Spring 2014

The Cracker Jack: A Hoodoo Drugstore in the “Cradle of Jazz”

The Cracker Jack was apparently operating as a hoodoo drugstore by the 1920s, supplying customers all over the eastern United States

Published: October 2, 2017

Last Updated: December 19, 2018

Hoodoo consumers were assured that “John the Conquerer,” an extract of jalap root, would bring them luck. Courtesy Carolyn Morrow Long.

This iteration of the Cracker Jack, barely hanging on in a modernizing city, was the final home of a business that had started on South Rampart Street long before New Orleans’ gleaming City Hall replaced the neighborhood where Louis Armstrong was raised. From the late 1800s through the 1950s, the South Rampart Street neighborhood was the preeminent African American commercial and entertainment district. Preservationists and historians have become increasingly outraged about the destruction of this area. Particular attention has focused on the odd-numbered side of the 400 block of South Rampart, where only four buildings remain standing. During the formative years of New Orleans jazz, these housed the Little Gem Saloon, the Karnofsky family store, the Iroquois Theater, and the Eagle Saloon. The Little Gem has recently been restored, and the severely dilapidated Karnofsky Store, the Iroquois Theater, and the Eagle Saloon have been designated as local landmarks to protect them from demolition. But the 1972 razing of the Cracker Jack, New Orleans’ most famous and longest-running “hoodoo drugstore,” engendered absolutely no outcry at the time. Today even locals have forgotten the Cracker Jack, and this once-notable institution is known only to scholars of African American spirituality and magic.

Voudou and Hoodoo

New Orleans is often associated in the popular imagination with “voodoo,” a term that evokes images of malevolent spells and pins stuck in dolls. In reality, Voudou, as it is properly called, is a legitimate religion that developed in 18th- and 19th-century New Orleans, where Catholicism merged with African traditions. Elsewhere in the Anglo-Protestant South, African-descended people practiced a system of healing and magic known as conjure, rootwork, or hoodoo. Before the abolition of slavery, hoodoo was most often employed for health and well-being and for protection against an abusive master. Later on, hoodoo was directed toward ensuring beneficial interactions with lovers, family, friends, customers, and employers, guarding against those who intended harm, confounding enemies, and controlling external forces like luck. These ends were accomplished through rituals and the use of powders, baths, oils, and magical power objects—called gris-gris in New Orleans—made from common household substances, plants, minerals, and animal parts. By the turn of the 20th century, the Voudou religion had been forced underground by lawmakers, public opinion, and the church, but believers continued to practice a distinctly New Orleans style of hoodoo.

Rural practitioners gathered fresh materials in the wild. In the city, people were more likely to buy herbs and other ingredients at the pharmacy, which stocked dried roots, leaves, barks, flowers, berries, seeds, and resins—referred to as “botanicals”—as well as the drugs, oils, essences, flavorings, and other raw materials from which healing preparations were formulated. We know from George Washington Cable’s 1880 novel, The Grandissimes, that 19th-century New Orleans drugstores were considered a source for supernatural paraphernalia. Cable depicts a woman of French descent buying basil for good luck at an apothecary shop, and a free man of color asking for a wanga, an especially powerful type of gris-gris. When the proprietor denies any knowledge of such things, the customer expresses surprise: “Vous êtes astrologue—magicien?” (Are you not an astrologer—a magician?)

By the early 20th century, so-called “hoodoo drugstores” could be found in many African American neighborhoods, not only in New Orleans but in most southern cities, and with the exodus of blacks to the North during the Great Migration, these establishments also appeared in northern cities. The hoodoo drugstore usually began as an ordinary pharmacy operated by a white, professionally trained pharmacist. Those who served a predominantly black clientele simply responded to the requests of their patrons and gradually found themselves formulating “magical” potions. The desired result determined the color and smell. Pink was for love, blue for protection, white for peace, red or purple for victory, and green or gold for wealth; these positive charms had a pleasant scent. Those meant to cause strife and bad luck were colored brown or black, and had a disagreeable odor. “Hot” ingredients such as ginger and pepper were added to make the mixture seem more powerful. Lodestone, a magnetic ore, was popular because its ability to attract iron filings symbolized luck-drawing and attraction. Eventually the hoodoo drugstores sold not only natural herbs, minerals, and animal parts but also incense, candles, oils, perfumes, powders, and soaps that were alleged to have occult properties. They also sold books of dream interpretation and magical formulae.

