is that the Llano del Rio Cooperative Colony, founded in 1914, lasted so long not in its initial home of California, a state with a reputation for tolerance and liberality, but in conservative, rural Louisiana.

In California the colony’s voting strength marginalized and alienated its ranching neighbors, a cause of rising tension. The colony board realized that for Llano to survive it would have to move. In 1917 a specially chartered train transported over 200 colonists, their households, and their many industries to a defunct lumber mill town in west Louisiana called Stables, soon renamed New Llano. Many were excited by the new location; however, the move put a great economic strain on the colony, from which it never quite recovered.

Two Leaders/Two Styles of Leadership

Llano del Rio’s successes were due in part to two very different men who became the general managers of the colony and also the social commitment of the colony’s western and subsequent southern locations. Llano (pronounced ‘Yaw-no’) Colony was the brainchild of Job Harriman, a prominent socialist, lawyer, and seminarian, who served as Eugene Debs’ vice-presidential running mate on the Socialist ticket in 1900. For many years Harriman experienced first hand that few socialist victories were won at the ballot box. To Harriman’s way of thinking, the mainstream press and big business had a way of putting the worst possible spin on what socialism was all about.

It became evident to Harriman “that a people would never abandon their means of livelihood, good or bad, capitalistic or otherwise, until other methods were developed which would promise advantages at least as good as those by which they were living.” The idea evolved into the Llano colony, a self-supporting socialist experiment designed to provide “equal wages, equal education and social advantages, and equal comforts, including housing and commissary furnishings.” Harriman found ready backers. Capital was raised by selling stock to members who joined the colony, and land was purchased east of Palmdale in the Antelope Valley of Los Angeles County.

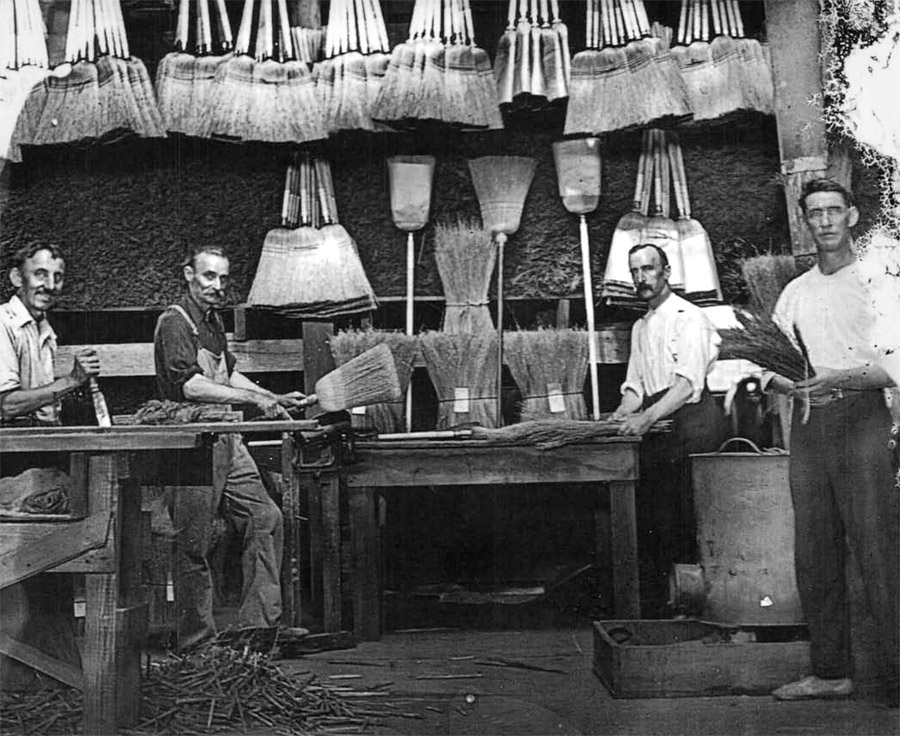

Everyone over the age of 18 at the colony had a job. Usually jobs were assigned, but people were allowed to change occupations if they were competent.

Celebrated author Jack London considered Harriman to be “the best Socialist speaker on the West Coast.” Another colleague described him as a man “of rare eloquence, deep sincerity, and irresistible personal charm.” Harriman’s powers of persuasion were such that within three years more than 1,000 residents flocked to Llano, far too many to sustain with the site’s limited water resources.

