Book Excerpt

Clifton Chenier’s Zydeco Road

Clifton Chenier’s path in the zydeco musician’s own words and those of his fellow travelers and bandmates

Published: December 1, 2015

Last Updated: April 29, 2019

Editor’s Note: In this excerpt from his new book, Way Down in Louisiana: Clifton Chenier, Cajun, Zydeco, and Swamp Pop Music, author Todd Mouton retraces Chenier’s path in the zydeco musician’s own words and those of his fellow travelers and bandmates.

At first, he didn’t want to go. “Man, I ain’t goin’ up to California. … They tell me them people bad over there,” Clifton Chenier told African American recordman J.R. Fullbright in 1954. The Los Angeles-based entrepreneur had financed the bandleader’s first recording session at an AM radio station in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and Fullbright urged Chenier to move up to the big time. Years later, Chenier remembered the independent record label head telling him, “You play too much accordion to be up in them lil’ ol’ swampy place like this.” But the future self-proclaimed “King of Zydeco” was not sure he wanted to travel to the West Coast to record.When he did, the floodgates opened. From L-a. to L.-A. and far beyond, the French-speaking Creole accordionist spent the next 33 years blazing a trial from the rural dancehalls of St. Landry Parish to international stages and the White House. Along the way, the man who journeyed from sharecropper to worldwide recognition has been awarded two Grammys, including one for lifetime achievement, and his Bogalusa Boogie album has been honored with inclusion in the Grammy Hall of Fame.“This man took this music, he introduced it in Europe, he introduced this music everywhere,” longtime Chenier collaborator and tenor saxophonist John Hart said. “And anywhere on this globe that you can walk, you call the gentlemen’s name, Clifton Chenier, people know about him. He made it possible that accordion players went abroad. And some of ‘em excelled, very fluent, with this zydeco thing.”

Chenier is now synonymous with the genre he crystallized, but it’s easy to imagine his initial reluctance to cross the country for a better shot at the mainstream. And when he and his bandmates packed themselves into an un-air-conditioned car pulling a humble gear trailer, the musical pioneers were likely unaware that they were embarking on one of the most significant journeys in the history of American roots music.

Today, it’s hard even to think of touring without mobile phones, GPS satellites and e-mail, but the St. Landry Parish native’s ambition couldn’t wait for pagers or fax machines. His music was burning a hole in his soul, and his band followed the Creole route west, through Catholic church halls and any other venue it could find, laying down barn-burning, nonstop four-hour dances.

A Los Angeles performance Fullbright set up quickly led to a contract for the Specialty label, which was already home to several artists with Louisiana roots, including Percy Mayfield and Frankie Lee Sims.

“We went on and recorded the record [“Ay-Te Te Fee,” tracked in April 1955 in Los Angeles and released as a single on Specialty a month later] and I’ve been going ever since,” Chenier told Cajun musician and author Ann Savoy. “New York, Chicago, Florida, but they had me with a fellow named Lowell Fulson [the blues guitarist, singer and songwriter then touring in support of “Reconsider Baby”]. He had some hit records out. Mine was a hit, too, but mostly down here. His was a hit in New York, Chicago … so he was carrying me in New York, but I was carrying him down here.

“He really showed me the highway. I was green, you know. That man even showed me how to stand up on the bandstand. How to present myself to the people. And he’d talk to me. I’d ask him questions, and he’d talk to me and I’d listen. And I’d say, ‘yeah, I’ll learn all that.’ I learned a whole lot by following those fellows.

“I’ve been on the road with pretty near all the artists you can call: Lowell Fulson, Bobby Bland, Junior Parker, Jim McCracklin, Pee Wee Crayton, T-Bone Walker, Five Royals, The Midnighters, ‘Eddie’ James, Bill Doggett, Ray Charles, Little Richard, me and Jimmy Reed and Chuck Berry. I met everyone you could call, mostly.”

Clifton Chenier, the future “King of Zydeco” was billed as “The King of the South” as early as the 1950s. Courtesy of Herman Fuselier.

Press photos from the period feature a smiling, elegantly coiffured Chenier in a coat and tie behind his accordion, and South Louisiana-born saxophonist Lionel Prevost was along for some of that ride. The tenor man was born south of New Iberia, near Franklin, Louisiana, and he grew up in Port Arthur, Texas, where his dad worked at the Texaco refinery. Clifton and his older brother and percussionist Cleveland were also working in the area at the time.

“Clifton Chenier was a neighbor of mine when I was a young kid and I used to watch him all the time sittin’ on the front porch playin’ on the accordion,” Prevost told writer and photographer Paul Harris. “Sometimes I would play the rubbin’ board for him. One day he came through town, he had recorded these new songs, ‘Ay-Te Te Fe’ and a couple of others and he happened to need a saxophone player and I wasn’t doin’ anything at the time so I started workin’ with his group.”