A small notebook, dated 1910, is now on display at the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum. The pages are filled with handwritten recipes for toothache drops, cough syrup, dandruff cure, and tapeworm mixture. But the first two pages contain formulae for hoodoo concoctions. “Van-Van,” a popular good luck charm, called for oil of cinnamon, oil of lemon grass, oil of rosemary, and denatured alcohol. “Hoodoo Mixture” was made from gum olibanum (frankincense), grains of paradise, iron filings, lodestone, and cayenne pepper. Both sold for ten cents an ounce. “Wa Wa Water” was tincture of cochineal (a red dye), iron filings, oil of cassia, and water; it was to be “sprinkled on the floor and around the yard” to repel enemies, and sold for twenty-five cents an ounce. The Pharmacy Museum also exhibits brown glass screw-top jars bearing hand-lettered labels such as Love, Controlling, Flying Devil, Get Away, Come to Me, Success, Goofer Dust, and Family Powder. The jars are numbered, presumably for easier ordering.

Back o’ Town Business

The Cracker Jack Drug Store, located at 435 South Rampart Street, was owned by George Andre Thomas. Thomas was born in New Orleans to Belgian parents in 1874. His family home was an attractive frame house on Chestnut Street in a middle-class white neighborhood in the Lower Garden District. Thomas began, like other white pharmacists, by operating an ordinary drugstore and eventually became a hoodoo entrepreneur. He first appeared in the city directory for 1896, where he was listed as a clerk at the drugstore of Pierre Caillier at 1132 Poydras Street, just off South Rampart. George Thomas lived with the Caillier family in rooms above the store. By 1897, he had taken over Caillier’s business and renamed it George A. Thomas Drugs. He received his medical degree from Tulane University in 1907 and was listed in the city directory as both a druggist and a physician. According to the American Medical Directory for 1912-14, he specialized in urology.

A few years after establishing George A. Thomas Drugs on Poydras Street, Thomas began acquiring property in the square designated 297, bounded by the 400 blocks of South Rampart and Basin streets and the 1100 blocks of Perdido and Poydras streets. During the next couple of decades Square 297, and the surrounding “Back o’ Town” area would play a significant role in the development of jazz. The Golden Dragon, Parisian Roof Garden, Cinderella Ballroom, the Odd Fellows Hall, Pythian Temple, and the Union Sons of Honor Hall (nicknamed the “Funky Butt”) featured the most important jazz performers of the day, such as Buddy Bolden, Louis Armstrong, A.J. Piron, Papa Celestin, and John Robichaux. The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club Mardi Gras parade started on South Rampart, and it was there that the Baby Dolls masking tradition began. Young Louis Armstrong shot off a handgun in front of the Eagle Saloon at the corner of South Rampart and Perdido on New Year’s Eve 1913 and landed in the Colored Waifs’ Home.

Even after Storyville, New Orleans’ officially created red-light district, was closed down in 1917, another unofficial “vice district,” sometimes called Black Storyville, continued to flourish near the South Rampart Street corridor. With prostitution came sexually transmitted diseases, and in 1929 the Cracker Jack published a little booklet titled The Complete Root Doctor, offering cures and advice for various ailments, especially syphilis and gonorrhea. The Cracker Jack sold “Old 76—the standard remedy for unnatural discharges,” “White C Powder—for men only,” as well as “Naturine Tablets” and “Neuro-Fort” for impotence caused by venereal disease. These were presumably herbal remedies formulated by Dr. Thomas, a specialist in urology.

George A. Thomas, as a man of Belgian Catholic descent, was something of an anomaly among Back o’ Town’s population of laboring-class Protestant African Americans and Eastern European Jewish merchants. He nevertheless seems to have been attracted to the neighborhood and chose it as his home and place of business. In 1906 Thomas paid second-hand dealer Abraham Schulmann $11,500 for a two-story brick store at 435 South Rampart. The following year Thomas moved his pharmacy to this building and lived in the upstairs apartment. At first the business was listed in the city directories as George A. Thomas Drugs, but by at least 1914 it was known as the Cracker Jack, a term signifying something sharp, snappy, or first-rate.

