Magazine

Channeling the Master Plan

The science behind saving southwest Louisiana’s working coast.

Published: June 1, 2017

Last Updated: July 4, 2019

Edmund Fountain

The Yasa Golden Bosphorus, a 61,342 ton crude oil tanker, makes its way northward in the Calcasieu Shipping Channel on April 12, 2017.

“The sun is shining. No clouds in the sky. There’s a gentle breeze. And the operating draft on the channel is forty feet. So I’m happy,” said Hayden, who makes sure that deep-water vessels—barges, ocean-going vessels, smaller boats—move steadily along the sixty-eight-mile Calcasieu Ship Channel, which connects the Gulf of Mexico and the Port of Lake Charles. Ships first turn into the channel in the open sea,thirty-two miles off shore. As they travel to shore, the channel is bounded by two lines of pylons, red on the starboard side and green on port.

Those ships coming from the Gulf are boarded off-shore by a Lake Charles pilot, who then steers them through the “inside channel”—thirty-six additional miles of waterway, dug forty feet deep, four hundred feet wide, that heads north to the Port of Lake Charles. From the port, cargo is delivered to a cluster of nearby refineries and factories or shipped across the country by pipeline, rail, and truck.

Courtesy of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority

Hayden, the head of navigation and security for the Lake Charles Harbor and Terminal District, is proud about his role in what is now the nation’s eleventh-busiest port and one of the nation’s leading petrochemical hubs. The port has grown tremendously in recent years because of its ability to handle liquified natural gas. Forecasts of traffic in the channel predict an increase of 50 percent over the next five years and by 100 percent by 2023, doubling current levels.

The port leaves a sizeable footprint in southwest Louisiana, said Hayden, citing an economic-impact study that his board commissioned two years ago. “Out of every dollar in the pockets of people in the Lake Charles metro area, forty-six cents comes from the ship channel,” he said. Ships bring in crude oil and carry out Louisiana rice along with gasoline, heating oil, and petroleum-coke powder to fuel blast furnaces. Oil companies also rely upon barite shipped in from China and India to be ground into powder in Louisiana, then mixed with mud to weigh it down as new wells are drilled.

Yet, as with Louisiana’s other manmade navigation channels, economic boon sometimes comes with environmental cost. Created from the Calcasieu River, Hayden’s north–south ship channel, especially when combined with the east–west Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and the nearby Sabine–Neches Waterway, has changed the way that water moves within the Chenier Plain. The waterways interrupt the natural flow of freshwater across the area, and together they serve as conduits that bring saltwater and hurricane storm surges deep inland, exacerbating flooding and land loss, as well as degrading freshwater marshland, fisheries, and wildlife habitat.

A nearly $450 million project is now underway with plans of cordoning off this economic artery so that it bleeds less saltwater into the surrounding marsh. According to current timelines, the project should be complete by 2022, just as the port’s traffic is doubling from current counts.

Some worry that project’s completion, combined with the rapid increase in traffic, may give port officials a reason to propose deepening the channel even further, to fifty feet, as other channels have done in recent years.

That’s partly a concern because it’s taken so long to get this project off the drawing board. State-created plans for the past few decades have documented the effects of saltwater intrusion from the channel, but little came from those plans, said coastal scientist Denise Reed, Vice President for Strategic Research Initiatives of The Water Institute of the Gulf. “The project is now moving forward and it will have great benefits,” Reed said. “But because twenty years have passed, we have a greater problem to deal with than if we had acted sooner.”

In 1994, a national “action agenda” on coastal and shoreline erosion published by the federal Environmental Protection Agency described the damage wreaked by the three waterways. “The hydrology and saltwater regime of this basin were radically altered,” the report noted, with a suggestion that barriers be put in place to protect against the encroaching salt water.

Across coastal Louisiana, the scenario has been duplicated by larger navigation channels like that in Calcasieu and by the network of relatively unregulated channels used for oil and gas extraction. “If you worked really hard to mess up the hydrology of south Louisiana, you couldn’t have done much worse than our forefathers did,” said David Richard, a biologist and longtime resident of the area who now works for Stream Wetland Services, managing land and working for private industry using dredged material to restore marsh. Part of the problem, Richard said, is that, historically, wetlands were seen as wastelands, a view that did not account for estuaries’ crucial roles as natural hurricane protection, filters for pollutants, nurseries for fish and seafood, and stopovers for migratory waterfowl.

