An Archive for Antoine’s

Organizing the history of the culinary icon

Published: February 28, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

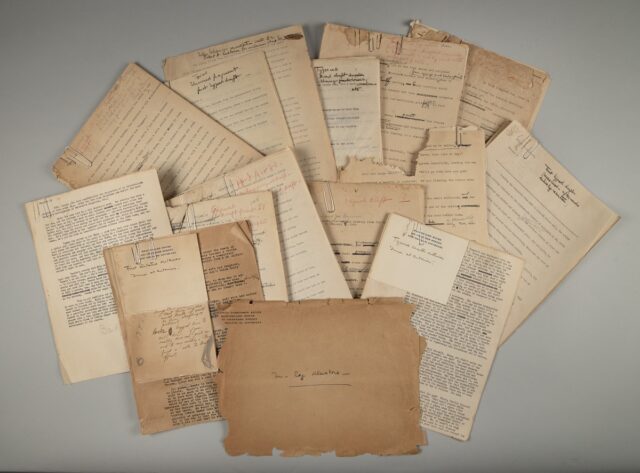

Photo by Sally Asher

Poppy Tooker surveys the contents of an Antoine’s storage room brimming with a century’s worth of ephemera.

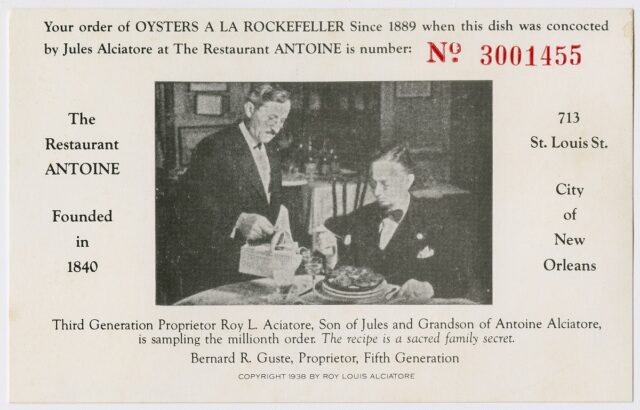

Antoine’s Restaurant is a landmark institution in the heart of the French Quarter whose 180–year history makes it the oldest continuously operating family-owned restaurant in America. There, on St. Louis Street, much of the canon of Creole cuisine was born—most famously, perhaps, Oysters Rockefeller, created in 1899 by Antoine’s son Jules Alciatore. It is a dish that Antoine’s great-great-grandson, Rick Blount, today’s proprietor and CEO, still serves with pride.

With food traditions like that, it’s big news when there’s a new chef in command of the city’s oldest restaurant—especially as retiring chef Michael Regua had guarded the secrets of Antoine’s kitchen for over forty years. Before the public announcement was made in January 2019, Blount asked me to join him for lunch, along with his wife, Lisa, to meet their new chef, Rich Lee, and have a taste of Antoine’s future. I was honored and thrilled to accept.

Sitting in the Annex, with the restaurant bustling around us, I remarked on the astounding history surrounding us. Lisa said, “You would not believe all the stuff that’s upstairs!”

Rick laughed. “My family has been hoarding here on St. Louis Street since my great-grandfather Jules closed the pension over a hundred years ago.”

Antoine Alciatore opened the original business as a boarding-house–style hotel and pension, with the dining room primarily meant for feeding the guests. The pension operated successfully for over fifty years. But by the late 1920s, visitors to New Orleans preferred the modern accommodations offered at the city’s many lavish new hotels, complete with twentieth–century conveniences such as private baths. Jules saw the restaurant as the business’s future. The third and fourth floors, where most of the pension’s rooms were located, were shuttered and locked, becoming fertile ground for Antoine’s early family archives, as Jules began to store books, papers, and other odds and ends in the empty rooms upstairs.

