Summer 2018

Book Review: Freedom’s Dance by Karen Celestan and Eric Waters

New collection is dedicated to the social aid and pleasure clubs of New Orleans

Published: June 4, 2018

Last Updated: December 6, 2018

Along with the colorful and vibrant images of Mr. Waters and the narrative pieces of Ms. Celestan, the text provides a remarkable collection of essays and interviews by a most informed and engaging array of contributors. Included in this group are such astute scholars, artists, and veteran observers of the local cultural scene as James Borders, II, Rachel Carrico, Esailama Ortiz-Diouf, Freddi Williams Evans, Zada Johnson, Joyce Marie Jackson, Kalamu Ya Salaam, Charles Siler, Dr. Michael White, and Valentine Pierce. Of equal importance, of course, are the interviews with representatives of the Second Line culture themselves, the “every day people,” club members, and musicians, particularly such figures as Uncle Lionel Batiste (to whom the book is dedicated), Lois Andrews, Dr. White, Norman Dixon, Jr., and Fred Johnson. The striking pictures of Mr. Waters resonate with the stories.

The photographs of Mr. Waters bespeak a passionate understanding and love for his subjects. In light of this growing perception, he has become the “inside” photographer for those desiring representation of the city’s most colorful and dramatic culture bearers. Though primarily recognized for his documentary power, he is rapidly gaining accolades for his work in the domain of “art photography.” This is apparent in the critical reception of such exquisite, widely heralded works as those capturing the transformation of Dr. Michael White’s post-Katrina clarinets, the legendary shots of a leaping “Squirky Man,” and any number of iconic portraits of Uncle Lionel and others.

Freedom’s Dance screams, in the words of Kalamu Ya Salaam, “ an expression of our freedom to be ‘we’. Whoever we are, wherever we are, however we choose to be ‘we.’”

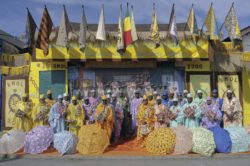

Most of the pages of Freedom’s Dance are dedicated to representatives of the Second Line culture in formal assemblage, expressing sartorial predilections that most outsiders would deem outre at best, with garishly color coordinated outfits and accouterments such as umbrellas and sashes. What the outsider does not get is that the “over the top” garb and group image are intended as a self-affirming act, a rejection of the oppressive dominant culture’s preference for the tepid. Like Amiri Baraka’s 1970 Black Arts Movement classic picture book, In Our Terribleness (done in collaboration with photographer, Billy Abernathey [Fundi}), Freedom’s Dance screams, in the words of Kalamu Ya Salaam, “ an expression of our freedom to be ‘we’. Whoever we are, wherever we are, however we choose to be ‘we.’” (“You Can’t Touch This,” Salaam). Borders (“New Orleans Negritude and the Second Line”) and Siler (“SAPC Accessories as Art, or Is It Vice Versa?”) vigorously reiterate this sentiment.

As noted earlier, narrative contributions run the gamut in Freedom’s Dance, from the hard-core documented historical research of Joyce Jackson (“New Orleans Second Line Aesthetics and Identity”) to a light cameo interview appearance by the ubiquitous Uncle Lionel (with Waters and Celestan). Jackson’s thoroughness is underscored with references to Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, John Blassingame, and others. The presence of solid historical and cultural study is apparent also in the contributions of Freddi Williams Evans and Zada Johnson (“Freedom Dances across the Diaspora”). The section on habanera rhythms is particularly compelling and would, perhaps, like other musical sections of the text be made more so with incorporation of an exemplary CD.

Because they play such a vital role in the Second Line culture, the musicians bring a unique perspective to this matter. Hence their additions as interviewees. Dr. Michael White, Wanda Rouzan, and Gregory “Blodie” Davis reflect in their commentary great sensitivity to the musician’s special calling and those experiences which contribute to their personal growth and professional development. The interviews also give a good bit of emphasis to the importance of repertoire and musical trends, especially for the musician who wants to remain relevant to the Second Line Culture.

Of all the interviews, those of veteran club members provide the deepest insights into the organization and function of today’s SAPCs. Their observations uniformly reflect a concern with the negative impact of inflation on the tradition. They were more divided on such issues as gender equity, however, with the women getting powerful advocacy from Lois Andrews and Barbara Lacen Keller, respectively representing the Baby Dolls and the Lady Jolly Bunch. Another major concern among the longtime members is the fear that the groups are deserting their avowed commitment to benevolence and being vilified by the violence brought to their activities in large part by non-club members.

New Orleans’s favorite son, the late poet Tom Dent, left us a poem a propos the Second Line culture. His “For Lawrence Sly” takes the form of admonition for an inveterate young second liner. It also recaps the history of the struggle, the cost of racism, and, yes, the necessity and joy of umbrellas, both real and metaphorical.

—

Henry C. Lacey is Professor Emeritus of English at Dillard University.