Touring, especially in those days, was a mix of homespun hijinks and grim realities. “We was in Los Angeles, California, playing out of a nightclub they call the 5-4 Ballroom down on Broadway, and the stage was quite high, at least five feet off the floor in front of the dance floor,” Prevost said. “This particular night I had struck a pretty nice groove, man, and we had a thing going because the band would come up and do about 45 minutes to an hour before any one of the artists would come up.

Touring, especially in those days, was a mix of homespun hijinks and grim realities.

“Bill Doggett had just recorded ‘Honky Tonk’ and it was sweeping the country and we were one of the first bands in the country to learn it, and I learned this song note for note, man. This night we had a crowd of people in front of this bandstand that was screamin’ and hollerin’ and, you know, your crowd can really charge you up when they’re into it, man. But I had on a pair of shoes that had holes in the bottom so we’d take some cardboard and stuff [it] in the bottom of these shoes to keep our feet from draggin’ the ground.

“I had a deal I used to do when I played saxophone when I was young and we’d get into it, I’d get on my knees or I’d fall on my back and me and this other saxophone player would kick our heels up in the air, man. This particular young lady that I was tryin’ to impress, when I fell on my back and kicked my heels up in the air, she hollered, ‘Look, he’s got holes in his shoes’ and everybody cracked up because they thought this was part of the show, but they just don’t know, these holes were for real. Musicians traveling on the road, making $17.50 or $22 a night—it doesn’t last very long in a place like Los Angeles or Nevada.”

The accordion player’s groundbreaking band also came face-to-face with the harsh realities of segregation and racism. “I was traveling on the road with Lowell Fulson, Clifton Chenier and Etta James,” Prevost told Harris. “We had a package together, we were doin’ some touring. We were on our way back from Chicago, back down to the South and we had some cooking utensils and things. We would stop on the side of the road, we found it cheaper to eat this way. We’d stop in a store somewhere and buy us a bunch of food, stop with this camping stove and we’d make sandwiches or fried chicken or pork chops or what have you.

“As we got into Mississippi, we spotted a roadside park after we left the grocery store and we pulled in. There was this couple sitting way on the other side of the park, a man and a lady, a white couple. So when we drove through we spoke to them and when I asked the lady, ‘Mind if we share the roadside park with you?’ she said, ‘It’s a public place, go right ahead.’

“About two or three minutes passed, and they got in their car and they left. About five minutes later, here we were cooking hot eggs and hot chicken on the fire and these two carloads of state troopers pulled up and they asked Etta, ‘What are you doin’ ridin’ around with these black guys?’—well they used some other language! She say, ‘Well, I’m black too’—you know Etta James is a very fair-skinned young lady, blonde hair—and he asks us, ‘Are you boys about ready to leave?’ So we mentioned the fact that we’d just gotten there, we’d been drivin’ for a couple of days and we decided to stop and have a little rest and get somethin’ to eat and we’d be on our way after a while. He say, ‘Well, you can eat in the car or you can eat in jail, but you gonna have to get out of this roadside park!’ ”

