Buddy Bolden’s Blues

Did a simple vitamin deficiency cause the jazz pioneer’s mental illness?

Published: June 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

The only known photo of Bolden, in which he appears with members of Kid Bolden’s Ragtime Band. Bolden is standing, third from left.

I thought I heard Buddy Bolden say, dirty nasty stinkin’ butt, take it away . . .”

—from Jelly Roll Morton’s 1939 recording of “Buddy Bolden’s Blues”

In the spring of 1906, the innovative, influential New Orleans cornet player Buddy Bolden became bedridden after experiencing headaches and mental impairments that included deep depression and delusions. Bolden is thought of today as the most creative and important figure in the early years of the music that later was dubbed jazz. But that year, things began to go terribly wrong for him. It was the beginning of the end.

Bolden was already a heavy drinker, writes biographer Don Marquis, but his alcohol use seemingly spiraled out of control as he careened toward a series of psychotic episodes. “Frustrated, he began to drink even more than usual, perhaps trying to wash from his mind the musical ideas that besieged him and with which he could not cope,” Marquis writes in his acclaimed book In Search of Buddy Bolden. “In fits of depression, he blamed his friends, as well as strangers and sometimes even his cornet, for his imagined shortcomings.”

On March 25 of that year, the situation escalated. Bolden jumped out of bed at his home on First Street in New Orleans and hit his mother over the head with a water pitcher, accusing her of trying to poison him. The police were summoned. Bolden was arrested. A contemporary newspaper account of the incident, which was lost to history until it was discovered by this writer two years ago, cites Bolden’s drinking as the cause of his mental impairments. “Alcoholic indulgence converts negro patient into a dangerous man,” says the headline in the Daily States. It was the first of three arrests of Bolden on insanity charges. After his third arrest, about a year later, Bolden was committed to the Louisiana Insane Asylum. He would spend the rest of his life there. His reign as the king of New Orleans music was over.

There are many mysteries about Bolden’s life, but chief among them is just what caused his mental illness, which was diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia (known at the time as dementia praecox). Part of the problem is that not many records exist. It didn’t help that medical treatment for poor black men who ran afoul of the law and who were deemed to be insane was almost nonexistent. With few facts to go on, conjecture has proliferated. That Bolden may have had syphilis is one theory that crops up from time to time, despite a complete absence of evidence. It gets worse. Marquis notes in his biography that “some of the superstitions explaining Bolden’s demise have a voodoo flavor about them.” One take by Louis Armstrong, who was just a child when Bolden was locked away, seems to fit in that category: “Buddy Bolden was a great musician,” Armstrong writes in his 1954 autobiography, “but I think he blew too hard. I will even go so far as to say that he did not blow correctly. In any case he finally went crazy. You can figure that out for yourself.”

The main building of the East Louisiana State Hospital, then the State Insane Asylum, in Jackson, to which Bolden was confined for much of his life. Photo by Charles L. Franck, The Historic New Orleans Collection

In 1907, the very year that Bolden was sent away, a mysterious, devastating epidemic was sweeping across the South for the first time since the Civil War: pellagra. Sometimes known at the time as “sharecropper’s disease,” pellagra has not received significant consideration as the possible cause of Bolden’s mental illness until now, perhaps in part because the disease is largely forgotten in the developed world. It was just emerging in the public’s consciousness as Bolden’s symptoms manifested; as doctors became more familiar with the disease, pellagra diagnoses skyrocketed. (It is thought by some researchers to be under diagnosed even today.) The disease’s progression, its risk factors, and its typical symptoms track closely with what little we know of Bolden’s downfall. “The dementia of pellagra is very similar to the dementia praecox of schizophrenia,” writes Abram Hoffer in the journal Psychosomatics in 1970. Pellagra was widespread in insane asylums across the South in this era. It was thought to be present in at least 10 percent of all asylum patients in the region, according to one study, and presumably at a far higher rate among patients with major risk factors, which at the time included being poor and black, being manual laborers, and having a long history of heavy alcohol use.

