Cane Contemplations

Sweetening the present, remembering the past

Published: March 1, 2021

Last Updated: June 8, 2021

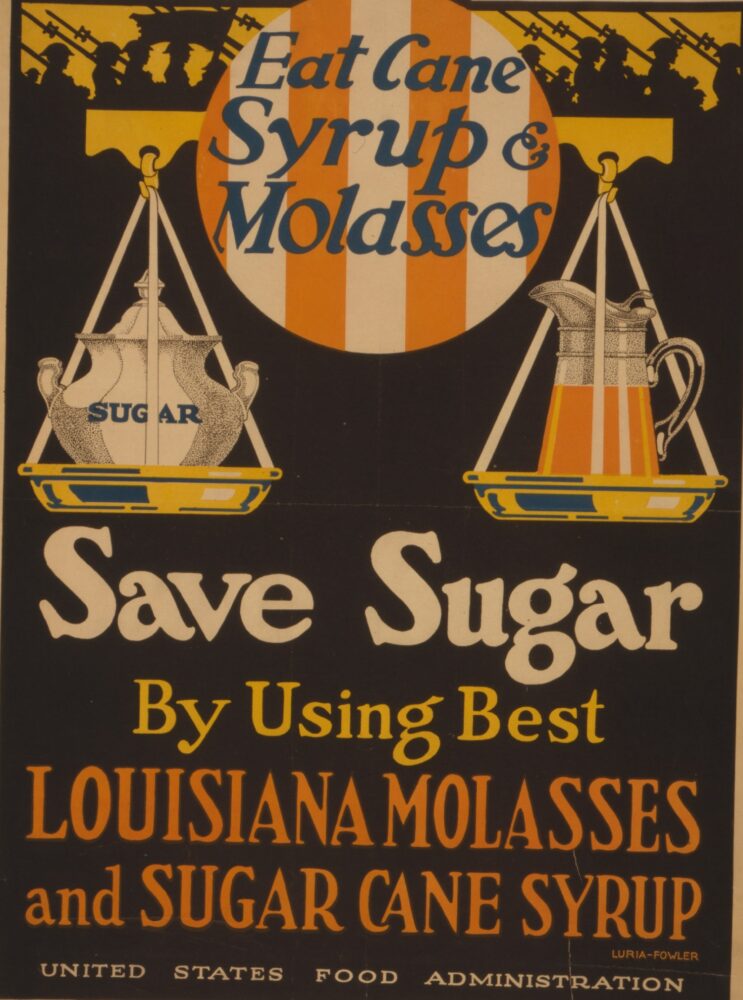

Library of Congress

A World War II rationing poster exhorts Americans to eat cane syrup and molasses, saving sugar for the front lines.

There are railway cars overflowing with stalks arriving at the sidings in Enterprise, Louisiana, and the air is thick with the heavy, sweetish smell of burning bagasse, or cane trash. It’s that time of year again, and cane is being transformed into sugar. The mills are running day and night as they work to process the tons of cane that are expected to pass into its giant maw. Mountains of raw sugar in the warehouses dwarf the trucks that navigate between them. In sugar processing season, spanning October to January, the mills run twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, as the centuries-old ritual takes place.

Enterprise, Louisiana, is the home of Enterprise Plantation, established by Pierre Simeon Patout in 1825. The plantation was originally intended to be a vineyard, but Patout soon learned that the way to fortune in southern Louisiana was not through grapes but through sugar cane. And almost two centuries later, Enterprise is the oldest complete working sugar plantation in the United States. I made my first visit to Enterprise Plantation in 2012 with Peter Patout, New Orleans antique dealer and descendant of Pierre Simeon Patout. There, with my jewelry removed and hard hat donned, walking carefully between gears and chugging machinery, I watched as the raw cane was fed into grinders and followed the process along the line all the way to its conclusion in an adjacent warehouse.

Cane, although now fully at home in the southern part of the state, has only been grown in Louisiana since 1751, when it was introduced by the Jesuits. Early colonists cultivated creole cane, a type of cane that was not well suited to the Louisiana terrain and could not become a financially viable crop. Étienne de Boré became the first Louisianan to create wealth from the sugar-bearing reed, having learned how to produce granulated sugar in 1795 from two enslaved Cubans known only as Mendez and Lopez.

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, the exodus of planters from Saint–Domingue fleeing the unrest that signaled the coming of the Haitian Revolution brought other cultivars with them. Cane finally became an important crop in 1817, when ribbon cane was introduced. By the mid-nineteenth century, cane began to take off in southern Louisiana, and during the antebellum period almost all of the cane consumed in the United States came from Louisiana. Technological innovations like the vacuum pan evaporator invented by Norbert Rillieux outmoded the slower and more dangerous Jamaican Train method of processing cane into sugar and made Louisiana’s sugar even more profitable. The state became the sugar capital of the United States, a role it still holds.

The story of sugar cane is fascinating as it encapsulates much of the story of the Western hemisphere, with all of its messiness. As science writer Peter Macinnis explains in his work, Bittersweet, sugar’s voyage around the world brought with it four curses:

- Sugar cane is capital intensive and it requires large amounts of money to establish large plantations.

- Sugar cane requires immediate processing when ready for harvest as it deteriorates rapidly.

- Sugar production consumes enormous amounts of fuel.

- Sugar production is labor intensive and therefore the growth of sugar meant the growth ofenslavement.

All of the curses were evidenced in southern Louisiana. Most, though, have been attenuated or resolved over time, and agronomists and scientists are working to find creative solutions to those that remain.

The harvest is always a heady moment in cane country. In southern Louisiana, it coincides with the end–of–year holidays and has an almost festive air. As Peter Patout put it, “When the mills are going full throttle, it’s a very exciting time with its familiar smell and the cacophony of thrumming motors that fills the air day and night.” Indeed, the smells and sounds of the harvest are potent reminders of southern Louisiana’s close connection to the Caribbean region.

Pierre Simeon Patout’s mill at Enterprise has been chugging away for almost two centuries. Peter Patout celebrates his connection to it every year with his Christmas gift to friends: a simple brown paper bag tied with cord. Inside, there are a few pounds of dense, molasses-rich Louisiana raw sugar. It’s a perfect way to sweeten the present while remembering the past.

Jessica B. Harris is the author, editor, or translator of eighteen books, including twelve cookbooks documenting the foodways of the African Diaspora. In March of 2020, she became a James Beard Lifetime Achievement awardee.