Summer 2017

Cajun Strong

Advances in genetics provide new hope for Acadiana’s close-knit population of Usher's syndrome carriers

Published: June 8, 2017

Last Updated: March 25, 2022

The Starbucks staff are ready for tonight’s Deaf/Deaf-Blind chat. They have gift-wrapped their door prize and cut slips of receipt paper on which deaf customers can write their orders. Group organizers Dan and Annie Arabie, who are both deaf-blind, arrived early. The ambient light tonight is low, a familiar challenge to those with low vision. Dan checks that enough tables are available and accessible. He makes his way to the counter to place his order, his hand following the table edges and his white cane rhythmically tapping the tile as he sets his path. At the counter, he takes a heavy black marker from his pocket, feels the edges of the order slip, and writes his request for lemon cake and the coffee special. His experiences of taste, smell, and touch are big, much bigger than for those who see and hear. He finishes his cake quickly so his hands will be available for talking. More friends arrive, usually in twos. The deaf-blind are often accompanied by a Support Service Provider (SSP) who is employed by the state to drive them and assist with activities like shopping or doctor’s appointments. Those with Usher syndrome experience deteriorating peripheral vision from retinitis pigmentosa (RP), leading to progressive tunnel vision that robs them of driving privileges and the independence that comes with it. However, the independence of deaf-blind Cajuns in a hearing, sighted world is supported by training offered at Affiliated Blind of Louisiana in Lafayette, one of the few training centers nationally that has a significant deaf-blind staff and clientele.

Dan Arabie at home in Lafayette.Photo by Theresa Zaunbrecher

About twenty-five have gathered for the chat tonight. Several generations of deaf-blind Cajuns are regulars. Philip Quibodeaux, in his sixties, returned to Louisiana from Seattle after his retirement a few years ago. His SSP, Monica, drove him here from Amelia Manor Nursing Home, where he is one of about a dozen deaf-blind residents. Dan and Annie are empty nesters still in the workforce; Dan is a case manager at Amelia Manor, and Annie is employed by a national department store chain. Among the young adults with Usher syndrome is Kaleb Bowen, a student at South Louisiana Community College, who has cochlear implants and uses hearing, speech, lip-reading, and American Sign Language (ASL) to communicate. Not all the deaf-blind in attendance are Cajuns; Felicia came from New Mexico for training at Affiliated Blind and stayed, and Nathan and Erica, a couple from Tennessee, relocated to be part of a larger deaf-blind community. Quite a few are here tonight from Lafayette High School, the site of the main Deaf program in Lafayette Parish and one of the first schools to offer ASL as a second language. Everyone is conversing in different forms of ASL. Those with severe vision loss, like Philip and Dan, use tactile ASL exclusively. One signs while the other listens by placing his hands on the signer’s, a skill they develop in parallel with their vision loss. When Dan and Philip chat, they rapid-fire alternate between speaker and listener by trading hand positions. They use facial expressions liberally, just as they did before they lost their vision and just as hearing people do while talking on the phone. Annie uses a tracking form of ASL by holding the forearm of the ASL speaker centered in her visual field, especially when ambient light is low. The younger generation are conversing in standard ASL. ASL speakers in Acadiana use a smaller space for their signs compared with elsewhere, a character of the dialect that has been attributed to the prevalence of Usher syndrome in the state. At least half the group here tonight supplement ASL with oral speech, which is common among those who use hearing aids or cochlear implants, and is welcomed by ASL novices.

Tactile ASL is used by deaf people who also have vision loss. Photo by Theresa Zaunbrecher

Like others in his generation, Dan’s diagnosis of deafness did not come until he was a toddler. His family had limited communication with him until he started school at Louisiana School for the Deaf. It was heart wrenching for the Arabies to put their confused, crying six year-old son on a bus to the state school, but they knew this option was better than the lifelong isolation experienced by earlier generations whose communication was limited to gestures invented by the families themselves. By the time he had his first weekend back home six weeks later, he was much happier and more confident, because he finally was learning to communicate and make Deaf friends. His younger deaf-blind brother Arnold joined him later, and their parents and all four brothers ultimately learned ASL. Dan graduated in 1980 as valedictorian of his class, but he did not follow many of his classmates to college right away. He wanted to get married, have a family, and start working. It was not until after his vision loss forced him to give up his career at the US Postal Service and his girls had grown that he finally pursued his bachelor’s degree at Gallaudet University in Washington DC. This was an accomplishment for a mature student in a new city, made even more challenging by his advanced vision loss. Having his new wife, Annie, cheering for him from home made their long bus rides to and from Louisiana worth it, and he earned his bachelor’s degree in Psychology in 2014.