In recent years, officials in the area have worked to construct some small barriers near the channel. But to deal with the ship channel’s incoming flow of saltwater required salinity control of a different magnitude. And several years ago, that big idea got its first big break in the Coastal Master Plan, thanks to the coastal scientists and engineers at the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), who looked at salinity control for the channel and deemed that it should be considered a high-priority project in the state’s 2012 plan.

“We’re behind the eight ball, completely behind the eight ball. And we say that in public meetings on a regular basis. Because we know that the cavalry is not coming. We have to do this ourselves.” Nedra Davis

Since then, Reed and her colleagues at The Water Institute have provided key analysis on the project, formally called “Calcasieu Ship Channel Salinity Control Measures,” which is now in an engineering and design phase. Models suggest that the project could retain up to forty thousand acres of marsh that would otherwise be lost in the Calcasieu–Sabine Basin in the next fifty years. An added shoreline protection project stretching from Freshwater Bayou to Southwest Pass will help maintain the shoreline in the southeast corner of the Chenier Plain.

For people who live and work in southwest Louisiana, the project’s high ranking felt long overdue. Lake Charles is the fifth-largest city in Louisiana, but sometimes, they say, given its sleepy rural setting and its location near the Texas border, Lake Charles seems easily forgotten.

By comparison, metropolitan New Orleans and the Mississippi delta get a disproportionate level of attention, said Nedra Davis of the Chenier Plain Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority, which champions projects in Calcasieu, Cameron, and Vermilion Parishes. Calculations of landmass and people show that these three parishes have roughly 3 percent of the population density of Orleans Parish. This semi-isolated region isn’t often a priority for public officials, Richard said. “It comes down to numbers and voters. And southwest Louisiana simply doesn’t have enough voters over here. So we have been overlooked.”

Davis, a project manager in engineering who did storm-surge modeling at Louisiana State University for thirteen years, said that officials in the three parishes have largely realized that they can’t wait for anyone else to stabilize their region’s crumbling marshland. While this bigger project is moving forward, officials in this area are working to finance smaller salinity barriers, rebuild beaches, and protect crucial areas of shoreline, though they are hampered by state laws that don’t yet allow the region’s newly formed levee district to levy millages without voter approval.

“We’re behind the eight ball, completely behind the eight ball. And we say that in public meetings on a regular basis,” Davis said. “Because we know that the cavalry is not coming. We have to do this ourselves.”

Coastal researcher Don Davis devotes an entire chapter to the longtime residents of the Chenier Plain in his exhaustive book, Washed Away?: The Invisible People of Louisiana’s Wetlands. “It’s cattle country—the last major cattle drive in the country was there,” Davis said in a recent interview. “People there have crossed over everyone’s land. Some people have been attached to the same land for two hundred years, back before the Louisiana Purchase. Those folks are just anchored in place.”

In some areas in southwest Louisiana, cattle paths are still visible between the cheniers—raised ridges often covered by stands of oaks—that run parallel to the Gulf shoreline. They’re a defining characteristic of the landscape on southwest Louisiana’s Chenier Plain, which is considered its own region, geologically distinct from the bird’s-foot delta region in southeast Louisiana.

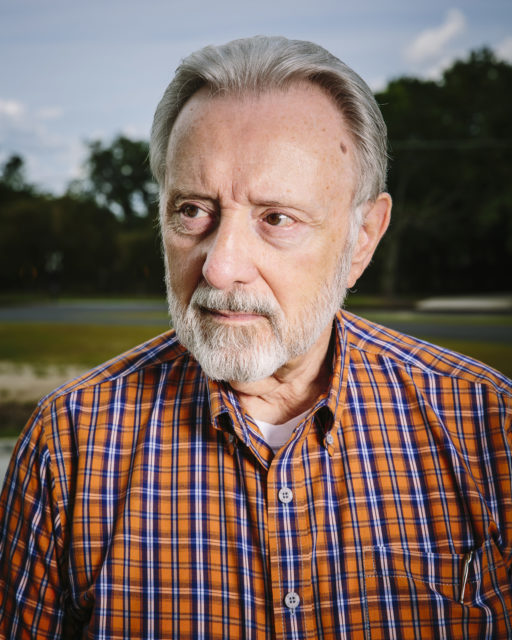

Channing Hayden, the head of navigation and security for the Lake Charles Harbor and Terminal District. Photo by Edmund Fountain

The chenier ridges, which can rise ten feet above the marsh, are abandoned deltas left behind by a shifting Mississippi River and other streams that formed a series of parallel beach lines by the Gulf of Mexico. The most northern ridges likely were active shorelines 2,800 years ago, while those closest to the Gulf are more recent, dating to 1,100 years ago. Between the ridges are wide expanses of marsh.