In theory, Llano del Rio Cooperative Colony was supposed to be a self-sufficient cooperative. New members were required to purchase 2,000 shares of colony stock, paying at least 25 percent up front (this fee was reduced in Louisiana). Membership money bought goods the colony needed to get the enterprise underway. Everyone over the age of 18 had a job. Usually jobs were assigned, but people were allowed to change occupations if they proved competent. In California, the colony advertised wages of $4 a day (the usual rate in California in 1914 was $2.50 a day), but the advertised rate could not be met until the colony was self-sufficient. In the interim, the wage became $2 a day—one dollar would be applied to food and housing, another to unpurchased stock, if there was money available. This was usually not the case.

In 1918, the Llano colony in California was abandoned, and approximately 60 families opted to move to Louisiana. The first years after relocation were the toughest. Harriman, suffering the final stages of tuberculosis, was soon forced to return to California. Many others departed in the first year, leaving a core group behind to salvage what was left. From within this group emerged George Pickett, the man who would be the colony’s only other General Manager until it went into receivership in the late 1930s.

The social services and programs at the colony proved to be decades ahead of their time.

Pickett’s and Harriman’s management styles couldn’t have been more different. Whereas the intellectual Harriman envisioned Llano to be a totally self-supporting cooperative in keeping with its status as a social experiment, Pickett, a former insurance salesman and real estate agent, saw an opportunity to bring into the colony desperately needed cash by making their goods available to their neighbors. Harriman had been the charismatic leader who sparked the flame; Pickett was the man who figured out how to stake it. In retrospect, history would tell us George Pickett was better suited to make these changes than Job Harriman. Pickett’s abilities were rewarded by fierce loyalty among these relocated colonists.

The Louisiana Economic Experiment

The opening of trade immediately established a rapport with New Llano’s neighbors by bringing new industries and skills to the rural hill country. Louisiana’s first artesian ice plant became one of the colony’s most successful ventures. People from as far away as Texas traveled to the colony to purchase blocks of ice. The colony opened the first library in Vernon Parish, considered one of the best in the state at the time. The blacksmith shop had an exclusive contract to do the metal work for the Kansas City Southern Railroad in that part of the country. Residents today can still recall how brand new shoes from the colony cobbler shop were as comfortable as if they’d been worn for two years. New Llano’s veneer plant turned out some of the finest woodwork in Louisiana. Then, too, New Llano was also the first town in Vernon Parish to have electricity.

The colony did not have hard and fast rules about how outside purchases were transacted. If someone from Leesville brought in grain to be milled, the colony would either take its percentage of the grain or accept cash. This cash provided the colony with funds for necessities like oil and fuel. Fortunate for parish residents, prices at New Llano were extremely reasonable because there were no employee wages or profit-gouging to jack up the products’ costs.

There was another factor in the parish’s acceptance of the cooperative colony, and that was the political sympathies that lingered in the hill country from the end of the 19th century. Forty years before Llano’s arrival in Vernon Parish, the lumber business had become one of the South’s most profitable industries.

A maypole dance in celebration of May Day at the Llano colony.

Like many other big businesses in its day, the industry was unregulated. The lumber owners controlled every aspect of their companies, including the workers: wages were paid in script (as company money was called), whole populations were carted around from one mill town to the next, and the workers were often in debt to the company-owned stores. As a result, some of labor’s first union organizing occurred in Louisiana, and west Louisiana became the site of one of the first labor strikes in America.

During this period, Louisianians supporting the unions considered themselves part of the Populist Party. By 1900 many West Louisianians were counting themselves socialists. In fact, during the 1900 presidential election, Louisianians registered more socialist votes per capita than almost any other state in the country—the very ticket that featured Eugene Debs and Job Harriman. “Big Bill” Haywood of The Industrial Workers of America (also known as the ‘Wobblies’) and Emma Goldman, a prominent activist and committed communist, made frequent stops at rallies in western Louisiana. In spite of the “divide and conquer” practices of the lumber companies by moving their workers around, the long and bloody labor strikes continued for decades, attesting to the fervor and commitment the disenfranchised workers felt for the social reforms the unions championed.

Perhaps the most surprising fact of all is that the Llano del Rio Colony lasted so long not in its home of California, a state with a reputation for tolerance and liberality, but in conservative, rural Louisiana.

By 1916, a year before the Llano colony moved to Vernon Parish, the I.W.W. finally gave up. This was due in part to the fact that much of the old growth timber in the region had been harvested. Profits fell and the companies began to sell off what they could.