Jules’s second son, Roy Alciatore, began working at Antoine’s in 1917 at the age of fourteen. When Jules died in 1934, Roy found himself at the helm of the family restaurant with all the rich history and tradition that accompanied that responsibility. He saw clearly the value and significance of what his grandfather and father had accomplished before him and began a meticulous habit of saving every scrap of ephemera imaginable. Along with news clippings, ashtrays, celebrity photos, and autographs, Roy also began to amass menus and wine lists from across the globe, along with cookbooks and other food–related publications both in French and English. With over fifty thousand square feet encompassing seven adjoining buildings, his ability to collect seemed limitless.

Roy’s astounding treasure trove might have remained untouched if Hurricane Katrina hadn’t wrought such devastation on Antoine’s in 2005. An entire wall collapsed, leaving the upper floors of 713 St. Louis Street exposed to the elements, soaking much of the stored materials. Once wet, the weight of the storage further threatened the structure; temporary shoring walls were constructed while the rooms were cleared. Much was lost at this time, but anything salvageable was moved into a storage room that previously served as the restaurant’s laundry. With neither time nor money to further address the materials, they sat deteriorating in New Orleans’s unforgiving climate.

In 2012, Yale historian Paul Freedman learned of the restaurant’s archives while writing 10 Restaurants That Changed America. As one of the nation’s oldest culinary institutions, Antoine’s warranted its own chapter in Freedman’s book. When he first met with Rick Blount, Freedman was specifically in search of old menus. When shown the storage room, he was floored.

Accustomed to working in ancient European archives with documents dating back as far as the ninth century, Freedman recalled, “I had never seen anything like that room. Almost immediately I found a copy of Almanach des Gourmands, published in 1812, one of the first books about restaurants ever written. I advised Rick that there were many valuable artifacts there.” With the help of an intern, Freedman uncovered what he could in a week’s time, but the collection proved daunting, and when he returned to New Haven, the storage room doors were once again locked.

Shortly after their 2012 marriage, Rick showed his Seattle–born wife, Lisa Klein, the family storage. Lisa was fascinated, and with fresh eyes she began to sort through boxes in preparation for the restaurant’s 175th anniversary in 2015. “I came across additional pieces of the Roosevelt china, made originally for the president’s visit in 1937, which we used for the anniversary celebrations,” she remembered. But the room and its secrets were soon locked and abandoned once more.

My food–history interest was whetted by Lisa’s tale of the storage room, and finally, on a blazing hot day in June 2019, Lisa gave me my first glimpse of the archives. To get there, we traveled through Antoine’s huge kitchen and out onto the patio. We climbed a metal fire escape to the roof of the first–floor wine cellar, where metal frames that had once served as clotheslines for the laundry still remained. A short distance away, the padlocked doors awaited.

Beyond the padlocked doors was a pair of glass–paned French doors that swung open into a dark, musty space. The midday heat and humidity were overwhelming. I stepped into the room, and as my eyes adjusted to the light, I looked down to discover, just inside the doors, the skeletal remains of a river rat the size of a house cat—a startling first find indeed.

The storage area consisted of an adjoined pair of small, low–ceilinged rooms lined with built–in shelves. Everything was covered in deep dust. Here and there, containers held brown standing water collected from leaks in the roof. Piles of menus and wine lists dating back to Antoine’s 1940 centennial spilled from boxes, some marked with barely legible scribbled notations, haphazardly stacked on the shelves.

My hand lit on a stack of papers topped with the front–piece of a manila envelope with Roy Alciatore’s name scrawled across it. I picked up the stack and discovered it to be typewritten drafts of Frances Parkinson Keyes’s 1948 novel Dinner at Antoine’s. Notations in the margins in both Frances’s and Roy’s handwriting indicated the manuscript had passed frequently between them as she worked on the book.

There seemed to be no rhyme or reason to what Roy had kept. Nearby on the same shelf, there was a wad of yellowing paper, the size of a softball. Dated 1941, it was an entire year’s receipts from a Lakeview drugstore revealing Roy’s proclivity to stop on the way home from the restaurant for a carton of Carlton cigarettes and a fifth of R&R whiskey.