Buddy Bolden checked all of those boxes.

An estimated three million Americans had pellagra in the first half of the twentieth century, according to a citation in a report posted on the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and nearly one hundred thousand of them are believed to have died as a direct result of the disease. According to a document on pellagra prevention published by the World Health Organization, pellagra was a leading cause of death at insane asylums in the South.

Pellagra, we now know, results from a chronic deficiency of niacin, a form of vitamin B3. But in Bolden’s lifetime, it was not well understood. For a time, in the era when illnesses like yellow fever were being brought under control, it was feared that pellagra was a communicable disease—that people were going insane and being sent to asylums, where they would contract pellagra from other patients. Later it was thought to be linked to corn that had spoiled. It wasn’t definitively attributed to a vitamin B3 deficiency until shortly before World War II. The enrichment of foods starting in 1941 is among the factors that have virtually eliminated it from the United States today.

Pellagra takes its name from the Italian word for rough skin, a common symptom that is typically most visible on the hands and upper chest. But the skin condition that gives the disease its name is not always present among patients, especially those with alcohol-use disorders; one 1981 article from the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry notes that twenty alcoholics that researchers determined, after necropsies were conducted, to have had pellagra were never diagnosed in their lifetimes because “in the majority, there were no skin lesions.” Whether Bolden had a skin condition is unclear—there is only one known photograph of him; it shows him with a later iteration of his band. He is wearing a long-sleeved shirt and jacket, and his hands are partially obscured. It seems unlikely, though, that a black person, and particularly one who was poor, would have been thoroughly examined for dermatitis in this era. Any doctors who examined Bolden immediately after his arrests and before his institutionalization almost certainly had no training in identifying pellagra and no knowledge yet about how to properly treat it. And according to an article written by Thomas Sancton Sr. and published in the Second Line magazine in 1951, “regular medical examinations apparently were instituted in 1925” at the Louisiana Insane Asylum, nearly two decades after Bolden was institutionalized.The skin condition was also believed to be less visible in patients with dark complexions. According to a story published in Public Health Reports in 1996, Joseph Goldberger, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize for his work linking pellagra to diet, chose to test his theories on white inmates at a prison in Mississippi in 1915. The author quotes a contemporary newspaper article on Goldberger’s work, saying the white inmates were picked because pellagra was “easier of diagnosis, and more unmistakeable in its symptoms, among Caucasians.”

Descriptions of other symptoms commonly found in pellagra patients are hauntingly reminiscent of what we know about Bolden. For instance, in Pellagra: An American Problem, published in 1912, author George M. Niles describes “cephalalgia of the severest sort” (i.e., headaches) as being a common complaint, along with a steep mental decline, “deepening from discontent to sadness, sadness to melancholy, melancholy to conformed melancholia, and on down the psychic decline to dementia.”

“These poor creatures are easily frightened, easily panic-stricken,” Niles writes. “They seek escape in flight, and hallucinations of poison often make them refuse food and drink to the point of inanition. As in some of the other delusional insanities, they are prone to feel the greatest antipathy for and fear of their dearest relatives and friends, attributing sinister motives to all attempted acts of kindness.”

The timing of the major known events in Bolden’s mental breakdown also seems like a possible clue. For instance, people with pellagra often had periodic psychotic episodes, such as those that afflicted Bolden, rather than a suddenly continual and permanent psychosis, at least in the earlier stages of the disease. These episodes tended to occur from year to year in spring or early summer. The thinking is that diets of marginalized people were even less varied during the winter, when produce was scarcer, and the resulting niacin deficiency would result in symptoms by spring and summer.