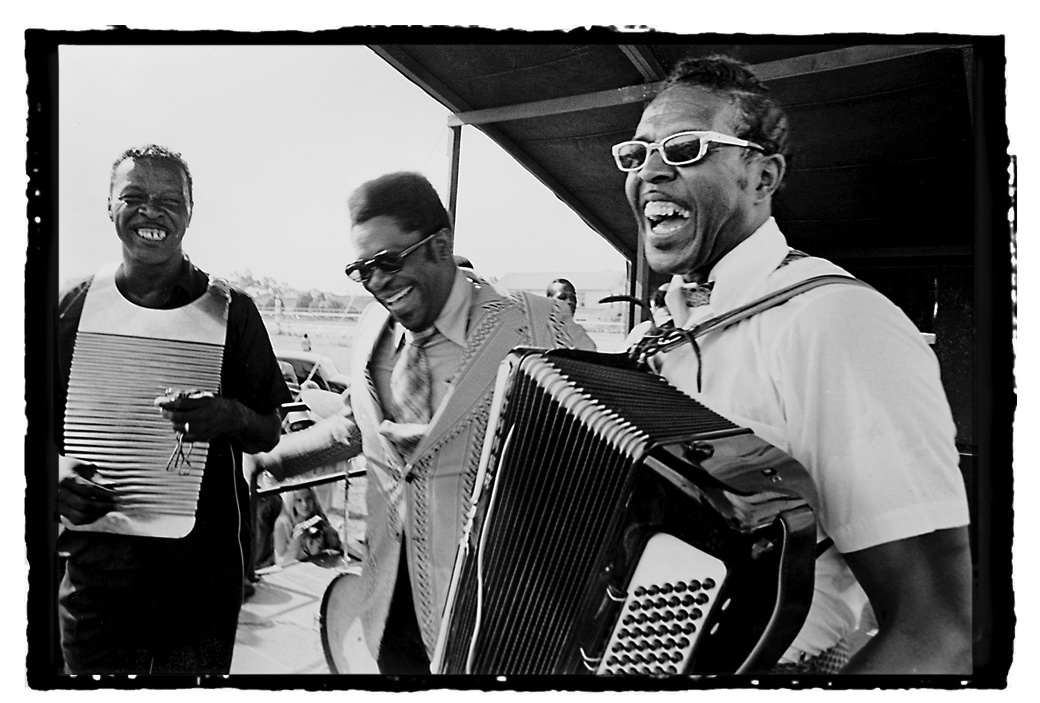

Cleveland Chenier (1921-1991), B.B. King (1925-2015) and Clifton Chenier (1925-1987) on the Blues Stage at the 1972 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, © Michael P. Smith, 2007.0103.4.625

After two more studio dates for Specialty, Chenier recorded for Chicago’s famed Chess Brothers as well as noted Crowley, Louisiana, recordman J. D. Miller. But the bandleader didn’t really hit paydirt again until he hooked up with an eccentric German from Northern California named Chris Strachwitz. The tracks Chenier and his group recorded in the mid-1960s in Houston for Strachwitz’s Arhoolie label are now considered the bedrock of the modern zydeco sound, and they led to an invitation to record in the Bay Area.

“From Bridge City, Texas, all the way going into Vancouver,” “Jumpin’” Joe Morris, Chenier’s longtime bassist, said, remembering his first multi-state tour as part of the ensemble that would become known worldwide as Clifton Chenier & His Red Hot Louisiana Band. The group played hip-shakin’, four-hour dances at a number of Catholic church halls as they threaded up the West Coast playing for audiences populated in part by Louisiana Creoles who’d migrated in search of greater economic and social opportunity.

“We’d play the same clubs on the way coming back. And our last gig on the way back was in Bridge City, Texas.” The club was Sparkle Paradise, just across the Rainbow Bridge over the Neches River from Port Arthur. Run by owner Tiny Richardson, the dancehall was later immortalized in song by Louisiana/Texas pianist and bandleader Marcia Ball. “Oh man, it was a huge club,” Morris explained. “It was really huge. And everybody would turn out. People were like, you know, on the bandstand, we were standing high over and it would look like, you know, ants, there were so many people that was there,” the bassman said.

The accordion player’s groundbreaking band also came face-to-face with the harsh realities of segregation and racism.

Morris’ first studio date with the group resulted in the epochal and desolate Black Snake Blues album.

“After that, we came on back,” Morris explained, describing the tour that followed the band’s 1967 recording session in Berkeley. “So we played one [dance] in Houston at St. Francis of Assisi [Church Hall], from there we played in Bridge City comin’ back. From there, well, Cliff he left. He stop and got his car in Houston and he came in his car, so we took the bus and we came on back with the trailer. Then he start travelin’ some more, then he say, ‘Well boys,’ he say, ‘Chris and I talk,’ he say, ‘We goin’ to Paris.’ I say, ‘Man, come on, well you jivin’.’ He say, ‘No I ain’t. But first we got to go to Switzerland.’ So, ‘OK, that sounds good.’ ”

Guitarist extraordinaire and longtime Red Hot Louisiana Band member Paul “Lil’ Buck” Sinegal also was an integral part of the first modern zydeco band’s trips overseas. “They love us over there,” the innovative zyde-blues guitarist said, recalling a 1977 trip. “Crazy about us. Man, you say that name, Clifton Chenier, boy, awwwwww. I remember we played a whole week at a place they call La Palace in France. Thousands of people every night! We played every night. For a whole week, boy, that man pack that up every night. And the motel, we’d walk out the motel, one, two, three steps, you turn, go right, you’re on the bandstand. And we’d go, we’d play an hour and 45 minutes a night, that’s all. In them times, they was payin’ $15 to go hear him, too.”

Life on those trailblazing tours, however, was often far from glamorous.

“We’d get paid by the night,” Morris remembered. “About 15 or 20 dollars a night. Depends on how much [Chenier] make to the gig, you know. We always knew that he had to keep most because he was bearin’ all the expenses, you know. Matter of fact, we had to pay our own rooms, ’cause we wouldn’t stayin’ in no motel. We’d stay in, he have friends have houses. And we’d pay them so much a week to sleep an’ tuh eat. They’d charge us like $49 or $50 a week. In other words, like, you know, they had washers and dryers if we want to wash and dry our clothes and stuff like that. And sleep and stuff like that. We’d didn’t too much mind that, you know. Sometime we had to sleep on the floor, sometime some would have to sleep in the bed, you know. And some places we stayed we had to sleep up, crawl, you know, get upstairs, and maybe they had one or two beds up in there. And payin’ $50 a week for that. So we said this ain’t gonna’ make it, man. So that’s why Pete [Chenier’s West Coast agent Davis Pitre] said why don’t some of y’all come and stay to my house. Now, that was great, there.”