In 1909 Thomas bought two more buildings in Square 297. He paid Selig Pailet, another second-hand dealer, for a store at 413-415 South Rampart. Pailet continued to operate his store there until 1912, when it became the Iroquois Theater, a vaudeville house that featured African American touring acts, local performers, and motion pictures for black audiences. Thomas was never involved in the management of the Iroquois; he leased the space to Paul L. Ford. The theater was in business until 1927. Thomas also bought 427 South Rampart, adjacent to his drugstore, from pawnbroker Jacob Itzkovitch. Within a few years he had rented the building to the Karnofsky family, beloved in jazz history as the benefactors and surrogate parents of young Louis Armstrong, who lived at the time at the corner of Liberty and Perdido streets.

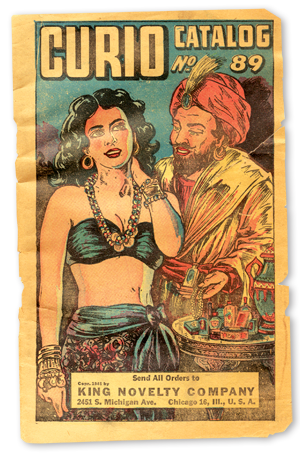

“spiritual products” that churned out soaps, talcs, and elixirs with exotic labels suggesting conjuring powers. Courtesy of Carolyn Morrow Long.

Louis Karnofsky and his wife Rebecca “Tillie” Kaufmann were Russian Jewish immigrants who settled in New Orleans around 1894. By 1914 the Karnofskys had established their home and business in Thomas’ building. In 1919 Tillie was operating a second-hand store, and throughout the 1920s one of the Karnofsky sons, Alex, had a tailoring shop there. The entrance to 427 South Rampart still retains a blue-and-white tile marker, “The Model Tailors,” set into the sidewalk. Another son, Morris, founded Morris Music House, which sold records, musical instruments, radios, phonographs, offered music lessons, and was important as a gathering place for jazz performers. Although it is widely believed that Morris Music was located in the Karnofsky store building, it was actually at 168 South Rampart between Common and Canal.

During these early years, Thomas and two other shareholders formed a corporation called Diana Realty Company Limited, and in 1925 he transferred all of his property in Square 297 to Diana Realty for $35,000 cash. Thomas continued to operate the Cracker Jack at 435 South Rampart and to act as landlord for the other buildings.

Dr. Thomas’ Checkered Past

At around the time that George Thomas opened his drugstore, New Orleans authorities launched a crackdown on cocaine trafficking. “The sale of the drug has become alarming,” declared police chief James Reynolds to a local reporter. “It has taken the place of whiskey … among the negroes and the lower class of whites.” Investigators found that many dealers were illegally obtaining cocaine from local pharmacies. The Cracker Jack attracted police notice in 1910 through the arrest of Virginia Telfrey, a “negress” who lived nearby. Telfrey had dispatched Dave Witmeyer, a white man, to buy cocaine from Thomas’ establishment. She testified that after obtaining a large amount of the drug, she “put it up in small packages and sold it to such as applied to her.”

Charles Lindsey, a clerk at the drugstore, confessed that over a period of several months he had frequently filled prescriptions for Witmeyer, written by Dr. Thomas, averaging two ounces of cocaine. Thomas and Lindsey were arrested, fined $25 each, and sentenced to thirty days in jail, but both managed to wriggle out of the charges. Thomas put the blame on Lindsey and denied having actually sold the cocaine, and Lindsey argued that he was merely an employee at Thomas’ drugstore and was therefore not responsible for his actions.

George Thomas had a complicated personal history. Before marrying the spouse with whom he spent the rest of his life, he had already been married and divorced twice, producing a child from each marriage. His second wife testified in court that “on numerous occasions [Thomas] has publicly called her vile names which, out of respect for this honorable court, will not be inserted in this petition,” and that “regardless of their marriage vows, her husband has lived in adultery with another woman.” In 1912 Thomas was married for the third time to Alice Armande Vibart. Born in 1885 in Bordeaux, France, Vibart had come to the United States in 1905. She already had a young son, Lucien, born in 1907. George and Alice had two more sons together: George, born in 1913, and Andre, born in 1915. The Thomases eventually moved the family from their apartment above the Cracker Jack in gritty, ethnically diverse Back o’ Town to 5620 Hawthorne Place, a bucolic setting near Lake Pontchartrain in what is now the affluent Lakeview subdivision. Their widely scattered neighbors were all white, and most were American-born.

