Summer 1995

Catching Rats

Memories of the Louisiana fur trade

Published: May 14, 2021

Last Updated: May 28, 2021

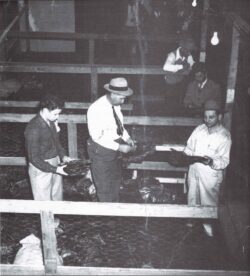

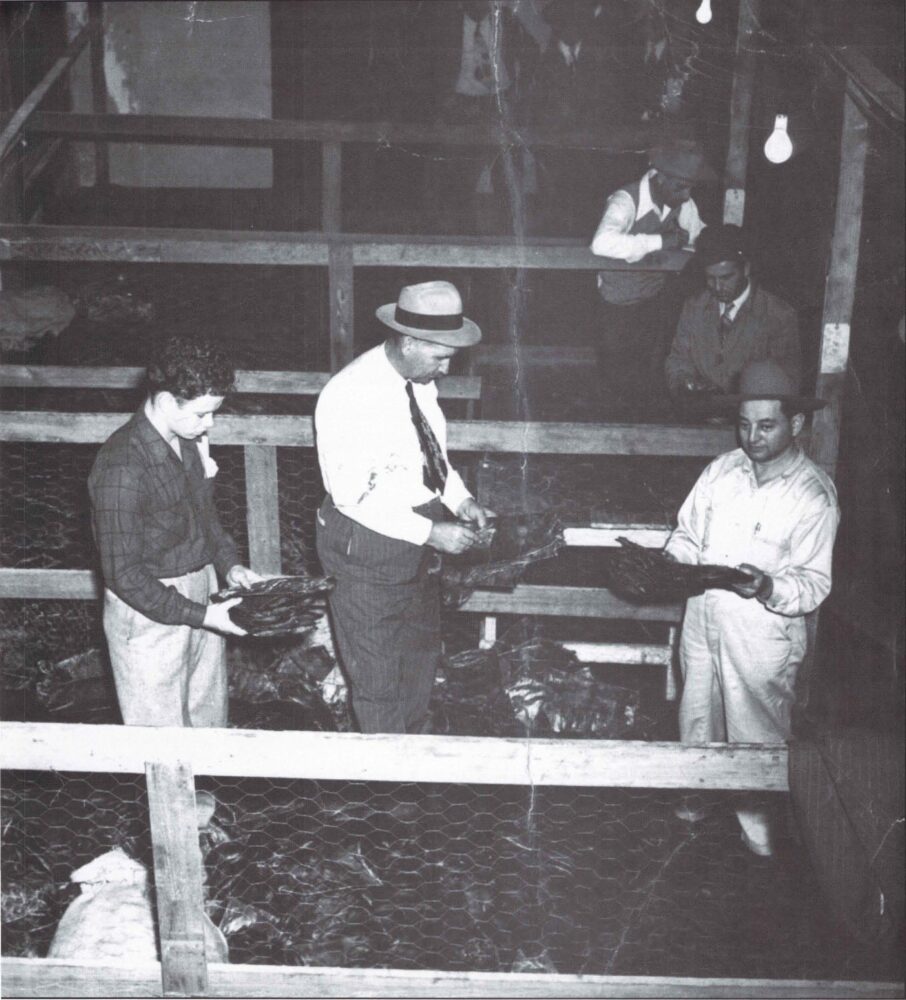

Percy Rodriguez, center, grading muskrat furs.

MaMa’ always cooked something good, and sometimes she slipped us a little extra pocket change for a treat. Both MaMa’ and PaPa’ spoke English with a thick Cajun accent, remnants of their upbringing along Bayou Lafourche, and when conversation turned to a more serious or private nature, they lapsed into the comfortable French dialect that was the first language of their childhood. This offered them the convenience of carrying on conversations in our presence that were not meant for our ears. I could never understand how my mother and her sisters could easily understand MaMa’s French and yet be unable to speak it. We accepted the linguistic inconsistencies that existed, but were incapable of comprehending their impact; we were witnessing the Cajun language losing its foothold, but were too much a part of it to see its value.

