Sound Advice

Bold New Directions for Veteran Musicians

New releases from Charles Lloyd & the Marvels + Lucinda Williams and Walter “Wolfman” Washington

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 1, 2019

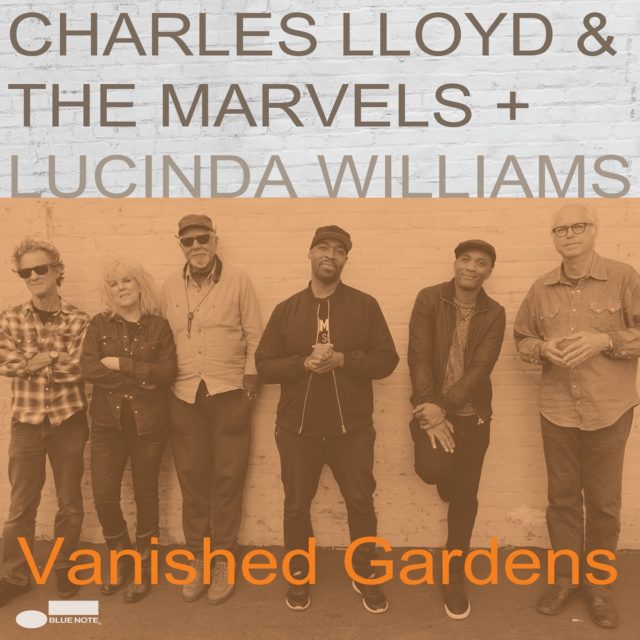

Photo by Dorothy Darr

Reuben Rogers, Greg Leisz, Eric Harland, and Bill Frisell (The Marvels) with Lucinda Williams and Charles Lloyd.

But some intrepid, forward-thinking musicians belie their advancing years with freewheeling experimentation, taking artistic chances at a time in life when most of their still-active peers have grown creativity calcified. The new album Vanished Gardens (Blue Note), by Charles Lloyd & the Marvels + Lucinda Williams, offers a powerful and fully realized example of this adventurous approach. It is all the more impressive because Lloyd and Williams are seemingly disparate collaborators. Lloyd, age 80 at this writing, is a saxophonist, flautist, and composer who has mastered a wide variety of jazz styles, distilling them into a distinctive personal sound. Williams, 65, is primarily identified with both country music and the amorphous genre known as Americana. Her impassioned singing and evocative songwriting—including many succinct Southern vignettes—meld twangy country with blues, R&B, gospel, swamp pop, and strident grunge-edged rock. Jazz does not figure into this mélange, apart from one brief line in her song “Righteously”: “Flirt with me, don’t keep hurtin’ me, don’t cause me pain, be my lover don’t play no game, just play me John Coltrane.”

While separating music into categories is inherently oversimplified and therefore imprecise, Lloyd and Williams have both accomplished much in the respective fields with which they are identified. Lloyd is best known for the 1967 album Forest Flower: Charles Lloyd at Monterey (Atlantic), a live recording that sold over a million copies thanks to great crossover appeal within the then burgeoning hippie movement. Lloyd’s acclaimed, prolific, and diverse work during the ensuing half-century—including numerous albums for the prestigious jazz label ECM—further account for his current stature as a venerated elder who remains in peak form. Williams has earned comparable iconic regard for four fecund decades of first-rate work, guided by fierce, uncompromising adherence to her artistic vision. Her 1998 album, Car Wheels On A Gravel Road (Lost Highway), set the bar for the prevailing aesthetic that still defines the Americana movement. She has won three Grammy Awards for her own work and written hit songs for other artists. Some of Williams’ best-known compositions are set in South Louisiana, reflecting her childhood years in Lake Charles, Lafayette, and New Orleans. Although no longer based here, Williams can still be cited as an important Louisiana musician.

Word that Lloyd and Williams were going to record together created some consternation among both artists’ followers. Jazz and country music are often regarded as mutually exclusive. But there is a rich history of interaction between these two genres that dates back some ninety years to the emergence of the still-popular hybrid known as western swing. To cite a more specific example, Jimmie Rodgers—the first major star in country music—prominently featured Louis Armstrong as an accompanist and soloist on his “Blue Yodel Number 9,” recorded in 1930. Such commonality is one reason why the Lloyd–Williams pairing constitutes an organic convergence. Another factor is Lloyd’s deep roots in the blues as a former sideman for such luminaries as B. B. King and Howlin’ Wolf. But the strongest raison d’être for this album’s existence is the palpable personal rapport between these two rugged individualists.