Clifton Chenier’s customed-decorated vans and trailers carried his band to countless gigs. Courtesy of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, collection of Johnnie Allan and the Center for Louisiana Studies

When they arrived at Pitre’s house, another Louisiana Creole joined the touring outfit. “Now we had a driver over there. His name was Arthur Arceneaux. And he knew, man, all about California. He knew the roads backwards. Originally from Lake Charles but he had been livin’ in California for so many years. When we’d drive in to California, we’d always drive in to Big Pete’s house. And when we’d get there, Cliff would take the keys, he’d throw it to him. [He’d] say, ‘Arthur, it’s your bus. I’ll tell you where to go, what time we gon’ leave,’ he said, ‘Now, it’s up to you to get us there and get us to the next gig where we goin’.’

“When Buckwheat [Zydeco, Red Hot alum Stanley Dural Jr.] had his band, last time Buckwheat went, not too long ago, when he [Arthur Arceneaux] was livin’, he was drivin’ Buckwheat. ‘Cause they didn’t know the roads like he did. He’d tell Cliff, he’d say, ‘Look, we’re not gonna go through this town here. He say ‘because we’d be goin’ the long way.’ He’d say ‘we’ll cut off over here.’ He’d say ‘we’re gonna save 40 or 50 miles,’ you know. And you better believe it, we did. He saved Cliff a lot of money, man.”

In between longer runs, the group played countless gigs on the South Louisiana-East Texas “crawfish circuit.” East of Lafayette in St. Martin Parish, they’d regularly play an early set in Parks, before heading to nearby St. Martinville for another gig the same night. They also were regulars at a Breaux Bridge club called Blind Bébé. “And the same people would pack them places,” Sinegal recalled.

The group played hip-shakin’, four-hour dances at a number of Catholic church halls as they threaded up the West Coast playing for audiences populated in part by Louisiana Creoles who’d migrated in search of greater economic and social opportunity.

Back in Lafayette Parish, the crossroads of major north-south and east-west highways, the group played a number of venues including Austin Mouton’s Club in Milton and Hamilton’s Club, both on the south side of the parish. They also regularly performed farther south in New Iberia, “The Queen City of The Teche,” and in the nearby Bayou Teche community of Loreauville.

North of Lafayette, they gigged in Opelousas and at Richard’s in Lawtell. “In Leonville [southeast of Opelousas], they had a club called Thomas and Thomas, it was two brothers,” Sinegal remembered. “Well, that’s where Cliff’s from, man. … We broke the floor one night. The floor just went—yeah, they was on the dance[floor], had water all under, people’s shoes all muddy—they had water all under that club, man. Then we’d go to Arnaudville, Cecilia, The Gypsy Club, we’d play there. And another one in Breaux Bridge, on this side of the bridge, Club DeLisa. You had the Rice Building in Crowley, nothin’ in Rayne, bunch of places in Lake Charles, the Catholic hall in Lake Charles once a month. Then Beaumont, Port Arthur, all over Houston … every Catholic hall, I believe we played about 15 Catholic halls [in Houston].”

On their way home, Sinegal said, the band would play Sunday nights at Sparkle Paradise before its regular Monday night dance at The Blue Angel in Lafayette’s African American McComb Addition neighborhood.

And there were tell-tale signs when an extended journey was in the works.

“I’ll never forget,” the guitarist said. “Cliff would go have the wheels on his little trailer packed with that grease, you know. When you’d see it, that mean we headin’ for the road. All through California, Canada. We played all the way goin’, you know, like Seattle, Portland, Oregon, all the way to Vancouver, Victoria. Then on our way back, we’d play them same places comin’ out. Then we’d always stop in Austin and play the whole week. Six [nights]. We’d travel the Sunday to play to The Blue Angel the Monday. He’d had his gigs fixed up just right. ’Cause, see, every Monday he would play at The Blue Angel was the first of the month when the old people got their check.”

Regarding the rewards of the often-grueling roadwork, Sinegal said simply, “We weren’t doing it for the money, no. We were doing it ’cause it was fun.”

Excerpted with permission from Way Down in Louisiana: Clifton Chenier, Cajun, Zydeco, and Swamp Pop Music, by Todd Mouton, published by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, copyright 2015. For more information on the book and related film projects, visit waydowninlouisiana.com.

Excerpted with permission from Way Down in Louisiana: Clifton Chenier, Cajun, Zydeco, and Swamp Pop Music, by Todd Mouton, published by the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, copyright 2015. For more information on the book and related film projects, visit waydowninlouisiana.com.