In 1917, when the Gulf-Anderson Lumber Company arranged a sale of one of their abandoned mill towns and 20,000 acres to the Llano socialists, there was some apprehension on the part of the California colonists about their reception in their new Southern home. Though the word “socialist” was not foreign to the colony’s Louisiana neighbors, it had taken on new connotations since the May and November revolutions in Russia. However, Llano’s neighbors soon recognized that the lifestyle the cooperators brought with them incorporated many of the social reforms they themselves had fervently supported against the lumber companies.

Innovative Social Services

The social services and programs at the colony proved to be decades ahead of their time. The services were free and staffed by the members themselves. Seventy-five years before the Family Leave Act was passed, colony mothers had the option of taking up to six months off from work after the birth of a child. When they returned to work, childcare was provided. Years before the movement took hold in the South, a feminist revolution touched down in west Louisiana. Women, as well as men, were free to work in any area they were capable. For some women, this was in the sawmill; others chose more traditional jobs like cooking at the cafeteria or working in the sewing room.

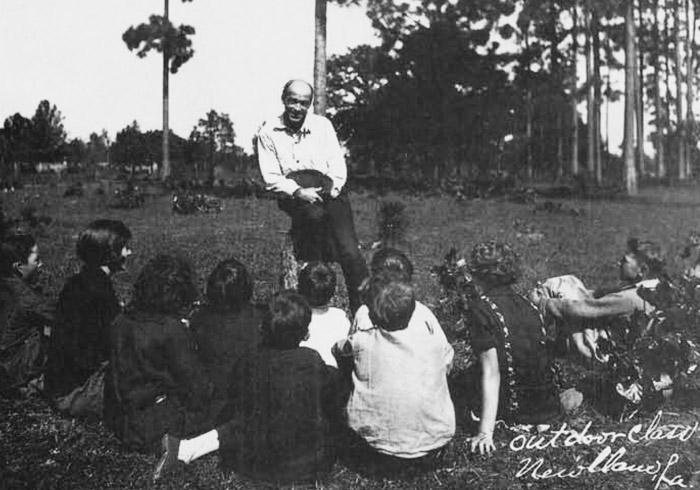

Education was of primary importace to the colony. Vocational instruction was stressed, and students were encouraged to offer alternative positions, even if they differed with the teacher’s. Here students meet at an outdoor classroom.

Education was of primary importance to the colony. After four hours of study, the older children worked four hours in some related industry, applying knowledge they had learned in the classroom. So successful was this distributive approach to education that it was common for colony children who had occasion to attend public schools to skip two grades. Schoolchildren might learn about construction, design irrigation systems, or operate and print a newspaper. Alternative opinions were encouraged in classroom discussions, even if they differed with the teacher’s. All that was asked was that the student know how to substantiate his or her position. Adults, too, availed themselves of night classes on topics as varied as philosophy, psychology, and the latest scientific farming techniques, sometimes augmented by visiting lecturers.

Medical care was available to any colonist who needed it, but it was often a mixed bag. New Llano was served by a chiropractor, Doc Williams, the only medical professional in residence. However, he was highly regarded by the colonists and later in Leesville where he and his wife Cecil practiced following the colony’s demise. Older people, no longer able to work, were cared for by the community. The colony’s health environment seemed, on the whole, a good one. During 1918, when people throughout the parish were felled by the flu epidemic, not one colonist died. Colonists also attributed their relative good health to various factors, including goat’s milk and a near-vegetarian diet.

Victim of the Times

Llano del Rio faded into oblivion upon its demise but it was famous in its own time. Over 10,000 people called the colony home at one time or another. In 1933, Senator Morris Shepard from Texas introduced Senate Bill 1142 to establish a federal corporation to organize self-sustaining agricultural and industrial cooperative communities financed by bond issues in an effort to alleviate the unemployment problem during the Great Depression. The only cooperative representative to address the Senate Subcommittee was George Pickett.

Despite its utopian aim, Llano del Rio was not a perfect world. Leadership positions remained predominantly male. There were restrictions on membership. Some colony families had outside income they used to purchase luxury items like butter and store-bought dresses, causing resentment from colonists without such resources.

Women, as well as men, were free to work in any area they were capable. For some women, this was in the sawmill; other chose more traditional jobs like cooking or working in the sewing room. Free day care was also provided. Here, several women take a break from shingling the roof of a building they will work in.