In 2018 Charles Lloyd and the Marvels released Vanished Gardens, featuring Lucinda Williams. Blue Note Records.

Vanished Gardens combines five instrumentals by Lloyd and his band, The Marvels, and five songs that feature Williams’ vocals. The album starts with the mellow, meandering, and thus curiously entitled “Defiant,” with lengthy ambient explorations by Lloyd, the celebrated guitarist Bill Frisell, the equally estimable Greg Leisz on pedal steel guitar, and an attentive rhythm section. As a signature instrument of country music, the pedal steel’s presence here firmly establishes this album as a multicultural statement within the prevailing context of Lloyd’s modern-jazz orientation. Williams’ first appearance is on “Dust,” with elegiac lyrics adapted from work by her late father, the noted poet Miller Williams: “There is a sadness so deep, the sun seems black, and you don’t have to try to keep the tears back . . . ’cause you couldn’t cry if you wanted to, even your thoughts are dust.” The blues/swamp-pop tempo of “Dust,” combined with Williams’ forlorn, deliberate phrasing, harken back to a huge hit from 1954, “The Things That I Used To Do,” by the South Louisiana–based R&B/blues star Guitar Slim. Williams is a great admirer of Guitar Slim’s timeless work.

Williams does not sing on the title track, “Vanished Gardens,” a rather abstract exploration of deliberate dissonance in the tradition of what is loosely designated as “free jazz.” She returns on “Ventura,” revealing her penchant, at times, for stark, glum, and deeply personal lyrics. But then Williams, Lloyd, and The Marvels dramatically elevate both the mood and their volume level on the melodic refrain: “I wanna watch the ocean bend the edges of the sun, then I wanna get swallowed up in an ocean of love.” This effective use of dynamics and sharply contrasting moods within one song are important expressive elements in Williams’ music.

Following an extended interpretation of her intense, fraught song “Unsuffer Me,” Williams infuses “We’ve Come Too Far To Turn Around” with a gospel feel. The anthemic theme of resistance evokes the current sociopolitical zeitgeist. Her final vocal is on an exquisitely understated rendition of “Angel,” by the late psychedelic blues-rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Accompanied only by Lloyd and Frisell, this ethereal performance ends Vanished Gardens on a harmonious note of spiritual redemption that resolves the angst of some of the previous songs. Lloyd and Williams have bravely stepped beyond their comfort zones with stirring results. It is neither premature nor excessive to describe Vanished Gardens as a contemporary classic.

The New Orleans R&B guitarist and singer Walter “Wolfman” Washington likewise explores new directions on My Future Is My Past (ANTI-). This soulful, subtle album was expertly produced by Ben Ellman of the funk band Galactic. Washington—highly respected on the New Orleans scene since the early 1960s—has accompanied such fine Crescent City singers as his cousin Ernie K-Doe, Lee Dorsey, and the brilliant yet sorely underrated Johnny Adams. Washington has also recorded prolifically on his own, most often with his tight, sophisticated band, The Roadmasters. This album, however, finds him atypically working solo or with minimal accompaniment. Washington uses this simplified soundscape to sing standards such as “What A Difference A Day Makes,” re-interpret K-Doe’s “I Cried My Last Tear” at half the speed of the original version, and give a pared-down arrangement to “Steal Away,” which he usually plays as flat-out funk with his full band. But the best song here—and one of the best New Orleans R&B recordings in many years—is Washington’s vocal duet with the esteemed Irma Thomas on the ballad “Even Now.” This elegant collaboration epitomizes the power of suspenseful silent intervals in music. In so doing it underscores the wise principle that less can often be more, which suffuses the entirety of My Future Is My Past. Like Charles Lloyd and Lucinda Williams, Walter “Wolfman” Washington chose to take an aesthetic chance. His inspired decision has paid off handsomely.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based writer, folklorist, producer, and the former drummer for the Grammy-nominated Cajun/Western swing band The Hackberry Ramblers. Sandmel’s published work includes Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, www.erniekdoebook.com, which was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities.