Spring 2023

Bad Romance, Bad Research

Cornell Woolrich’s Waltz into Darkness

Published: February 28, 2023

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

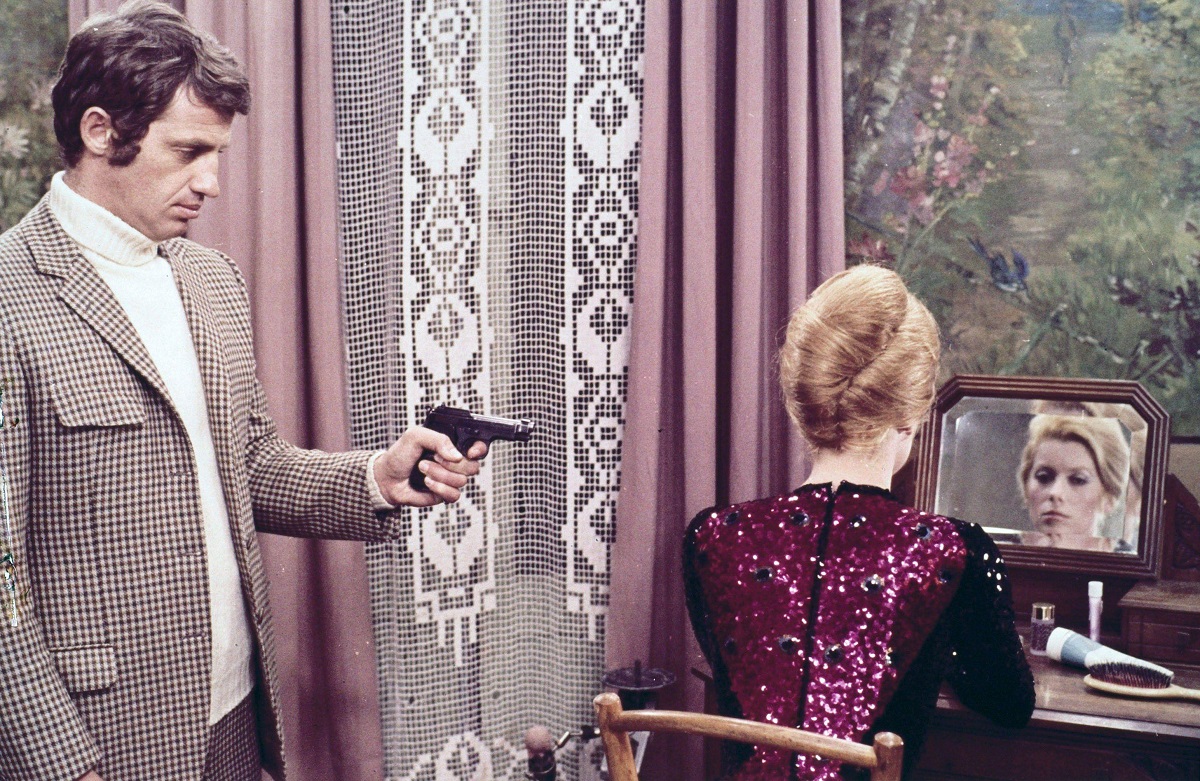

Alamy Stock Photo

Jean-Paul Belmondo menaces Catherine Deneuve in François Truffaut’s 1969 Mississippi Mermaid.

Louis Durand is thirty-seven years old, wealthy, and very much alone. “A man without a wife, he ain’t a whole man at all,” his maid tells him. “He’s just a shadow walking around without no one to cast him.” So Louis reluctantly but hopefully sends off for a mail-order bride, a raven-haired spinster from St. Louis. But the Julia Russell who eventually greets him at the riverboat docks is a young, golden-curled beauty, not the Julia Russell with whom he’d traded letters and photos. “So many men become smitten with just a pretty face,” Julia-not-Julia tells her husband-to-be. “I wanted our feeling to go deeper than that.” Louis has a confession of his own. He’s not a clerk in a coffee warehouse, as he described himself; he owns the business.