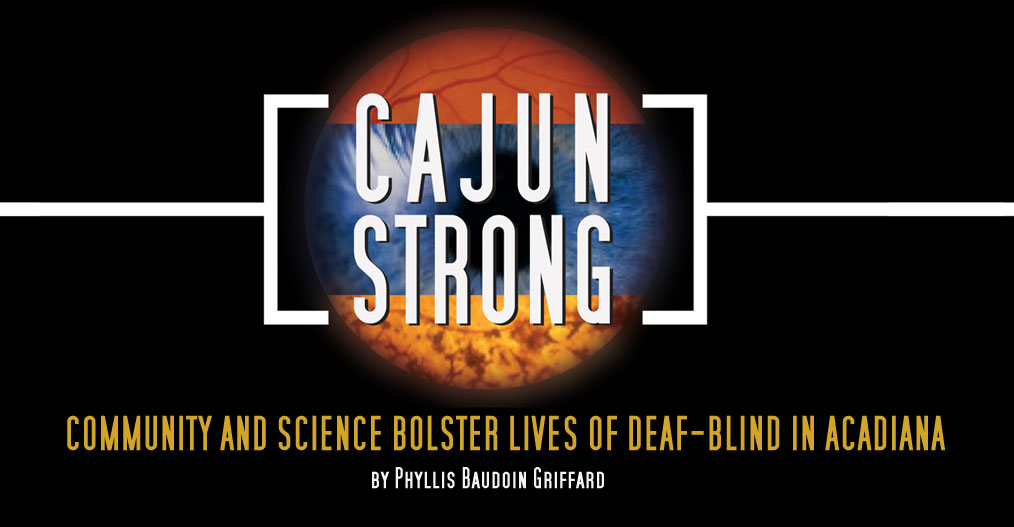

Usher syndrome is a recessive condition in which each child of two asymptomatic carriers has a 25 percent chance of having the condition. Many carriers are unaware of their genetic status. Image by Romy Mariano

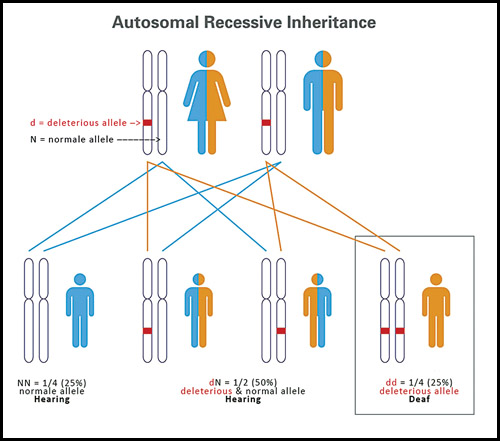

Left: Normal structure of rod cells of the retina. Center and right: Fluorescence-labeled cross sections of normal retina and those with advanced retinitis pigmentosa.. Courtesy of the American Foundation for the Blind

Today, parents of babies born profoundly deaf quickly realize they have difficult decisions to make about whether their child will inhabit the hearing world of cochlear implants, the Deaf world of ASL, or both. Most choose cochlear implants, even if the devices can relay only a subset of the frequencies that make up natural sound. This choice requires the family’s commitment to intensive speech therapy and educational intervention, which does not leave much time for the entire family to learn ASL. Deaf culture encourages families of deaf children to make this extra effort. Many Deaf are against implantation, in part out of concern that, for some individuals, implants do not allow full communication, whereas ASL does. The Deaf are in a fight to protect their language and culture, a struggle familiar to older Cajuns. Kaleb’s parents carefully considered the Deaf community’s antipathy for implants and participated fully in Deaf culture by learning and using sign language with Kaleb. It was a dog attack at age four, well before his Usher diagnosis, that finally made up their minds to have him receive implants. His mother Monica explained that even if cochlear implants would not make him a fully oral and hearing person, at least he would be able to communicate during an emergency. The Deaf can relate, as most have stories of being misunderstood in public or victimized by scams, or they know someone who was injured or killed as a pedestrian. In fact, Dan’s story of being abandoned overnight in Baton Rouge after an athletic event, where he was later found by police sleeping in a ditch, surely helped convince policy-makers that the deaf-blind desperately needed an SSP program.