The Rat Car

PaPa’ liked to get an early start in the morning. Our territory ranged from the marshes in lower St. Bernard to Terrebonne Parish. We would spend days in places with names like Delacroix Island, Yscloskey, Venice, Reggio, Golden Meadow, Cut Off, or Bayou DuLarge. My favorite trips were to Houma or down Bayou Lafourche, and it was an adventure to leave early. We would start before dawn, at four or five. On cold days, we splashed warm water on the windshield of the car to dissolve the frost. The “rat car,” as we called it, was a dark blue ‘51 Ford. I didn’t know what color it really was until PaPa’ conned me into washing and Simonizing it with the promise of a driving lesson, saying that it was too dirty to use at the time . I spent the whole day trans forming the dusty, apparently flat-black car into a shiny dark blue one capable of being used to educate a student driver. No amount of washing and polishing, however, could remove the musky smell of hundreds of thousands of muskrat, nutria, mink, otter, and occasionally, raccoon hides.

The primary function of the rat car was to haul furs. There was no heater in the car, so we draped an old blanket over our laps for warmth. The first stop was breakfast, some times at Morning Call in the French Market. At five in the morning, everyone there was either going out or coming in. Weary women and men returning from a night’s work doing what ever people did at night in the French Quarter, eager fishermen, an occasional wino in the corner, and PaPa and I would sit in silence, sip-ping the rich Cafe’ au lait and nibbling hot powdery beignets.

No amount of washing and polishing, however, could remove the musky smell of hundreds of thousands of muskrat, nutria, mink, otter, and occasionally, raccoon hides.

Sometimes PaPa’ would wait until after we crossed the Huey P. Long Bridge to stop for breakfast at a place in Paradis on Highway 90. There, he would always order the same thing, in the same way: two eggs over easy and a cup of pure coffee . When ordering, his Cajun blood forced him to say it with his hands as well as his mouth. He would start with his palm turned upward, slowly roll it over until it was turned downward, and gently allow it to descend towards the table as he pronounced “ooover eeeasy.”

We rode most of the way in silence. We would travel down Highway 90 through Paradis, Boutte, and Des Allemands. As we traveled down the two-lane highway towards Raceland, the sun would peek up over my left shoulder, and PaPa’ would always say the same thing: ”Old Sol’s peeking his eye out.” We would pass spots in the road that bordered the marsh where we could see duck blinds from the road. Occasionally, from within the con fines of the rat car, we could hear the muffled “poof” of a shotgun being fired from a distance over the chilly marsh. PaPa’ would tell me stories of how, when he was a boy, the sky would turn black with flying ducks. As we approached Raceland, we would see sugar cane fields sur rounding a large mill. At the cross roads of Raceland, we either continued to Houma or turned south and head ed “down the Bayou” on Louisiana Highway 1 towards Golden Meadow. As we drove along and passed a church, PaPa’ would show his respect, not by making the sign of the cross, as was the custom, but instead by tipping the fedora he always wore. I don’t know if he wore the same hat year after year or he had a series of them . It always looked the same to me.

Trapping on the Bayou

As we traveled along Bayou Lafourche, we would stop at the occasional trapper’s house where weeks of work had accumulated in the form of dried muskrat skins. The trappers set the spring-loaded Victory brand traps in the marsh at spots they knew the muskrats would frequent. they would collect their catch by trudging through the marsh in hip boots and placing the carcass es of the trapped rats in a large can vas backpack. The rats were then skinned, the trappers slitting the skins from the tail down to the back legs. The skin was then peeled from the rat’s body and passed through an old-time hand crank washing machine wringer with wooden rollers, commonly called a “rat drier.” The skins were then placed inside-out on a triangular wire rack to stretch them out. The trapper would remove any excess flesh from the skin with a sharp pocket knife and hang the skins on a clothesline to dry. When dry, the skins were stiff, and the rack was removed. The dried skins, about the size of a sheet of paper , would be stuffed into a burlap sack and kept, until PaPa’ came along with enough money to outbid the competition and buy the hides.

