Magazine

Buona Sera

“Buona Sera” is New Orleans through and through, a song suffused with both poetry and party.

Published: September 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

And there are mountains. What New Orleans song has mountains?

Throughout his storied career Prima wrote and performed more overtly New Orleans tunes. For years he traditionally closed his nightclub act with “When the Saints Go Marching In.” He even adapted a Creole tune and gave it the odd phonetic title “Ai-Ai-Ai-May-Pay-May-Lay-Ma-Sa.”

In fact, “Buona Sera” is not even the most popular Prima song. It never was a big hit like “Just a Gigolo,” “Sing, Sing, Sing,” or even “I Wanna Be Like You,” from Prima’s turn as King Louie in Walt Disney’s The Jungle Book.

Yet “Buona Sera” is New Orleans through and through, a song suffused with both poetry and party.

Its origins lie in a World War II military mistake. The Army had sent glider pilot and songwriter Carl Sigman (whose hundreds of compositions include “Pennsylvania 6-5000,” “A Marshmallow World,” and “Where Do I Begin,” the theme song to Love Story) to Sicily by error. “He was stranded there for a couple months until he was picked up again, and fell in love with the Italian language,” his son, Michael Sigman, recalls in a recent phone conversation. The accidental diversion would result in a number of Italian-flavored lyrics, including “Buona Sera,” which coupled Carl Sigman’s friend Peter DeRose’s melody to the sweep of Sigman’s cinematic scene:

In the morning, signorina, we’ll go walking

When the mountains help the sun come into sight

And by the little jewelry shop we’ll stop and linger

While I buy a wedding ring for your finger

In the meantime let me tell you that I love you

Buona sera, signorina, kiss me good night

Terry Sigman is Carl Sigman’s widow. Now ninety-two, she met her husband in the late 1940s while working as a personal assistant to Prima, when the songwriter visited Prima’s offices in the Brill Building in New York City’s Tin Pan Alley. “When I hear Louis sing ‘Buona Sera,’ I get very emotional,” she says, during an interview conducted with her son’s help. “It takes me back to those days at the Brill, where I loved working for Louis and where I met the love of my life.”

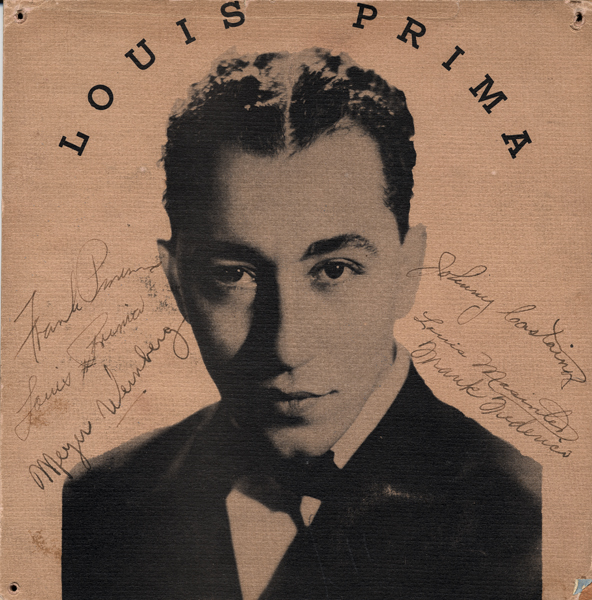

By the time Prima met Carl Sigman, Prima’s reputation was already well-established. Born Louis Leo Prima in 1910 to Italian immigrants, he grew up exploring the French Quarter and Tremé neighborhoods, where music didn’t erase racial and social barriers but it frequently crossed them. Prima was influenced by everything from minstrel shows to opera, but especially jazz: when he heard Louis Armstrong, he discovered a major influence on his own sparkling trumpet style and gravelly scat vocals. Whether fronting small combos or big bands, Prima would become as well-known for his stage antics and vernacular wordplay as for his musicianship. His humor was especially important when performing Italian-themed novelty songs during a peak of wartime anti-Italian sentiments. “He could turn a word and get a laugh any time he wanted,” said bandleader Woody Herman.

