Latest

COVID Geography: Notes from New Orleans

This special quarantine issue of Geographer’s Space is produced in partnership with LSU Press

Published: March 19, 2020

Last Updated: September 5, 2022

Photo by Tshombe Tshanti

The French Market in New Orleans’s historic French Quarter sits empty as the city hunkers down during the COVID-19 crisis.

March 19, 2020

Writing during the first major week of the national coronavirus reaction, as so many aspects of life grind to a halt, I find my senses nearly overloaded with a Brave New World’s-worth of geographical observations.Here in a city renowned for social propinquity, New Orleanians, like folks everywhere, are learning the awkward dynamics of social distancing. Crowded restaurants, packed bars, second-line parades, festivals, the Mardi Gras revelry of barely a month ago—not to mention the hugging and backslapping of this gesticulating society—all now have us recoiling and uncharacteristically standoffish. It took a few days of browbeating from authorities, but over the course of four days, from March 14 through March 17, street gatherings dispersed, Bourbon Street emptied, bars shuttered, and restaurants scaled down services (behold: Galatoire’s to go). We’ve become hyperaware of human geography at its most literal level—body space—and, darkly, we’re coming to see that approaching stranger more as a threat than a friend not yet met.

Scale this up to the global level, and we’re seeing profound affects in economic geography—lessons in supply chains, manufacturing, trade, inventory, distribution, and just how mobile we’ve become. In some regards, the script has flipped. Places more wired into the global economy, bustling with interactivity—the very places that have benefitted from globalization—are now bearing the brunt of its consequences. In contrast, small towns and postindustrial cities, areas left behind by globalization, are seeing less of the viral spread and the economic slowdown.

Antoine’s, the oldest family-run restaurant in the United States, shuttered after Governor John Bel Edwards mandated all restaurants cease eat-in operations on March 16, 2020. Photo by Tshombe Tshanti.

Relatedly, maps indicate that COVID-19 is far more a problem of the wealthier Global North –that is, the First World—than of the developing Global South (though this may soon change). Within the United States, it’s no surprise that big coastal metropolises were affected first and worst, while poor, rural West Virginia, with its socially distancing mountains and lack of major travel hubs, was the last state to get a positive case. Within Louisiana, most cases are urban, and not in just any cities. New Orleans, with its robust visitation economy and famously aggregating social milieu, has vastly more cases than its similarly sized and fairly close neighbor, Baton Rouge, known for neither tourism nor second-lines.

Public-health researchers will long be studying exactly where, when, and how this virus spread, a topic in geography known as spatial diffusion. Three major movements are at play: contagion diffusion, in which bodies come in close physical contact; relocation diffusion, in which persons move from place to place, potentially spreading the virus contagiously as they relocate; and hierarchical diffusion, in which the virus initially spreads among primary cities because they are more interconnected, before working its way down into secondary and tertiary cities and rural areas.

Readers of 64Parishes, if they’re like me, probably exert much mental energy trying to “channel” the past, empathizing with its people and imaging what their everyday lives were like. Well, here’s a chance to partake of one major aspect of those lived experiences, namely, what it was like to regularly endure epidemics, to have utter uncertainty thrust upon you, and to have your life turned upside down within a few days.

Among folks in New Orleans, coronavirus conversations often invoke Katrina memories. Restauranteurs recall their down-staffing and limited menus during the evacuation and diaspora of 2005–2006. Parents remember the improvised child-rearing, and workplaces frantically grappling with the latest communications technologies, be it texting and Wi-Fi in 2005, or Zoom and Teams in 2020. “Comparisons are odious,” my mother used to say, so I’ll refrain from pointlessly comparing the two very different traumas. But one observation, I believe, is worth mentioning: those of us who lived through Katrina remember what a lonely experience it was. Greater New Orleans was isolated from the world for days and weeks, and in the aftermath, we found ourselves set so far back, while everyone else progressed forward. In that regard, the COVID-19 pandemic is the anti-Katrina: we’re all going through this; it is among the most universal major anomalies experienced by humanity in a century. So this time, New Orleanians don’t have to defend their city, or argue for their right to return, or explain their culture to compassion-fatigued Americans, because everyone’s going through nearly identical experiences.

The shared nature of this event may be somewhat comforting, but it also has a corollary. We should expect no outpouring of sympathy, interest, volunteerism, and federal aid, the likes of which flowed into Louisiana and New Orleans abundantly after the floodwaters drained. We’re all in this together now, and later, we’ll all be waiting in the same assistance line. For once, we’re anything but unique.

In the meantime, we have an opportunity to make meaning out of this disquieting experience. Readers of 64 Parishes, if they’re like me, probably exert much mental energy trying to “channel” the past, empathizing with its people and imaging what their everyday lives were like. Well, here’s a chance to partake of one major aspect of those lived experiences, namely, what it was like to regularly endure epidemics, to have utter uncertainty thrust upon you, and to have your life turned upside down within a few days.

