Brown Pelican

An excerpt from Rien Fertel’s latest book from LSU Press

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

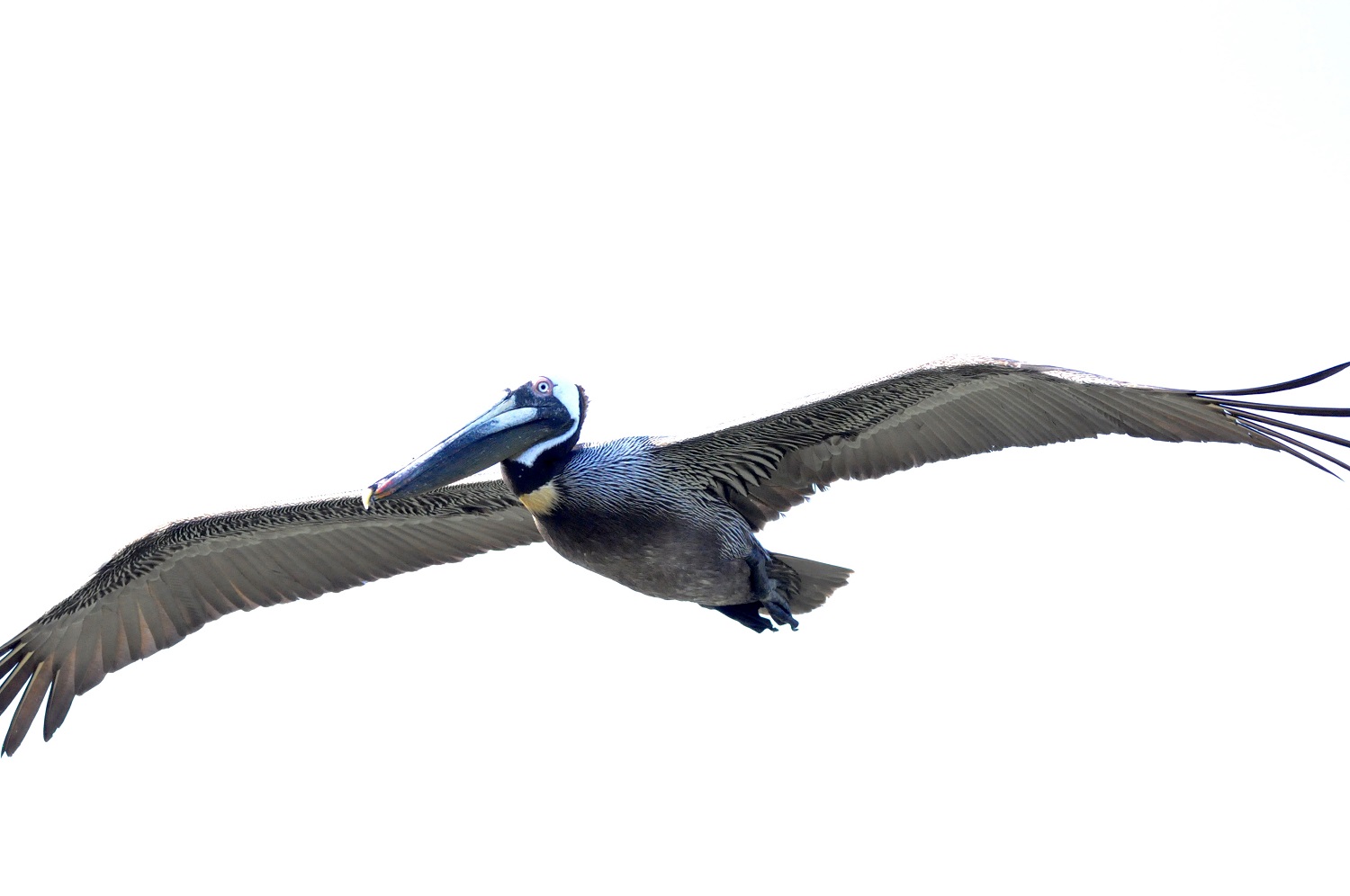

Photo by Rien Fertel

Pelican in flight.

