Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers

New exhibition traces evolution of Black studio photography

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: February 28, 2023

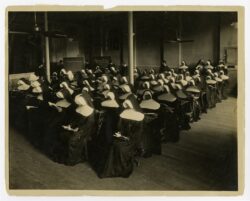

Xavier University of Louisiana, Archives & Special Collections

Arthur P. Bedou, Sisters of the Holy Family, Classroom Portrait, 1922. Gelatin silver print.

Visitors to the New Orleans Museum of Art will be able to see superlative works by Battey, Bedou, Scurlock, and over two dozen other artists in the exhibition Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers. Organized by NOMA, the exhibition focuses on the artistic virtuosity, social significance, and political impact of Black American photographers working in commercial portrait studios during photography’s first century and beyond. The exhibition explores how Black studio photographers worked in photographic media from its earliest introduction in the United States, as well as how their photographs are exemplary of important movements in art like pictorialism and modernism. Called to the Camera reframes the history of American photography by placing Black photographers and subjects at the center of that story.

This exhibition gathers over 175 vintage photographs, from the nineteenth century to the present, including those by the very first generation of Black American photographers, such as James Presley Ball and Alexander Thomas (born in Louisiana in 1826), as well as photographers who were active in the 1960s, like Rev. Henry Clay Anderson. Many of the photographs in Called to the Camera, like tintypes by the Goodridge Brothers Studio (1847–1922) and gelatin silver prints by the Hooks Brothers Studio (1907–79), will be on view for the very first time; some, like the 1855 daguerreotype portrait of Frederick Douglass, are one-of-a-kind. Because of the extremely light-sensitive nature of the material, some of these works will not be publicly displayed again for years to come. Demonstrating that the Black photography studio was truly a national phenomenon, the exhibition also includes an interspersed selection of works by modern and contemporary artists, illustrating connections between the historical legacy of Black photography studios and what we consider to be fine art photography today.

Called to the Camera includes a partial recreation of Addison Scurlock’s studio, based on a photograph he made in 1911. The immersive gallery mimics the experience of entering an early twentieth-century commercial studio, establishing a contextual framework for viewing the works on display. The installation includes a dense installation of portraits by more than a dozen photographers working around the country—from New York to Houston, and from Oakland to Columbia, South Carolina. The exhibition then breaks into a number of focused presentations centered on particular studios, including some well-known names like James Van Der Zee, and less widely known figures like Austin Hansen. Alongside Bedou and Thomas, the exhibition includes work by Louisiana photographers Florestine Perrault Collins, Arthur Perrault, Villard Paddio, and Nolan Marshall Sr. At several points, Called to the Camera includes business documents, letters, advertisements, and studio elements, visually demonstrating the day-to-day work of the Black studio photographers. The exhibition also turns outward from the photography studio proper to genres like photojournalism and commercial photography, illustrating that the business conducted inside the studio could be considered the center of what was often a much broader photographic practice.

Objects on view in the exhibition have been lent by a number of important national collections, including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Library of Congress, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as important institutions closer to home, including Xavier University of Louisiana Library and Archives and The Historic New Orleans Collection. In addition, Called to the Camera constitutes the first showing of important recent additions to NOMA’s permanent collection, including work by Eric Waters, Endia Beal, Tiffany Smith, and Polo Silk.

Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers is on view at NOMA through January 8, 2023. A catalogue accompanying the exhibition will be distributed by Yale University Press.