Bolden is known to have been arrested three times in New Orleans before he was finally sent to the insane asylum. The first was in the spring, on March 27, 1906; the second was in the summer, on September 9, 1906; and the third in the waning days of winter in the year he was committed, on March 13, 1907. What is believed to have been Bolden’s last public performance as a musician in New Orleans also came in the summer, during the Labor Day parade in 1906 amid an overbearing heat spell; Marquis writes that Bolden was felled either by exhaustion or “from some conduct.” (An “extreme aversion to all forms of exercise” and “weakness, particularly marked in the legs” were described as common ailments of pellagra patients in the 1919 book Pellagra.)

Sheet music for “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” in the version popularized by Jelly Roll Morton. The New Orleans Jazz Museum

Another typical symptom may bring to mind a reinterpretation of the famous lyrics of Bolden’s signature song, which is thought to be at least partly autobiographical. There are several variations on the tune, which is known alternatively as “Buddy Bolden’s Blues,” “I Thought I Heard Buddy Bolden Say,” and “Funky Butt,” and which is thought to have originated toward the end of Bolden’s career—that is to say, not long before his physical and mental impairments are known to have begun.

Many of them make reference to Bolden himself describing a “funky butt” or “stinky butt” and calling for a window to be opened to “let the bad air out.” The first known specific reference to the lyrics is slightly different. Willie Cornish, who had played in Bolden’s band, told a reporter for Louisiana Weekly about the song in 1933. “The real words are unprintable,” wrote E. Belfield Spriggins. But what Cornish gave him as a sanitized version seems to describe cheap booze that was associated with digestive problems: “I thought I heard Old Bolden say, rotten gut, rotten gut, take it away.”

Diarrhea is another common symptom of pellagra, one of the three D’s considered hallmarks of the disease. (The others are dermatitis and dementia. Sometimes a fourth D—death —is added.) In fact, it is often the first symptom to surface. The conventional wisdom on the “funky butt,” “stinky butt,” and “let the bad air out” passage is that it refers to the smell generated by a crowd of people dancing enthusiastically to Bolden’s music, but is something else at play? Wouldn’t the windows of a music venue have already been open in the era before air conditioning in New Orleans, except on especially cold days? Is the “funky” smell coming from someone’s posterior simply body odor, or is it possible that the “bad air” references what the World Health Organization describes as “profuse, watery” diarrhea that afflicts many people in the first stage of pellagra?

Then there is the matter of major risk factors. The 1981 report from the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry describes the link between alcohol use and pellagra as a “conspicuous association,” and notes that “the disease has virtually disappeared in developed countries, except in association with chronic alcoholism.” Descriptions of Bolden’s chronic alcohol use are included in both public records and contemporary press accounts. And Bolden’s drinking was legendary among fellow musicians for years to come. “Buddy used to drink awful heavy,” wrote clarinetist Sidney Bechet in his 1960 autobiography, “and it got to him in the end.” “He was crazy for wine,” bassist Albert Glenny, who had played with Bolden and claimed to have been drinking buddies with him, was quoted as saying in the 1955 book Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya.