Investigation and Mail Fraud

It is unclear exactly when Dr. Thomas’ establishment made the shift from an ordinary pharmacy to the city’s most famous outlet for hoodoo supplies. The Cracker Jack was apparently operating as a hoodoo drugstore by the 1920s, selling not only to the local trade but also supplying customers all over the eastern United States through its mail-order business.

The U.S. Post Office began to prosecute mail fraud in 1909. Thomas may have managed to avoid the notice of postal inspectors for a number of years, but on May 14, 1927, New Orleans newspapers published front-page articles about the federal mail-fraud investigation of a South Rampart Street physician for “the distribution of love philters, charms, and voodoo magic” in a “widespread traffic in fake potions extending from New Jersey to Texas.” Inspectors were said to “have unquestioned evidence of mail fraud, through there is some doubt as to placing responsibility for the scheme.”

The Morning Tribune article reported that “a voodoo practice with headquarters on South Rampart Street … was exposed … on Friday. The inspectors found the organization manipulated by an aged white physician. His practice … has been entirely confined to negroes whose superstitious nature has enabled him to found a drugstore dealing in such articles as ‘goofer dust’ [graveyard dirt], ‘eagle eyes,’ and other charms for good and evil. … The method used by the voodoo practitioner was to mail out a catalogue of charms ‘purchasable at his drugstore only.’ The list, made up of 250 articles, included black cat bones, blood of hawk, damnation box, Adam and Eve roots, and pictures of the saints.”

According to the newspapers, the drugstore also sold a booklet called The Life and Works of Marie Laveau. This small publication bears no relation to the famous 19th-century Voudou priestess. It contains a series of petitions, each related to a specific problem, followed by instructions for a ritual to alleviate the difficulty using magical supplies available at the drugstore. Written in archaic, pseudo-Biblical language, the petitions had titles such as “The Lady in Trouble with Her Landlord,” and “The Gentleman Whose Love Is Spurned.” The booklet also contained horoscopes, instructions for praying the Novena, a section on the significance of candles, and a short essay on Spiritism—a doctrine founded by the French occultist Allan Kardec. Might the French-born Alice Vibart Thomas have been the creator of The Life and Works of Marie Laveau?

The New Orleans newspapers made no further mention of the mail-fraud case against the “aged white physician,” and his identity was never revealed. No record of the investigation was found in the Postal Service Inspector’s case files at the National Archives or in the records of the United States District Court New Orleans Division. The city directory for 1927 shows five other drugstores on South Rampart, none of those proprietors was also a physician, which strongly suggests that the accused was Dr. George Thomas.

A year later, in 1928, an article in the Sunday magazine section of the Item-Tribune was headlined “Voodooism Still Thrives in New Orleans.” The writer, Marguerite Young, described the Cracker Jack’s South Rampart and Poydras Street neighborhood: “Here you will find ample evidence of spirit worship and voodoo … [with] love-potions and spirit-charms displayed … in a drugstore window.” Young followed “a dark skinned young woman” into the drugstore and eavesdropped as she complained to the clerk that her husband had “gone down the street to see another woman near every night. … I wants to get him back. … I wants some Stay Home Powder and some War Powder. Gimme 25¢ worth of each, please.” The clerk was joined by the owner of the drugstore, probably Thomas, “whose hair is as white as his face.” He “handed the woman a large pink candle” and instructed her to burn it and “say the name of the other woman.” He told her to sprinkle Stay Home Powder on her own body and War Powder on her husband’s body. After the customer left, the journalist questioned the druggist and his assistant about the business and was told, “It’s simple. You just give them what they ask for.” She ascertained that Blue Luck Powder was laundry blueing, Good Business Oil was machine oil, and Dove’s Blood was red ink.

African American writer Zora Neale Hurston conducted anthropological research on New Orleans hoodoo in 1928 and 1929. In 1931 her findings were published in the Journal of American Folklore as “Hoodoo in America,” and a shorter version was included in her 1935 book Mules and Men. Hurston wrote of buying ingredients such as those sold at the Cracker Jack for the creation of gris-gris. In a letter to Langston Hughes, she thanked him for directing her to “the drugstore on Rampart.” Her published works include rituals called the “Marie Laveau routines,” which she claimed to have learned from the nephew of the renowned Voudou priestess. While shopping at the Cracker Jack, she had obviously discovered The Life and Works of Marie Laveau. Most of her “Laveau routines” are nearly identical to those found in the drugstore’s booklet—even some misspelled words are reproduced.

