“Better Than Doughnuts”

Fresh loaves at Jeanerette’s beloved staple, LeJeune’s Bakery

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

Photo by Christie Matherne Hall

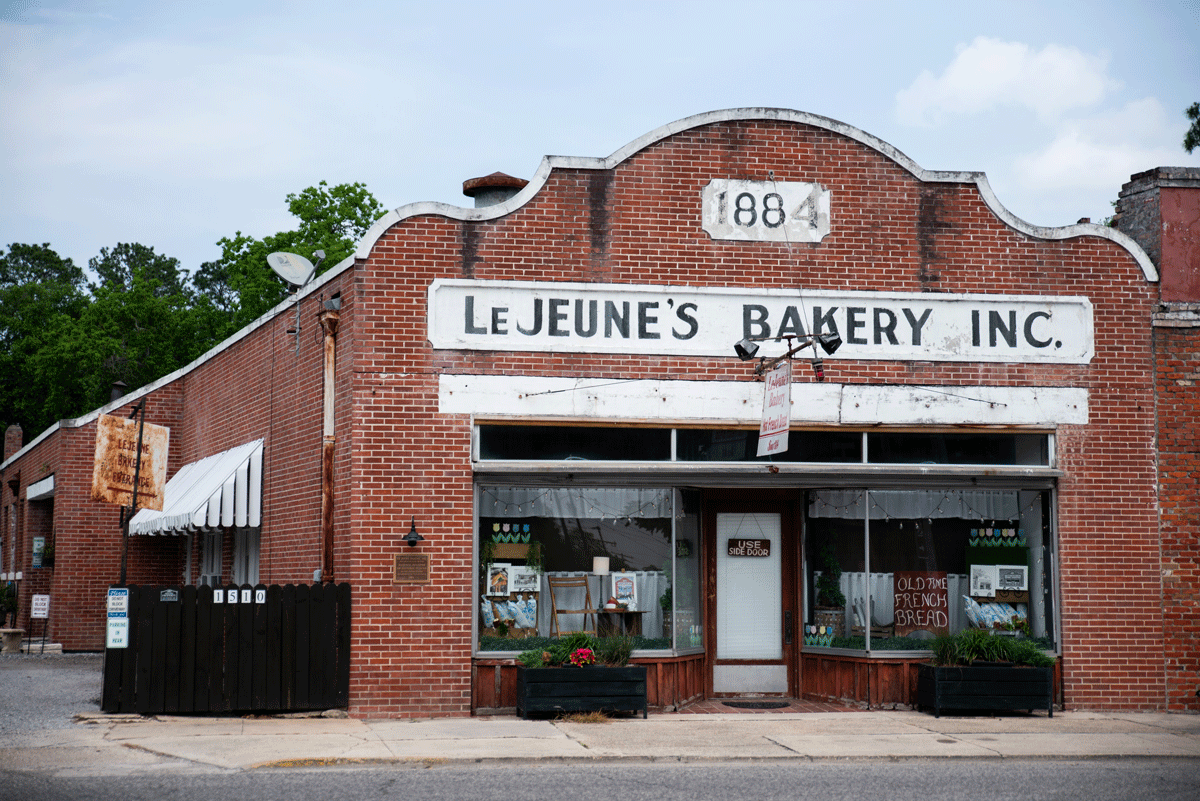

LeJeune’s Bakery in Jeanerette.

Just two blocks southwest of the Bayou Teche’s meander through Jeanerette, past a red brick exterior facade and through the side doors of LeJeune’s Bakery, you’ll find a perfect loaf of French bread. The outside is flaky and crisp, and the warm, pillowy middle invites a smear of salted butter. This ovalescent loaf, made by well-trained hands without modern industrial baking equipment or preservatives, has been the cornerstone offering of LeJeune’s Bakery for over a century, along with its signature molasses-infused ginger cakes.

The LeJeune family business opened in 1884, making it one of the oldest continuously operating bakeries in the United States. In 1884, Jeanerette was unincorporated, Main Street wasn’t paved, and the Civil War was a fresh memory. The first owner of LeJeune’s, Oscar J. LeJeune, built the bakery into a full-service staple stop in Jeanerette, selling everything from doughnuts to wedding cakes. The bread was first delivered by horse-drawn buggy, and later by the first automobile in Jeanerette. Current owner Ricky LeJeune is two years into his tenure; a native of Jeanerette, Ricky represents the sixth continuous generation of LeJeunes to helm the bakery.

Though Ricky hints at a secret ingredient or two, he claims the French bread recipe itself is simple: high-quality flour, no preservatives, made by hand. But a long-passed-down story in the family, told to Ricky by his father, suggests the recipe was not created by a LeJeune. Rather, it was won.