From that first visit, one thing was painfully clear—there was no way Lisa and I could pick through this huge, wildly mixed bag of artifacts in the heat and humidity of the storage room. Although the collection had somehow survived the elements thus far, the ongoing threat of damage caused by climate and conditions loomed large. Our first task was to find temporary storage space where the lot could be triaged.

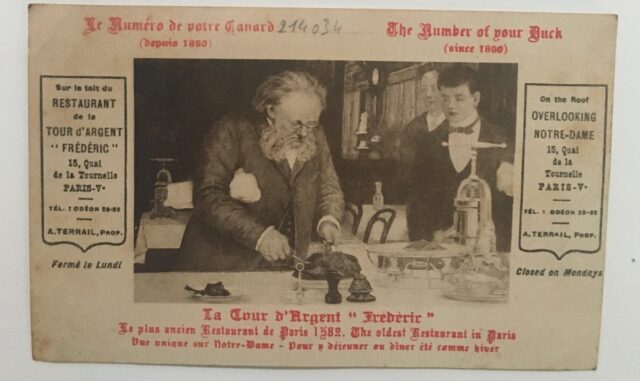

A souvenir ticket from Paris’s Tour d’Argent (above) inspired Roy Alciatore to create his own version for Antoine’s famous Oysters Rockefeller. The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Antoine’s Restaurant

Meanwhile, I could hardly rest between visits to the stifling hot room. On my second visit, a busboy moved a heavy rainwater catch basin to reveal some of Roy’s cookbook collection, including an Irish publication from 1796. Another visit revealed a stack of eight–by–ten photos of the restaurant’s interiors commissioned by Jules for his first souvenir brochure. They bore the signature of Pretty Baby photographer Ernest Bellocq, best remembered for his portraits of Storyville prostitutes.

Our first big break in the search for triage space came when I shared my plight with Brent Rosen, president of the Southern Food and Beverage Museum. His face lit up, and he said, “Let me make a phone call! I think I know where there could be temporary storage for you.” Within a day, the Solomon family agreed to let us move the materials into the nineteenth–century Carmelite monastery they had recently purchased on North Rampart Street with the intention of developing it as high-end apartments. Speaking for the family, Sam Solomon said, “We’re happy to help in any way with this important, historic project,” authorizing us to use the space for several months if needed.

A week or so later, as I wrapped up a Louisiana Eats! interview with Daniel Hammer, president of The Historic New Orleans Collection (THNOC), I shared my archive dilemma. “Daniel,” I began, “you know how they say to those much is given, much is expected?”

“Yes?” he answered curiously.

“Well, I’m afraid sometimes I’m that person.” I explained how daunting the task ahead seemed when it came to sorting through this amazing find.

Hammer explained that THNOC did not have the “dirty storage space” needed for sorting before remediation could be considered. But once he heard about the Solomons’ offer of the monastery as a sorting space, he asked, “What do you suppose the family wants to eventually do with the material?”

I repeated what Rick Blount had told me: “Poppy, I don’t have the funds or ability to save these things, but if they could be of value as research to anyone, I’d be happy to donate.”

Soon after, Hammer and THNOC’s curators presented the opportunity to the Collection’s board. Addressing the significance of the find, Hammer explained, “The continuity of materials is remarkable and very rare in the world of archives. Antoine’s history encompasses more than half that of the city itself. I see Roy Alciatore’s commitment to preserving the family papers as a heroic act.” The board agreed with Hammer, making the financial commitment required to preserve Antoine’s remarkable archive for perpetuity.

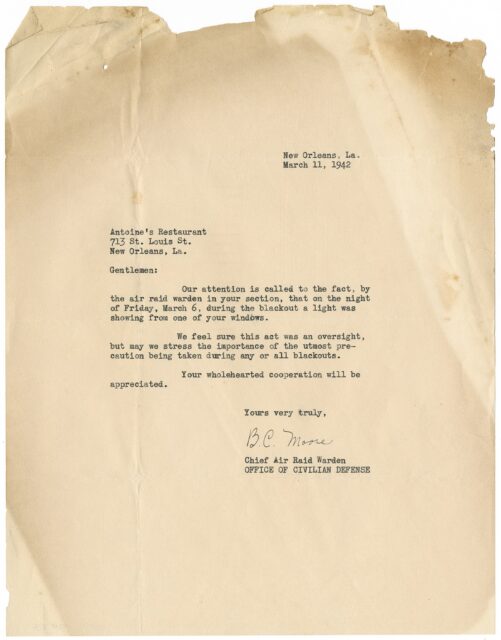

1942 letter from the Office of Civilian Defense notifying Antoine’s of a blackout violation. The Historic New Orleans Collection, gift of Antoine’s Restaurant