Of course, the landscape for Chenier Plain cowboys was always damp and swampy. Don Davis described Louisiana cowboys speaking a French patois who attached spurs to rubber boots, because that’s what worked best in this climate. Chenier Plain cattle drives also frequently used boats to float the cows to market, Davis noted, and everyone’s cows grazed together on saw grass in the area’s swamps in the winter.

Yet historical clues show that the swamps, bayous, and lakes were much fresher then. Some were even lined with cypress, until salt levels got too high, killing the trees. Around the turn of the twentieth century, water from the lake was regularly used to irrigate fields of rice, a crop that can’t tolerate even low levels of salinity. Saw grass, the native plant on which the Chenier Plain cattle grazed, is intolerant of salt but flourishes in freshwater or intermediate marshes. A 1951 Soil Conservation Service map documenting vegetation showed that much of the area was covered by the plant. In the late 1950s, a massive storm surge from Hurricane Audrey was followed by a drought that raised salinities even more than usual. By 1962, nearly all of the saw grass was dead.

As a result, everyday life is different for longtime residents who grew up fishing, hunting, and playing in the swamps, said David Richard, whose ancestors date back to about 1850 in this part of Louisiana. Kids today growing up in the Chenier Plain are not likely to see frogs, alligators, and the wide variety of birds he grew up seeing in freshwater, intermediate, and brackish marshes during his childhood, he said. That’s because freshwater marshes rely on detritus and decaying organic material, he said, a process interrupted by saltwater intrusion, which washes all of the detritus to sea, turning the marsh into open water.

Because Louisiana contains 35 percent of the nation’s freshwater wetlands, its increasing losses are also the nation’s loss. “Without enough freshwater marsh, children today might not be able to chase a frog or pick up a turtle. They won’t catch a bass or a white perch,” said Richard, who worked for the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries for sixteen years, banding every brown pelican that came into the state and doing bald-eagle surveys of mating pairs. He saw abandoned bald-eagle nests in groves of cypress killed by similar surges in salinity near the Houma Navigation Channel. “Those trees are never coming back,” Richard said. “And we can’t bring back the diversity of the marshes to what they were historically. But this project is important, because it may allow us to bring some marshes back and to find a way to live symbiotically with commerce.”

Feldbaum is the project manager for the salinity control project at CPRA, which was created by the Louisiana legislature after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita devastated parts of the state in 2005. Through its Coastal Master Plan, updated every five years, CPRA’s scientists and engineers are tasked with creating a big-picture vision for a sustainable Louisiana coast, then guiding and coordinating efforts to protect and restore the coast at all levels: parish, regional, state, and federal.

Since the first Master Plan was completed in 2007, 135 projects have been completed or funded, improving 275 miles of levees and 50 miles of barriers island. The result will restore and protect 31,000 acres of land. But all of those projects started as a mention in the Master Plan, which is basically a coastal to-do list for the next fifty years. Feldbaum likes to compare the first steps of this process to satellite imagery, taken a few miles above the planet. To make it into the state’s Master Plan, he said, all CPRA needed to know was that controlling salinity in the Calcasieu Ship Channel would have positive benefits in the future.

It helps if the project has already been evaluated by someone else, said Brian Lezina, who works with Feldbaum in CPRA’s planning and research division. In this case, the ship channel was being studied by the US Army Corps of Engineers, whose staff told CPRA that the Corps didn’t have the time or budget to study the salinity control project with the sort of detail it required. But the Corps recommended it for further study. CPRA analysts looked at the project more closely and concluded that it should be labeled “high priority” in the 2012 Master Plan and that money should be set aside for a feasibility study.

Using Feldbaum’s analogy, that step zoomed in further on the project, taking it from a satellite image to, say, an aerial image, taken from an airplane, he said. During the feasibility study, Feldbaum and his co-workers were tasked with considering all alternatives that could meet the ultimate goal of the project, which was curtailing the amount of salt that came in from the Gulf to reduce wetland loss in the surrounding Chenier Plain region.

Austin Feldman,project manager for the salinity control project at CPRA. Photo by Edmund Fountain

They considered dozens of different structures that could limit saltwater intrusion, conducted technical and engineering analyses of each, and compared costs and benefits. Some of the concepts proposed would have been located at the mouth of the channel, where it meets the Gulf. Feldbaum and his co-workers studied a single-barrier sector gate, a lock, or pass-through gates there. They looked at perimeter control, where barriers would be placed at every opening that connects with the channel. And finally, they examined the concept of isolating the channel through berms built at the edge of the lower channel, where it cuts through Calcasieu Lake. Ultimately, this idea, which also included periodic gaps in the berms to allow fish and boats to pass through as they traveled the lake, would be chosen as what CPRA calls a “tentatively selected plan.”