Our product is unique, but we can’t mass-produce it. There’s no other bread like that…

The Legend of “Zim” LeJeune

In 1918 two cousins—Walter LeJeune Sr. and O. A. “Zim” LeJeune—took over ownership of the bakery from the founder. Oscar LeJeune had originally named the business Old Reliable City Bakery; under the cousins’ tenure, the bakery was renamed LeJeune’s and remodeled as well. Walter was a sugarcane farmer, while Zim was educated as an attorney. But Zim never practiced law. Instead, he became a professional gambler.

Zim was well-liked in Jeanerette, according to Ricky LeJeune. He was a wealthy man during his time as co-owner of the bakery; he had a knack for card games and often won big. He once won a hundred-acre cattle farm and turned it into a neighborhood. Zim would give locals rent-to-own deals for the homes if they were unable to get a bank loan. “They had a parade for his funeral,” Ricky said.

One night Zim happened to be gambling against the owner of the other bakery in town. The other bakery owner was out of money and on the edge of losing the game, so he asked to see Zim’s cards.

“My Uncle Zim said, ‘Throw in your baker if you want to see my cards,’” Ricky explained. “So he threw in his baker, and he lost. That baker from the other bakery is where the French bread recipe came from.”

The family story doesn’t touch on how the baker felt about this exchange, nor does it reveal the baker’s name or which bakery he came from. The bread he baked, however, proved to be a boon to LeJeune’s, and bolstered the bakery’s longevity through the massive shifts in commerce through the mid-1900s, as interstates were built and superstores proliferated. The bakery was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2003, and its nomination document reiterated the precarity of small, family-owned businesses in the mid-twentieth century: “First came shopping centers out on the strip, then malls, then big box retailers that sold everything under one huge roof, from tires to what passed as French bread. The 1950s were twilight years for downtowns as centers of commerce lined with mom-and-pop businesses. LeJeune’s is indeed a remarkable survivor—a throwback to a previous era—embodying downtown commerce as it looked almost a century ago.”

A packaged ginger cake from LeJeune’s Bakery.

Surviving in Sugar City

Cane farming and processing have long been centerpieces of Jeanerette’s economy, earning it the nickname “Sugar City.” Ricky LeJeune is himself a sugar cane farmer; the cousin who passed the bakery to him was too. The cane sugar he grows finds its way back to his ginger cakes: “We buy sugar from one of the processors that we sell our sugar to,” Ricky noted.

During tough economic times—particularly throughout the 1960s and ’70s, when big supermarket chains began putting bakeries in their stores—the family’s sugar cane fields kept the bakery business alive. During the rough patch, LeJeune’s scaled down its offerings and kept only its most unique products: French bread and ginger cakes.

“This little town had three bakeries in the ’70s,” Ricky explained. “Other bakeries couldn’t survive it because [the bakery] was their sole money; that was it. The only reason [LeJeune’s] is still here is because Uncle Walter took money from the farm when times got rough . . . to keep the bakery going.”

Handmade Limitations

Ricky juggles the sunrise-to-sunset schedule of a farmer with running the bakery. He’s not the head baker, but he’s skilled at baking French bread, and clocks in at the bakery at 4 a.m. daily to help. The bakery produces anywhere between 300 and 500 loaves of French bread per day, and they also sell hot dog buns, pistolettes, and garlic bread. They ship bread and ginger cakes nationwide to online customers every Tuesday, and Ricky noted that they serve a handful of international tourists every week, visiting from Japan, France, and other countries. Regardless of the demand, the bakery has no plans to expand. Their business relies on skilled labor, a commitment to the traditional baking method, and use of historic equipment. “Our product is unique, but we can’t mass-produce it. There’s no other bread like that,” Ricky said. “I would say 80 percent is because of the way it’s done by hand. That old oven is another thing. It’s a Ferris wheel oven, and I think that adds to the bread and the recipe.” The bakery’s newest oven was purchased in 1942; they only stopped using a 1901 brick oven in 1987. Every other piece of equipment in the bakery is from the late 1800s to mid-1900s. The head baker has been working at LeJeune’s for over twenty years. The red light bulb in front of the bakery still lights up when the bread is fresh.

Ricky added that his favorite way to eat his French bread is to make French toast with it for his grandchildren. “They like it better than doughnuts,” he said.

Christie Matherne Hall writes about foodways, culture, travel, and natural disasters for 64 Parishes and Country Roads. She is also a podcast producer for the Western Colorado Writers’ Forum and an editor for wallethub.com, and enjoys helping people write their memoirs through the Story Terrace platform.