Buying the furs from the trapper was a ritual. It all began in a room in the trapper’s house, the furniture pushed aside to allow a big open space in the center of the room. A chair was usually supplied for PaPa’, and he occupied it like a throne. The trapper would pile sacks of furs near the chair, and from that point on, there was no conversation. Everyone worked in silence, and everyone knew his job. PaPa’ assumed his grading posture, sitting there in his fedora with the omnipresent cigar sticking out of the corner of his mouth. He would reach into the open sack, remove one of the stiffened skins, grasp the wide end, pry it open so he could see the fur on the inside to determine its quality, and then toss the skin to a spot on the floor. As he worked through the sacks, he would toss the hides like a dealer tosses cards. The rats were dealt out to the various stacks depending on the quality of the fur. PaPa knew how much he could offer for each fur, and the price was set according to the grade.

Here, PaPa’ had to walk a tight trope . If he graded the furs too leniently, he would make the company he represented, Marindona Brothers, unhappy. If he was too stringent , and offered too little, the trapper would sell to the competition. All of this must have gone through PaPa’s mind as he deftly handled and tossed out each skin. Enhancing the intensity of the deal was the knowledge that many of the trappers were relatives or family friends, or compatriots of PaPa’ him self. After all, he was raised along Bayou Lafourche, and married MaMa’, who had nine sisters, all of whom had families of varying sizes. People with names like Cheramie and Savoie were all kin.

As a young man, PaPa’ moved his family to Delacroix Island, operated a barber shop, and bought furs during the winter months. PaPa’ had been a trapper himself, and he understood what these men had to go through to get the furs. He understood the hard lives they led. They respected and trusted him, and he developed a close bond with many of them in the forty years they did business.

The room would remain quiet except for the swishing sound of the dried muskrat skins sliding across the linoleum. The room was usually warmed by a butane space heater, and carried a slightly musky, not unpleasant smell from the hides. My job was to move from stack to stack and count the skins, laying them in alternating stacks of ten. They were cross stacked into stacks of a hundred. Counting was an important job. The number of each grade determined the final offer. I scurried between the stacks on my knees.

PaPa’ would remove the cigar from his mouth just long enough to shove in the crackers and Vienna sausage while he visited with his sister.

The trapper sat quietly observing PaPa’s actions, hoping for a good price. When the last rat was graded, he would pull out an old green pocket notebook and a stub of pencil. He would point to each stack and I would give him the count.

For the next few minutes, the silence in the room was absolute. I observed the ritual many times, PaPa’ hunched over the notebook, chewing on the cigar as he ciphered. After the figuring was done, he would announce the price to the anxious trapper. Invariably, they would sit with their elbows on their knees and gaze at the floor while considering the offer . Sometimes they would whistle softly and tap their feet rhythmically on the floor. I could almost see the thoughts going through their minds. How hard they had worked, whether or not they wanted to get more bids from the competition , or whether they graded the skins thoroughly. Or they might be weighing if they set high enough the price that was placed on hours sloshing through the marshes, fighting the chill when it was cold and the mosquitoes when it was hot, to work for their families. Sometimes, they would think for such a long time that PaPa’ had to gently prod them for an answer. Finally, with a nod and an “OK, Mr. Percy,” the deal was done.

PaPa always carried a big wad of cash in his pocket. The trappers weren’t interested in checks. There wasn’t any place nearby to cash a check, and they didn’t want their simple lives complicated by the intricacies of modern finance . When the deal was finally sealed and the cash passed over, I would swing into action. I went out to the rat car and grabbed several of the big burlap sacks from the floor in the back. From inside the glove compartment I would grab several lengths of loose cotton twine and a big, curved sewing needle several inches long with an eye big enough to accept the twine. We would stuff the furs into the sacks and sew the ends shut. I would then haul the sacks out to the car and load them up, starting in the trunk, and then filling the cavernous void in the rear of the rat car that, under ordinary circumstances , would have been the back seat. On a good day, the car would be so full we couldn’t see out the back window.