The project was then sent to scientists at The Water Institute, the independent research nonprofit formed in 2011 to help coastal communities solve environmental challenges. Ehab Meselhe, a civil engineer who directs natural-systems modeling for The Water Institute, was part of a team selected to do further analysis on the Calcasieu Ship Channel project. His team ran each of the proposed concepts through a modeling process and ranked them according to benefits, obstacles, costs, and construction time, along with projections of how each concept would affect the channel’s salinity control, land loss, flood protection, navigation, and sedimentation.

By the time the salinity-control project made it to stakeholder meetings with parish officials and area residents, CPRA had already put the project through several steps. CPRA staff had introduced a range of viable solutions and The Water Institute had run each concept through its modeling process. Hayden, who was part of a navigation focus group, told CPRA’s project team why he opposed using gates across the channel to block the incoming tide. “Since the channel is only authorized to be forty feet deep, we use the tide to move heavily loaded ships,” he said, explaining how the tide causes the water in the channel to rise to about forty-four feet, which allows ships loaded to forty feet in depth to move through the channel with extra under-keel clearance between them and the channel floor. To close the gate when the tide was coming in would have “severely hampered” navigation, he said. Plus, the gates would have been held in place by a structure that spanned the width of the muddy channel’s floor. “Right now, we have a very soft and forgiving bottom, so if a ship runs aground, nothing will puncture it,” he said. In the end, after months of meetings, Hayden said, they reached the current design, the earthen barrier that separates the ship channel from Calcasieu Lake.

There’s a dual benefit, because channel operators can build up the new project’s berms with the four million cubic yards of sediment that the Port of Lake Charles dredges every year to keep the ship channel clear. The Army Corps requires federal navigation channel operators to dispose of dredged sediment in the closest and cheapest way possible; usually this results in sediment piled at the water’s edge. That expediency creates a hurdle for those who want to use all dredged sediment to rebuild the degraded marshes. In recent years agency partnerships have occasionally worked around the Corps’ requirements. In 2014 alone, thanks to additional funding, the channel was able to pump one million cubic yards of sediment—“a helluva lot of mud,” Hayden said—a few miles west, into the Sabine National Wildlife Refuge.

Hayden believes that, in addition to reducing salinity, the salinity control project will also make life more peaceful for commercial and recreational users of the lake, who will no longer be affected by “mini-tsunamis” created by channel vessels. “If a ship is sixty dead-weight tons, it pushes that amount of water out of the way as it moves,” he explained. “And so when that ship moves into the lake, boats there start rocking and rolling, because of the pressure waves that the ship throws.”

Last year, after each stakeholder meeting, Meselhe and his team headed back to their computers, using what they’d heard to better estimate impacts on vessel traffic and on people who work with shrimp, crabs, oysters, fish, and wildlife. They measured speed of water to determine how boats could safely pass through the slots in the planned berms. Though the project’s goal was not to improve the way ships move through the channel, the team’s scrutiny of vessel traffic was necessary, because “the coast of Louisiana is a working coast, so we don’t want to interfere with commerce,” Meselhe said.

Then, finally, the project received money to move it into construction. In July 2016, it received sixteen million dollars in design and engineering money from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill penalty funds. And in March 2017, Governor John Bel Edwards, in a letter to President Donald Trump, asked the federal government to fast-track federal permitting and reviews of five high-priority coastal-protection projects, including the Ship Channel plan.

The project team is now trying to determine the plan’s finer points, such as how long the berms should be and how many slots need to be opened for boats and fish. “The more you create openings, the less salinity you are mitigating,” Feldbaum said, noting that they will be working with boaters and fish experts to determine “that sweet spot.” With each step, Feldbaum’s team has a closer view of the project, he said. “The airplane is now flying much lower to the ground. We’re continuing to zoom in on what each feature may look like.” But for now, there’s more feedback to gather, more modeling to be done, more permits and reviews to complete.

Hayden said that, while his first concern is keeping the port running, he and other stakeholders in his group also wanted to ensure that the marsh doesn’t deteriorate further—not only for the sake of flood protection, but also because most people here see the wetlands as part of their lives.

“We live here too,” said Hayden, who used to hunt and fish in his younger days. “So I know that it’s a beautiful place to be, an incredibly beautiful place that we need to recreate and restore and nourish.”