I might have been the fish the brown pelican swallowed.

—Jane Hirshfield, “Day Beginning with Seeing the International Space Station and a Full Moon Over the Gulf of Mexico and All Its Invisible Fishes”

Walter Inglis Anderson loaded his supplies into his small, hardly seaworthy skiff: a small ream of cheap typewriter paper, a notebook, pens, pencils, watercolors, and enough sepia ink to last a week or three. He was a New Orleans–born bohemian, an eccentric father of four who required solitude, a schizophrenic who escaped his last stay in a mental hospital by knotting bedsheets and lowering himself down from an upper-story window. Following his escape, orderlies discovered that he had filled the walls of his room with soap-drawn sketches of birds, aflight and free.Anderson was an artist—a prodigious and, in his lifetime, sorely unappreciated one. Following six years of art school in New York and Philadelphia, he moved to Ocean Springs, Mississippi, where he assisted in his brother Peter’s pottery studio. There, he began to perfect the singular, meditative vision that would define his life’s work: tracing the mystic chords that connect humanity to the natural world, or what he called “the miracle of realizing that art and nature are literally one thing.”

Beginning in the mid-1940s, after turning forty and shortly following his last diagnosed psychotic break, Anderson started rowing thirty miles out to the Chandeleur Islands, off the coast of Louisiana, to find peace, to create art. He bivouacked on North Island, which he called North Key, high atop an oyster shell midden, warming himself by a driftwood fire, amid a nest of mangroves, in the midst of the world’s largest colony of brown pelicans.

LSU Press

“The whole island seems a concentration of life,” he scribbled in his notebook: shorebirds and migratory passerines, seabirds and sea life, mosquitoes and no-see-ums. He captured this island menagerie—his “familiars,” he called them—with ink-dipped crow quills, paper, and paint. Birds were his main inspiration: ducks, herons, and egrets, terns and gulls, red-winged blackbirds, storm-borne frigates, ospreys on the hunt and pipers at play, cormorants, mergansers, grackles, gallinules. According to his daughter Mary, “When he saw a bird, he was that bird.” But he cherished the brown pelican most of all. An inescapable presence along the Gulf Coast, pelicans were his obsession, his most familiar familiar, “his totem and a spiritual guide.”

Who knows why we pick a person, a plant, an animal to fall in love with. For Anderson, perhaps it was fate—he was born the same year, 1903, that President Theodore Roosevelt saved the brown pelican from local extinction by designating the nation’s first wildlife refuge at Pelican Island, Florida. The following year, Roosevelt carved the nation’s second wildlife refuge from the Chandeleurs and the adjoining Breton Islands. Shuffling such synchronicities aside, we know that Anderson took pleasure in being in the presence of pelicans and never tired of portraying them on the page. “He might draw a hundred pelicans,” one biographer wrote, “or one pelican a hundred times.” And on North Island there were many thousands of pelicans to draw.

Anderson sketched the pelicans in what he called “all their reactions and conditions of life”: soaring, feeding, returning, repeating, loafing, nuptialing, nesting. He reveled at their synchronized movements, their “tremendously musical harmonies of rising from the ground at my approach.” He learned to live not only with pelicans but as pelicans live: bathing as they bathed, walking the beaches barefoot just like they did (though he lacked their four webbed toes). He slept in a makeshift tent or under his boat, but sometimes gathered dried grass, he wrote, “to make myself a nest like the Pelicans.” He even claimed to have learned the pelican’s language, and compiled a lexicon, the “Pelican Dictionary of Common Terms,” despite the fact that the bird, once it has fledged and left the nest, hardly ever speaks:

Tchoo: falsetto, used endearingly.

Arp or arp bow wow: [no definition provided.]

Arrh-h-h: when the mother flies over, perhaps with food.

Why-ah: very shrill.

Kerr-uph: [no definition provided.]

Arr-uh-Arr-uh: when the mother bird arrives with food.