On an October day so unseasonably hot that it set records, THNOC associate curator Aimee Everett supervised as a moving team transported Antoine’s archives from St. Louis Street to the Solomons’ property on North Rampart. Prior to the move, Everett had been tasked with estimating the physical scope of the acquisition, something she recalled as a “massive, physical challenge.” Nearly 130 linear feet of materials were moved into the North Rampart Street property, with boxes and tubs of papers and photos lining a long sunny room inside the walled monastery.

Over the next two weeks, a crew of curators and cataloguers from THNOC volunteered their time to do the initial culling, setting aside old newspapers, periodicals, and books already part of the Collection’s holdings while exclaiming over countless incredible discoveries. “I’m from South Dakota, and I’ll never forget finding a 1940s telegram addressed to Roy from a pheasant farmer there!” Everett remembered.

From the early 1930s until his death in 1972, Roy Alciatore kept all correspondence in chronological files.Each original letter was pinned or stapled to a carbon copy of Roy’s reply, often with the postdated envelope attached as well. The subject matter of these missives varied wildly from a 1939 inquiry about a customer’s misplaced black sock inexplicably lost in the restaurant’s dining room to advice on rebuilding Antoine’s legendary cellar following Prohibition from wine expert and importer Alexis Lichine.

Mixed in with business correspondence were decades of deeply personal love letters between Roy and his future wife, Mary Pearl Duggan, whom everyone affectionately called “Bootsie.” Beginning with exchanges from Bootsie’s boarding school days at St. Mary of the Pines in Chatawa, Mississippi, the letters spanned their forty–plus–year relationship, often written on hotel stationery from places like New York’s Waldorf Astoria and the Savoy Hotel in London.

Once THNOC’s sorting was complete, Lisa Blount and I spent weeks poring over the boxes upon boxes of papers, photos, and books. We were rewarded with some marvelous discoveries. An Antoine’s business card from the late 1880s listed both Jules and his brother Alexandre as proprietors, a detail previously unknown to the family. When we came across an original souvenir ticket from Pariss Tour d’Argent restaurant, noting the ticket bearer’s order number for their famous pressed duck, we realized we had likely discovered the inspiration behind Roy’s Oysters Rockefeller souvenir tickets, an Antoine’s tradition that persisted into the 1990s. Roy’s version featured a photo of the restaurateur digging into the millionth order of his grandfather’s dish. A few items we discreetly removed for the family, including Roy’s personal diaries and what appeared to be Antoine’s official recipe book, with entries in longhand by both Jules and Roy, complete with Jules’s original Oysters Rockefeller preparation.

In early December 2019, the collection was packed onto pallets and transported by the Polygon Group to a processing center in Pennsylvania, where the material underwent two rounds in a blast freezer before it was cleaned and rehoused, then returned to New Orleans. Items that could not be treated by freezing (wood, glass, metal, and photographs) were held in isolation at THNOC until they could be treated in an anoxic chamber.

Rebecca Smith, head of Cataloging and Reader Services at the Williams Research Center on Chartres Street, estimates that the entire Antoine’s family archives will be accessible to the public within the year. Thanks to THNOC and the Blount family, the generous gift of Antoine’s archives are a legacy sure to delight and educate culinary scholars and Crescent City history buffs alike into the next century and beyond.

Author, radio host, and media personality Poppy Tooker is a native New Orleanian who has spent her life immersed in the vivid flavors of her hometown. Her most recent book, Drag Queen Brunch, debuted in the fall of 2019.