Despite their double deception, they honeymoon at Antoine’s, then an elegant dining establishment entering its fourth decade, today the city’s oldest, and arguably most old-fashioned, restaurant. There, they waltz “around and around and around; alone together,” Woolrich writes. “A waltz for life,” Julie whispers into her husband’s ear. “A waltz with wings. A waltz never ending.”

Interestingly, this wouldn’t be Antoine’s last turn around the literary dance floor. In 1948, the year after Woolrich’s novel first waltzed onto bookshelves, Frances Parkinson Keyes released Dinner at Antoine’s, a murder mystery that is everything Waltz into Darkness ain’t. Raised in New England, Keyes first visited New Orleans in 1940 before settling there permanently five years later (she also lived part-time in Crowley). Her South Louisiana–set fiction and nonfiction—Dinner at Antoine’s is the fourth of a dozen or so titles—involved immersive archival research and feature meticulously drawn studies of famous and obscure historical characters. In contrast, though he did pen an earlier New Orleans–set story, “Dark Melody of Madness” (1935), Woolrich never visited the city, as far as I can tell, and conjures up scenes as if drawing from vintage French Quarter postcards.

While Keyes’s book, Dinner at Antoine’s, was a bestseller, moving millions of copies, Waltz into Darkness, according to his biographer, “is no one’s favorite Woolrich novel.” Waltz into Darkness at times feels akin to the short-lived post-Katrina cop drama K-Ville, which managed to shoehorn a sappy Dr. John tune, a homemade fried shrimp po-boy (a sandwich no one makes at home), a white voodoo priestess, a racist Ninth Ward real estate developer, and something called a “gumbo party” all into its pilot episode. Woolrich inserts similar clichéd Crescent City simulacra: Foggy, ill-lit streets! Sleazy brothels! Mardi Gras!

But I prefer Woolrich over Keyes, who wrote in the same turgid style of contemporary local schlocksters like Lyle Saxon, Harnett T. Kane, and Robert Tallant, authors adept at turning New Orleans history into romanticized drivel. Though Keyes no doubt did her research, Dinner at Antoine’s suffers from bland exposition and whitewashed mythologizing on most every page. It’s a book that feels like it was written a century before. Meanwhile, for all of Woolrich’s patronizing stumbling around the New Orleans dance floor—he writes the city with two left feet—I found myself nodding along as Waltz into Darkness danced me around the city and into Louis and Julia-not-Julia’s ill-fated coupling. It’s a semi-believable bad romance that not only out-thrills Keyes’s novel but feels more in step with contemporary readers’ tastes. (Woolrich, more than Keyes, also made me want to revisit Antoine’s, to poke at whatever ghosts still waltz around those labyrinthine dining rooms.)

Julia-not-Julia, as you might have guessed, is not who she appears not to be. She refuses to open the trunk of clothes lugged downriver, drinks coffee instead of the cherished morning cup of tea she reported in her letters to Louis, smokes—gasp!—cigars, and eventually empties her husband’s bank account. She is—double gasp!!—an archetypical midcentury femme fatale.

Cornell Woolrich was nicknamed the “Poe of the twentieth century” and the “father of the modern suspense story.” At least three dozen of his stories have been adapted to film, most notably Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. Waltz into Darkness’s steamy scenario proved no less irresistible to filmmakers. French director François Truffaut transformed the novel into a feature with Catherine Deneuve and Jean-Paul Belmondo, titled Mississippi Mermaid (1969), which was decades later remade into Original Sin (2001) with Angelina Jolie and Antonio Banderas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, neither film is set in New Orleans.

I anxiously dashed through chapters as Louis tails his now on-the-run wife across the Gulf Coast, tick-tocking from Biloxi to Mobile to Pensacola like the hands of the Doomsday Clock (established in 1947, the same year as Woolrich’s novel).

Louis finally catches up with his beloved. “I only want you,” he tells her, “bad as you are, heartless as you are, exactly as you are, I only want you.” His betrothed was right: this is a waltz never ending. Divulging more would ruin the serpentine tale.

“You cannot walk away from love,” Woolrich writes early in the novel. And though his knowledge of New Orleans hardly extended beyond the menu at Antoine’s, Woolrich managed to capture something very true about the city: you must take her in your arms and dance.

Rien Fertel is the author of four books, most recently Brown Pelican.