Quieh-hh-qui-eh-h: often accompanied by flapping of wings.

Aw-awh-aw-aw: [no definition provided.]

Pelicans were the artist’s agony and his ecstasy. He mourned the sick, buried the dead, and celebrated the pelican colony’s rebirth each spring. He subsisted on fish and oysters, but often ran out of food and resorted to salvaged tin-can jetsam, their labels worn away, or the rare pelican egg, rolled free from its nest. They “taste good but the consistency [is] nauseating,” he admitted, and are “better raw than cooked.” Anderson consumed pelicans and they consumed him, literally. One afternoon, while drawing, he was “attacked several times by a pugnacious young pelican who tried to swallow [his] bare foot.” A few days later he took part in an “ecstasy of feeding” of hungry nestlings. “Today I assisted at an orgy,” he wrote, “a religious . . . feast with the passion and excitement of sexual delirium. I drew while it went on, sitting beneath the mangrove bushes.”

“After you have lived on the island for a while,” Anderson wrote, “there comes a time when you realize that the pelican holds everything for you.” He resembled the weary but resolute wanderer featured in Psalm 102: “I am like a pelican of the wilderness: I am like an owl of the desert. / I watch, and am as a sparrow alone upon the house top.” Alone, he never grew lonely. But despite the countless hours he spent in their presence, for all the times he put pelican to page, the artist regretted that “it’s impossible to get all you want.” There were always more pelicans to paint, until the time came when there weren’t.

Walter Anderson, Pelicans on North Key, c. 1950. Watercolor on paper. Gift of the Friends of Walter Anderson, Walter Anderson Museum of Art.

Birds, besides Norman Bates, were for me both there and not there, omnipresent and invisible. Though I grew up surrounded by water and trees—prime bird real estate—I paid those flying, twittering creatures no mind. Until I became a passionate, day-to-day, list-building birder during the coronavirus pandemic, I could identify only a dozen or two birds common to my home state of Louisiana, including the brown pelican, of course. She was that plump-pouched beggar pleading for scraps near fishing docks, the beachfront drifter, my state bird, emblazoned so beautifully—not to mention beatifically—on our state flag, which, with an image of a Christlike mother pelican piercing its breast to nurture her chicks on her own lifeblood, should come with a trigger warning for anyone with a blood phobia, a complicated relationship with the Catholic Church, or a mother.

Pelican researcher Juita Martinez with pelican. Photo by Liz Bourgeois.

But what most defined the pelican for me was the summer blockbuster that arrived in theaters one month before I turned thirteen: Jurassic Park. Allow me to narrate the film’s final minutes, in case you’ve forgotten or, perish the thought, have never seen Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece. A tyrannosaurus rex does dino battle with a pair of raptors, allowing the failed theme park’s survivors to escape Isla Nublar by helicopter. As John Williams’s score soars toward the credits, the camera pans around the chopper’s cabin. John Hammond, played by Richard Attenborough, remorsefully regards his amber-encased mosquito, while his two grandkids nestle in the arms of Sam Neill’s Dr. Alan Grant, who finally accepts his destiny to be a father. Laura Dern’s Dr. Ellie Sattler sits across from him, expressing her love with tear-brimmed eyes. She glances outside; he follows her gaze. Five brown pelicans flap their wings, majestically gliding into a Pacific Ocean sunset. That brief but remarkable montage distills and dramatizes the film’s main message: that “life finds a way”—humans will make babies, humans will make mistakes to the great detriment of those babies, dinosaurs will evolve into birds, and the cycle of Jurassic Park sequels will never end.

Whoever picked the pelican from the casting call’s list of Hollywood hopefuls keenly chose the right bird. The earliest known pelican fossil, excavated from the Luberon mountains of Southern France, dates to the early Oligocene Epoch—some thirty million years ago. That proto-pelican is nearly identical to today’s bird, though endowed with a slightly longer beak. For that reason, the brown pelican and her seven sister species of the family Pelecanus—the great white pelican, Peruvian pelican, American white pelican, pink-backed pelican, spot-billed pelican, Australian pelican, and Dalmatian pelican—have been called “living fossils” and “one of the most superficially dinosaur-like of the world’s 10,000 or so bird species.” Walter Anderson agreed, grouping pelicans with the “earlier and more primitive forms of life” and dubbing them “prehistoric monsters.”