In 1947, Prima (along with other artists) enjoyed hits with satirical Sigman numbers such as “Civilization” and “The Thousand Islands Song.” He didn’t fare so well three years later when he released his first attempt at “Buona Sera” on Mercury as a B-side. “Prima tries to gravel-throat his way thru an Italian-flavored love ballad. It doesn’t come off,” said Billboard in its review.

Billboard was right. While an overwrought choir intones the lyrics behind him, Prima pleads in a maudlin spoken interlude: “Don’t go, signorina. Kiss me, signorina.” Sigman’s evocative verse drowns in orchestration. A similar version by Dean Martin a few years later was no improvement.

The story of “Buona Sera” might have ended there, but something about the song must have appealed to Prima, because he brought it with him to Las Vegas. In a now-fabled eight-year residency at Sahara’s Casbar Lounge with his then wife, vocalist and comic foil Keely Smith—and backed by a charging band called The Witnesses—Prima began including “Buona Sera” in his late-night and early-morning sets. In 1956, Capitol Records cut Prima, Smith, tenor sax player Sam Butera, and the rest of The Witnesses live in the studio for what would become Prima’s finest and most celebrated album, The Wildest! Butera’s jump-blues arrangements fire up a new version of “Buona Sera” that was almost unrecognizable to its songwriter.

“He was absolutely shocked by it,” Michael Sigman says of his father, Carl. “I remember him saying more than once, ‘I wrote this nice sweet simple love song, and here this guy turns it into something completely different.’ He was just stunned.”

The choir was mercifully scrapped. The tune is now launched by a dramatic habanera rhythm, an echo of the New Orleans “Tango Belt” of Prima’s childhood. From there the tempo shifts to a shuffle, until Butera’s sax blasts a warning and sends the song careening toward rock and roll. Prima and company take their listeners from a nostalgic past to a neon future, promising both love and unflagging energy.

For reasons Michael Sigman can’t quite figure out, the re-imagined “Buona Sera” developed a rabid following in Germany as well as in a number of eastern European countries, spawning numerous cover versions. It was prominently featured in the 1996 movie Big Night. Yet “Buona Sera” hadn’t yet fully made its mark as a New Orleans song until the evening of April 11, 2010, when the HBO television show Treme used it as the centerpiece of its premiere episode.

It is one of the most affecting musical montages ever seen on television. A deejay rants about New Orleans music clichés—the “sad Big Easy–Crescent City–care forgot” songs—until he falls at last into the studio chair, takes a deep breath, and flips a switch.

With that, “Buona Sera” begins, and scenes of the show’s various characters roll by. As Prima sings of the Mediterranean, a tugboat chugs up the Mississippi River. Prima blows his trumpet, and a trombonist toots on his mouthpiece for his child’s delight. A weary couple shares a bottle of wine and a rare laugh on their front porch; a Mardi Gras Indian chief surveys his home’s damage; a frazzled chef is soothed by a proffered dish of gelato; a bar fight breaks out. It is New Orleans as a city of grace and heartbreak, simple gestures of affection and the constant threat of violence.

Unlike many songs used in Treme, “Buona Sera” was written into the original script. “The song works historically for New Orleans and for local essence, but ‘Buona Sera’ also has a great sense of civic place in the romance of a loved city,” says Treme creator David Simon in an email. “In the case of the song it’s Naples, which is a port city and has the feel of a romanticized place. New Orleans speaks in the same vernacular for America, but here the imagery is of a broken and half-emptied city. So the romance and affection you hear in the song lands as irony, and it’s bittersweet.”

There’s yet another way to appreciate “Buona Sera”: as a paean to stamina. The stamina it took Louis Prima to reinvent himself again and again. The stamina it took to play Sahara’s Lounge at all hours. The stamina of a Sam Butera sax solo. The stamina that can be required to live in New Orleans. It might be just the song for a city that in its three hundredth year is encroached upon by warming oceans, facing a future that can be generously called uncertain.

“In the meantime let me tell you that I love you,” sings Louis Prima, a promise for our city’s meantime, for all our meantimes.

Michael Tisserand is the author of Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White. He can be contacted at www.MichaelTisserand.com.