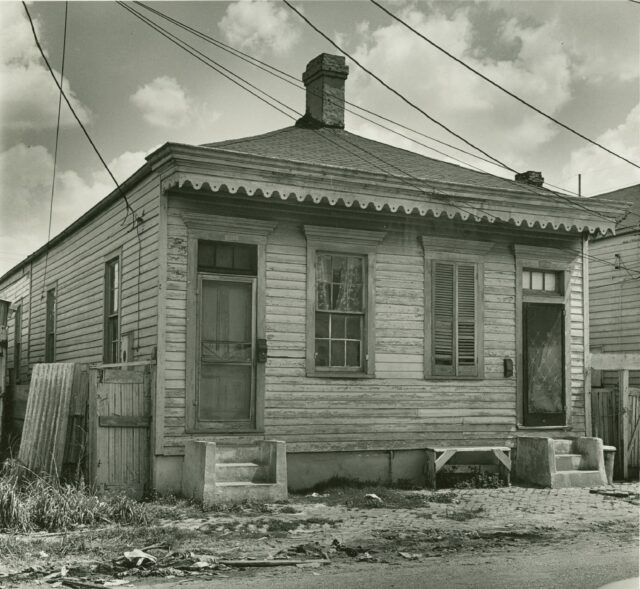

The disease was also thought to affect people at far higher rates if they were impoverished and black and worked manual labor jobs—the three being inexorably linked in the Deep South. Presumably a major contributor to this link was that people who were marginalized tended to have diets that were less varied than people who were wealthier and of higher social status, and those diets were more likely to be made up primarily of foods that contained insufficient amounts of niacin. Bolden, a black man who grew up in the early years of Jim Crow, was considered the most popular black musician around the turn of the century in New Orleans, but that did not translate into financial security. Sometime after his first arrest, Bolden’s family moved to a different house on First Street, one that Don Marquis described as “much shabbier” than the modest home at 2302 First Street. They had moved “partly for lack of rent money,” Marquis writes. When Bolden was arrested a second time, the address recorded by police was a vacant lot. In records of his last arrest, he was listed as a laborer. He was described as “filthy” in the document that condemned him to the asylum. “Cause of insanity: Alcohol,” the document says.

This house at 2309-2311 First Street in New Orleans, pictured in 1955, is where Bolden lived throughout most of his career as a musician. William Russell Photographic Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection

“A definitive diagnosis of pellagra is not possible,” said Dr. John J. Hutchings, an associate professor of clinical medicine at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans who has expertise in both gastroenterology and psychiatry and who has routinely treated patients for vitamin deficiencies. “However, given the historically described symptoms and known local prevalence of nutritional deficiencies, it certainly would be prudent to include pellagra in the differential diagnosis and consideration as a potential contributor to the untimely demise of Mr. Bolden.”

Don Marquis, the Bolden biographer and jazz curator emeritus of the New Orleans Jazz Museum, agreed pellagra could have ended the career of the first king of New Orleans music. “It sounds good to me,” he said in an interview in January. “It sounds very logical, very legitimate.” Ted Gioia, whose books include Music: A Subversive History and The History of Jazz, called the pellagra theory “very plausible” in an interview. “I’ve written about the connections between musical innovation and medical conditions,” Gioia said. “It’s a recurring theme, traced in my latest book back to ancient Egypt. It’s no coincidence that New Orleans was both the birthplace of jazz and least healthy major US city, circa 1900. So the idea that a physical disorder, rather than latent mental instability, is the cause here seems quite plausible.”

If Bolden’s mental illness and institutionalization and the end of his music career were caused by pellagra, the tragic story of his downfall is all the more heartbreaking. The disease is both preventable and treatable; patients are given extremely high doses of vitamin B3, not unlike how scurvy patients are given massive doses of vitamin C. But Bolden, even if he had been diagnosed with pellagra during his lifetime, never would have been treated, because the riddle of the devastating disease was not solved until 1937. That year, a University of Wisconsin professor named Conrad Elvehjem discovered that dogs suffering from pellagra recovered in a matter of days if they were given nicotinic acid or nicotinamide—niacin.The vitamin was soon tested on human pellagra patients, and the typical results were stunning: “almost complete relief of the irritation of the mucous membrane of the mouth and digestive tract and the disappearance of acute mental symptoms within 48–72 hours,” according to the World Health Organization.

But it was too late for Buddy Bolden. His family had stopped visiting him around 1920, when he could no longer recognize them, according to Marquis, and he never recovered his sanity. He died at the asylum hospital in the early morning of November 4, 1931. The cause of death was cerebral arteriosclerosis. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Holt Cemetery in New Orleans—the precise location of which remains yet another mystery.

James Karst is a jazz history researcher and writer best known for discovering that Louis Armstrong had been arrested at the age of 9 on a “dangerous and suspicious” charge in downtown New Orleans.