Comfort in Community

We would usually toil until lunch, which came at various times depending on where we were in the course of the day’s work. Sometimes we were invited to eat at someone’s house. In the Cajun homes, the kitchen was the heart of the house . I remember board walls painted cheerful colors; a steamed, paned-glass window reflecting the gray winter weather that was such a contrast to the warmth inside; religious icons on the walls; and porcelain-topped tables with white legs and black trim, and leaves that slid out from under the table top to make it large enough to accommodate big families. The kitchen was where you visited, ate, and generally spent most of your time. The food was prepared by women who moved about the kitchen with absolute confidence in the knowledge that this was their turf, and, in the heart of the house, they were its lifeblood. The food was always good. One time, everyone was raving about a particularly good jambalaya . I was just a little kid at the time, and I recall that it was good, but it couldn’t touch my mother’s. My mom cooked a world-class jambalaya, the kind you could hurt yourself eating.

Sometimes we stopped and ate at the Hubba Hubba Club. I don’t recall exactly where it was; maybe Raceland. The meat there was tough, but PaPa’ said that chewing tough meat was good for your teeth. MaMa’ would always ask us where we ate. When we told her the Hubba Hubba Club, she always shot out the same line: “I think your PaPa’s got a girlfriend at the ‘Ubba ‘Ubba Club.” MaMa’ couldn’t pronounce the letter “H” to save her soul. Her accent was too thick.

When we were buying rats at Delacroix, we would stop and visit PaPa’s sister, my Aunt Annie. She and her husband owned Mack Melerine’s boat launch on Bayou Terre aux Boeuf. We would stop at the grocery store and buy bread, lunch meat, a pack of Klotz crackers and Vienna sausage. We would go to the bar that Uncle Mark owned across the road from the launch; I would make sandwiches, and PaPa’ would remove the cigar from his mouth just long enough to shove in the crackers and Vienna sausage while he visited with his sister.

Delacroix was a very tightly-knit community. Everyone there knew PaPa’ and everyone knew my mother. They always nodded to me and asked, “That your boy, Percy?” PaPa’ would reply, “No, he’s my grandson. He’s Joyce’s boy.” They all knew Joyce, so there was no further need to direct any conversation towards me as my identity had been established.

We would ride home, usually in silence, myself tired, staring at the stained legs of my pants, oily from the thousands of pelts lifted, stacked, and carried during the day. We would go home and haul the sacks into the house for safekeeping. Sometimes we would stop at Marindona Brothers on Decatur Street near Jax Brewery. I didn’t like going there because PaPa’ was obligated to give a full report of the day’s activities to whatever Mr. Marindona was at the office while they sipped glasses of Scotch and water. It was usually late in the day, around dark, and I would be very tired, too tired to have to sit quietly in the outer office while the men talked business. The office was one of those old-time models with high ceilings, a big clock on the wall, and a fancy wooden railing with a swinging gate, like the ones seen in courtrooms, that separated the inner from the outer offices.

I was glad when we finally got home. MaMa’ was there to quiz us thoroughly on where we went and who we saw. It was always good to get a hot bath, eat a good meal, and collect the fruit of the day’s labor: five dollars.

Considering the work I did and the time I spent, five dollars was a paltry sum even for that day and time . We all did it, my brothers, myself, and my cousins. We enjoyed it. We still talk about it. We did a lot and learned a lot about who we are. We travelled all over the part of the state where muskrats and muskrat trappers lived. We travelled on gravel roads and walked into houses that had elevated boardwalks leading to the front doors instead of sidewalks. We drank strong coffee made in little porcelain pots with a sack inside that looked like a sock, coffee brewed with water collected from people’s roofs into large cypress cisterns. We listened to radio news broadcasts given in both English and French because a lot of the listeners still didn’t speak English; others had had the French “educated” out of them by unenlightened school teachers . At Delacroix, we saw both sides of the bayou lined with moss-draped oak trees where there’s nothing but grassy march now, and we went into the houses that later floated away in Hurricane Betsy. We tasted the food and saw the sights along lightly-trafficked two-lane highways. We were witness to and part of a way of life that was disappearing like the marshes, the muskrats, and the language. We enjoyed the nice feeling of riding down the road quietly with PaPa in the rat car. What a deal. The five bucks was lagniappe.

Bryan Gowland is a school teacher and mayor of Abita Springs, Louisiana. He is also the host of the LEH-funded Piney Woods Opry, the old-time radio country music show.