Human nature and history ultimately took its toll on New Llano. The colony’s history was sandwiched in between two of the country’s worst economic downturns. Both depressions impelled many to consider Llano as a viable alternative to an unstable life on the outside. The difference in the Louisiana experiment was that Llano in California had the momentum of being a new enterprise. In the late 1920s, the colony in Louisiana enjoyed some of its most prosperous years. It established several satellite colonies, including a produce farm in Premont, Texas, a cattle ranch in Gila, New Mexico, and a highly profitable rice ranch in Elton, Louisiana. Not surprisingly then, when the the stock market crashed in 1929 and banks began to fail, New Llano was overextended, and, like so many businesses around the country, faced financial ruin.

The colonists tried a variety of ways to get out from under debt and this factionalized the members. By 1937, Llano’s records and enmities were so complicated the community was financially paralyzed. It filed for bankruptcy and was placed into receivership. The receivership itself proved a messy state of affairs. The first receiver was declared “incompis mentis” and removed. The colony assets were so grossly undervalued and undersold at the receiver’s sale in 1939 that lawsuits ensued for the next 40 years.

A colony band plays at a funeral in New Llano. Frequent dances held at the colony were heavily attended by neighboring communities.

As history goes, the Llano del Rio Cooperative Colony has been written off as a failure, like so many other utopian communities. But was the colony a failure? As Dr. Robert Hine, a history scholar pointed out, “How do you call Llano a failure? When two-thirds of American businesses fail within their first three years, do you call capitalism a failure? Llano lasted 27 years, a good run for any corporation.”

By 1937, Llano’s records and enmities were so complicated, the community was financially paralyzed. It filed for bankruptcy and was placed into receivership.

During the next two generations, Americans enacted the Social Security Act, a minimum wage law, the Family Leave Act, and other social legislation, reforms we take for granted today. And while Democrats and Republicans take credit for enacting these reforms, what is lost to history is the fact that these ideas did not originate with these mainstream groups. Such causes were initially proposed and championed long before they became politically popular by those who took great risks of being blackballed, beaten, deported, jailed, and ostracized. Socialists, communists, labor unions, and cooperative communities like Llano del Rio all played their roles in bringing the need for reform into the American consciousness .

————————

Beverly Lewis and Rick Blackwood served as co-producers, directors and writers of American Utopia, funded in part by the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities and broadcast on Louisiana Public Broadcasting in November 1994.

People who joined the New Llano came from all walks of life, from most states in the union, and from many foreign countries. Because the cost to join in California was so high, members tended to be from the middle or upper middle-classes. A number of members paid on installment plans or traded their way into the colony allowing many from lesser incomes to be able to join.

A cross section of the colony’s male population reveals 70 percent hailed from farming and business sectors. The rest considered themselves professionals, factory and construction workers, clerks, and miners. No statistics list women’s professions before they entered the colony, but surviving records indicate several among them were architects and professors.

A fair number of these people considered themselves intellectuals and were philosophically attracted to Harriman’s socialist experiment. Principally, the colony advertised in socialist newspapers, so most of the members were of a socialist bent. However, membership in any party was not a requirement nor was a union card.

Race and ethnicity were certainly factors in the colony’s demographics, particularly when the colony moved to the South. The colony’s bylaws had no official word on any racial restrictions, but an official letter penned during the California period specifically indicated that “Mongoloids and Negroids” were not admitted. However, the colony did accept Jews, which was considered a very progressive step at the time.

Colonists making the move to Louisiana were philosophically torn about the race issue in the South. A number felt that no one who wanted to join should be turned away, especially African Americans, with whom the colonists intellectually sympathized. It is unclear if the migrating colonists themselves knew the extent of labor union activity in west Louisiana, but they expressed concern that coming in as a group of socialists might already be rocking the boat. Many feared that playing the race card in the segregated South might scuttle the whole venture.

Individual stories from the Louisiana colonists indicate that positive relations did exist with the nearby black communities. Colonist Septer Baldwin had just stepped off the train in New Llano with his family when he encountered a black family distraught over the impending breach birth of a family cow. Baldwin assisted in delivering a healthy calf, and from that time he was often referred to as “Doctor Baldwin” by the black community. Baldwin’s daughter, Rhea Cunningham, remembers walking into Leesville with black friends and having them say goodbye before they approached town and moved to the other side of the street. Llano’s General George Pickett would occasionally lecture in the nearby black community.

—Beverly Lewis