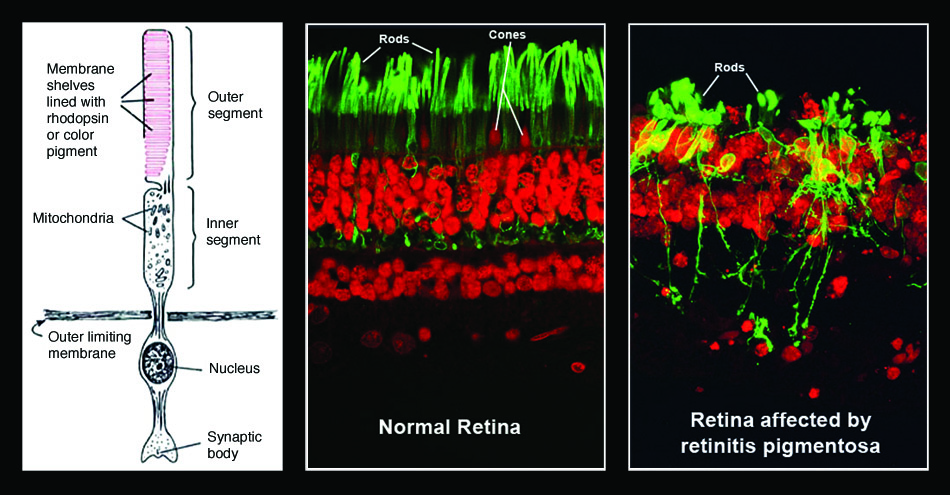

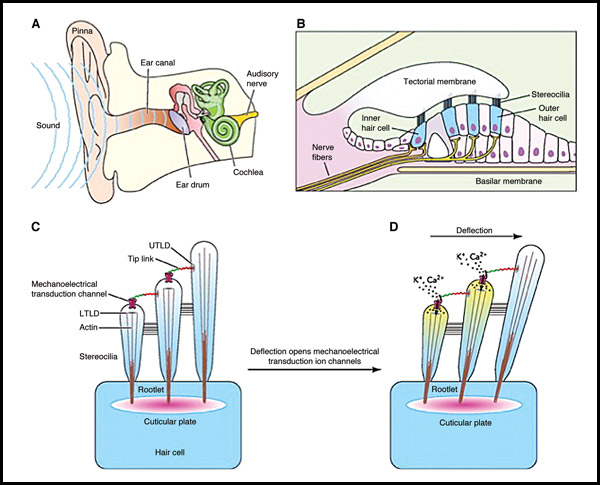

Normal hearing results when vibrations are transmitted through the ear to hair cells in the cochlea. The stereocilia on the hair cells are misformed in Usher syndrome due to a variation in the protein harmonin. Courtesy of Lifeng Pan and Mingjie Zhang

Tonight’s group is a small but representative subset of the deaf-blind Cajuns. No one seems to know exactly how large this population is, but estimates range from 200 to 2000. The higher estimates come from the deaf-blind community itself. Nancy O’Donnell, director of the USH Trust registry, estimates that 5 to 10 percent of deaf citizens have Usher syndrome; the logic follows that therefore at least 5 percent of the 20,000 deaf citizens in southwest Louisiana—1,000 people—have Usher syndrome. “The challenge is that different researchers suggest different numbers,” says O’Donnell. The USH Trust aims to identify all Usher citizens to better connect them to research, but fewer than fifty people from Louisiana have registered so far.

Because of advances in research and increased connections among Usher families, the youngest generation of Cajuns with Usher syndrome may be able to slow their vision loss. Dr. Jennifer Lentz now heads the Usher syndrome research group at the LSU Health Sciences Center where this research was pioneered during the 1970s. Hers is one in a network of research labs around the world working with the deaf-blind to understand the molecular basis of their condition. A breakthrough occurred in 2004 when Lentz inserted the exact Acadian Usher gene into mice. Like deaf-blind Cajuns, her mice are deaf, have balance problems, and experience deteriorating retinas. Understanding the DNA variant that creates the misinformed protein harmonin has illuminated the protein’s normal role in the inner ear and retina. Lentz has developed a gene therapy using anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASOs) that prevent deaf-blindness in her USH1C mice. The FDA has approved the use of ASOs to treat other human diseases, thus allowing Lentz to apply for human trials of the USH1C ASO. “The first trials would likely be conducted in adults with advanced blindness,” explains Lentz, conveying the importance of the deaf-blind community in this effort. Within a few months of the 2016 Usher Syndrome In Louisiana Symposium in Lafayette, Lentz was able to recruit deaf-blind adults for a new phase of her project, one that is studying possible interactions of USH1C with other genes to understand why some lose vision faster than others do. Some of these research participants are here tonight at Starbucks.

A sign across the street from the Affiliated Blind of Louisiana training center. Courtesy of Phyllis Griffard

The deaf/deaf-blind community in Acadiana is close-knit, but no longer isolated. Deaf-blind community members go to school, play sports, and run for class president. They fall in love, get married, raise children, and have meaningful careers. They cook, go to football games, renovate their homes, play bingo, boil crawfish, and worship together. They do more and more of this among the hearing. They do not lament their deafness, and generally accept their vision loss. They do not want pity; they want independence and a voice. They stay abreast of advocacy issues and are politically astute. They rallied in Baton Rouge in 2007 to get their SSP program, and made more trips to the capital this year to get it expanded. The conversations tonight are likely to be about all of the above.

After about an hour of socializing, Dan gets ready to say a few words. He stands, checks that he is facing the group, gets everyone’s attention, and makes sure that every deaf-blind participant has a tactile interpreter. He thanks everyone for coming, dramatizes what might be interpreted as a drum roll, and pulls a receipt from his stack with flourish. Annie reads it and spells the name of the winner of the door prize into Dan’s hand. The winner is me. After a bit of ASL/blind applause (hands waving and/or feet stomping), we take a group selfie that will end up on Facebook. The conversations continue until the group disperses over the course of the evening. We will be back again next month for more fellowship, news, coffee, and cake.

Phyllis Baudoin Griffard, PhD, is an award-winning biology educator on the faculty of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (ULL). She has launched OurBio, an education media initiative that connects local biology to history and culture. This article is a companion to a documentary film about the deaf-blind Cajuns produced in collaboration with Ms. Conni Castille, Director of Moving Image Arts at ULL.