Even if most of us never get COVID-19, we’re all feeling its enormous global economic impact, and therein lies another opportunity for historical empathy. Fear of yellow fever triggered a near-annual avoidance of New Orleans during its late-summer “sickly season,” with dire economic consequences. Dread of the plague scared off vessels calling at the port, costing money and jobs. It drove away visiting businessmen as well as wealthy residents, who, in the social distancing of the day, took refuge inland or at coastal getaways like Grand Isle, Pass Christian, or Biloxi. With them went their capital, and their departure stifled cash flow and commerce—which only intensified the pressure to flee.

“In summer it becomes intensely hot, and the resident is cruelly annoyed by the musquitoes [sic],” reported traveler Hugh Murray in 1828. Unaware of the relationship between the invasive Aedes aegypti mosquito and the “terrible malady,” Murray wrote that yellow fever “makes it first appearance in the early days of August, and continues till October. During that era New Orleans appears like a deserted city; all who possibly can, fly to the north or the upper country, most of the shops are shut, and the silence of the streets is only interrupted by the sound of the hearse passing through them.”

It’s chilling to consider how much of that last sentence could also describe today.

The historical parallels continue, even if the magnitude is incomparable. Like COVID-19, which disproportionally endangers elders and the infirm, yellow fever was also not egalitarian. Newcomers were thought to be particularly vulnerable, justifying the nickname “the strangers’ disease.” Perhaps this came from lack of prior exposure; more likely it derived from the living conditions of transients—in crowded boarding houses, and of immigrants—in muddy banlieues and purlieus such as the Irish Channel or the back-of-town. Many believed those of African ancestry, as well as those born in the city (Creoles, thought to be “acclimated” to the virus through childhood exposure) were more resistant to yellow fever, although this was likely more perception than reality. What was all too true was that the poor suffered more than the rich, for reasons of differing residential environs and lack of financial wherewithal to depart. New Orleans during plague years thus constituted a markedly quieter, riskier, poorer, less cosmopolitan, more Creole, more black, more gender-balanced (because most businessmen and sailors avoiding the city were male), more Catholic (because those who departed were more likely to be Anglo, Protestant, and English-speaking), and more Francophone urban environment than wintertime New Orleans.

“I am now at the head-quarters of Death!” bemoaned visitor Henry Tudor in 1831, “and were it the month of August or September[,] I should scarcely expect to be alive this day [next] week.” Only one year later, the city’s worst-ever cholera epidemic claimed 4,340 lives and scared away another 11,000, again with grave economic effects. The year 1853 proved to be the city’s worst-ever yellow fever scourge, claiming around 12,000 lives, roughly one in ten. In all, over 100,000 Louisianians died from “yellow jack” between 1796 and 1905, including over 400 in the nation’s last-ever epidemic, in the predominantly Sicilian immigrant community of the lower French Quarter.

If all this seems unimaginable, I dare say it’s a little less unimaginable than it was in January. And it’s about all the historical “channeling” I need.

Looking to both the past and the future, there is reason for hope. In 1914, for example, the dreaded Bubonic Plague paid a visit to New Orleans. It could have been calamitous, but instead, New Orleans, with its stellar medical community borne of the effort to defeat yellow fever, deployed a rigorous science-based rodent-control and rat-proofing campaign that became a template for other cities to follow. Within a year, it was over, and very few people died.

Looking forward, there’s plenty of reason for hope. Unlike after Katrina, we will suffer no lingering structural effects or civic stigma. Once we get the all clear, I sense the visitation economy in the state’s hardest-hit city, New Orleans, will come roaring back, as people enduring months of social distancing will be eager to indulge in its exact opposite: social propinquity, rescheduled festivals galore, crowded restaurants, packed bars, rollicking second-lines—and abundant hugging.

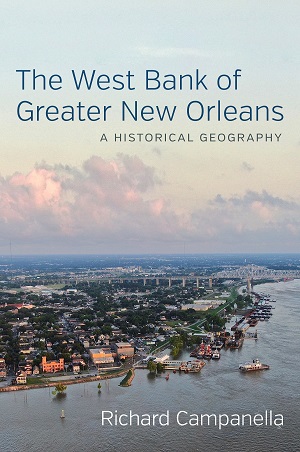

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, Bourbon Street: A History, and the forthcoming The West Bank of Greater New Orleans. The historical material in this essay are drawn from his 2010 book, Lincoln in New Orleans. Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected]; or @nolacampanella on Twitter.

Available May 2020

Hardcover | 448 pages

$34.95

Geographer Richard Campanella’s The West Bank of Greater New Orleans: A Historical Geography is available now for preorder through LSU Press.

Liked this article? Subscribe to 64 Parishes today to support our efforts to bring you the best stories covering Louisiana history, culture, foodways, art, and more. Thank you for your support, and thank you for reading.