Anderson stopped visiting North Island at some point in the late 1950s, switching his allegiance to Mississippi’s Horn Island. Maybe the aging artist found the shorter, but no less arduous, trek to Horn more feasible. Perhaps a recent string of hurricanes had finally rendered North Island’s silty shores uninhabitable. But I like to think he stopped rowing out to the Chandeleurs once the pelican population plummeted.He speculated—correctly, it would turn out—that pesticides were to blame for the eclipse of the brown pelican along the Gulf Coast, but biologists would not validate that hypothesis until several years after his death. All Anderson could do was watch and paint as the pelican vanished—first gradually, then dramatically—and was finally snuffed out completely, like a beachfront campfire in a tempest. “In a word,” he would write about the bird, “you lose your heart to it. It becomes your child and the hope and future of the world depend on it.” The pelican had disappeared from North Island, and with it had gone the artist’s hope, his future, his world.

In mid-June 1965, Anderson readied his skiff for what would become his penultimate island adventure. On his second day, he walked to Horn Island’s far westerly point, where, a mile in the distance, he spotted a pair of pelicans sailing out to sea. He celebrated his good luck. “Providence,” he wrote, “has been kind.” Eleven days later, fortune smiled upon him once again: “Three pelicans—then six pelicans,” he rejoiced. “Time has gone back.” Independence Day greeted him with a miracle: the largest pod of pelicans he’d witnessed in well over a decade. “Pelicans!” he wrote, “seventeen in one flock!” On September 9, Hurricane Betsy roared ashore, decimating Horn Island, where Anderson rode out the storm with his skiff roped to his waist. As the sun greeted the next morning, he discovered his island of familiars gone. Less than three months later, on November 30, Walter Anderson would succumb to lung cancer in a New Orleans hospital.

Nestling pelicans on Philo Brice Island. Photo by Rien Fertel.

That same month, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Science Advisory Committee released the nation’s first comprehensive report on what we would, decades later, understand to be a global climate crisis. “Pollution now is one of the most pervasive problems of our society,” the report warned. “Vast quantities of wastes and spent products . . . pollute our air, poison our water, and even impair our ability to feed ourselves.” By decade’s end the West Coast’s largest brown pelican colony would, like the one on North Island, dissolve due to exactly what that report heralded. The living fossil risked fossilization, not for the first time and not for the last, as man and bird both stumbled toward extinction.

This book tells the story of our fraught and often savage relationship with a single species of bird, the brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis), but inevitably it also speaks to our relationship with the planet and our relationship with ourselves, our own humanity, or lack thereof. In the roughly 150 years of history this book traces, the pelican has been poisoned, beaten, mutilated, and murdered. It’s worth remembering, bears repeating like a secular mantra: this did not have to happen. No part of this had to happen.

For many millennia, the pelican has existed as a symbol of saintly piety. Today, the brown pelican is considered a bellwether bird, or, for biologists, an indicator species, able to portend what disasters await. In truth, those two metaphoric pelicans—one mythic, the other scientific—are one and the same. If “‘hope’ is the thing with feathers,” as Emily Dickinson famously wrote, without feathers, we can presume, hope dies.

The brown pelican provided Walter Anderson with hope and with a purpose—several purposes, perhaps: artistic, spiritual, communal. For a man who found it hard to love his fellow man, Anderson found in pelicans a creature to love. But love, as he well knew, as we all know, equals loss. The grief he must have felt as his most precious familiar became unfamiliar, is a grief—a grief for our planet, its creatures, ourselves—we will all share as we head into an uncertain future. That much is certain.

Rien Fertel’s Brown Pelican debuted in 2022 from LSU Press. Visit lsupress.org for more information or to buy your own copy.