Changes in the Family Business

At some undetermined time, George Thomas began to suffer from mental illness. In September 1934 he was admitted to the East Louisiana State Hospital in Jackson, the same institution to which the great jazz cornetist Buddy Bolden was committed in 1907. Alice Vibart Thomas became president of Diana Realty Company while her husband was confined to the State Hospital, and in 1936 Diana Realty sold the Thomases’ buildings on South Rampart to Louis August Meraux for $18,000. Meraux was a medical doctor, sheriff, tax collector, and public health officer of St. Bernard Parish, and a cohort of the notorious political boss Leander Perez. When Dr. Meraux died in 1938, his estate passed to his only son, Joseph Meraux. The canny Merauxs undoubtedly assumed that the Central Business District would advance across South Rampart and that all property in the way of this “progress” would greatly increase in value.

In 1940, Thomas, age 66, died at the state hospital, and his body was returned to New Orleans for interment in St. Patrick Cemetery No. 2. On the Thomas family tomb is a marble vase inscribed “Dr. G.A. Thomas—Daddy.” Alice was 55 years old when her husband passed away; her three sons, Lucien, George, and Andre, were young adults.

Under Louisiana civil law, a detailed inventory of a deceased person’s estate was taken when his or her succession was opened. A twenty-page document listed every item from the stock of the Cracker Jack Drug Store. At that time pharmacists most often formulated tablets, capsules, syrups, salves, and teas from their own supply of ingredients. Dr. Thomas had chemical compounds, drugs, flavorings, and every imaginable dried root and herb. They all had medicinal properties, but some were also used for magical purposes. For example, jalap root, a strong purgative imported from Mexico, was sold as the famous luck-bringer High John the Conqueror, and viburnum, an anti-spasmodic herb, was offered as Devil’s Shoe Strings.

In addition, the Cracker Jack carried other medicinal herbs that are frequently cited as hoodoo ingredients: cayenne pepper, wahoo bark, cinnamon, orris root, cloves, paradise seeds, and asafoetida. The only items that definitely indicated this was no ordinary drugstore were the lodestones and iron filings, horseshoes, incense burners, eight dozen colored candles, seven dozen Sacred Heart of Jesus badges, 4,000 saints’ pictures, and stacks of books on hypnotism, palmistry, and dreams as well as The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, a popular occult classic. If the Cracker Jack was still selling The Life and Works of Marie Laveau, it was not included in the inventory.

Alice Vibart Thomas took charge of the Cracker Jack while her husband was hospitalized, and she assumed ownership after his death. Even before Dr. Thomas’ illness, Lucien Thomas had been assisting his parents while attending Tulane University’s School of Pharmacy. He became a clerk at the drugstore in 1927 and continued as manager until it closed in 1974. During much of this time, Lucien, with his wife and children, resided in the Thomas family home on Hawthorne Place.

In 1942 Alice Vibart Thomas married her old friend and fellow South Rampart Street merchant Morris Karnofsky, who had shortened his surname to Karno. She had known him since the Karnofskys became the Thomases’ tenants and neighbors in 1914. Morris was involved in his own enterprise, Morris Music House, and seems to have had nothing to do with the Cracker Jack. Alice and her second husband lived in Alice’s Hawthorne Place home, but their union was short-lived; Karno died in 1944. Alice Thomas Karno continued to run the Cracker Jack with the help of her son Lucien, and there were undoubtedly African American employees as well.

An article by Edward Clayton, “The Truth about Voodoo,” appeared in the April 1951 issue of Ebony. Clayton noted the hoodoo drugstores on South Rampart Street: “These druggists fill voodoo prescriptions with the same dispatch and attention they would give to a regular medical draft, although most admit they don’t know if ‘the stuff’ works or not.” He described the Cracker Jack as “a rather forlorn and dismal-looking place that has done a lucrative business dispensing such wares for more than two generations and is still said to be one of the most popular sources of voodoo paraphernalia in New Orleans.”

In 1958 the Cracker Jack was no longer designated as a drugstore in the city directory, but was called Cracker Jack Store—Notions. In 1962 the listing changed again to Cracker Jack Store—Religious Items. By this time the Cracker Jack might have been carrying at least some commercially produced spiritual supplies. The Miami-based Sonny Boy Products, in fact, issued a catalog called The Guide to Success and Power that seems to be based on the Cracker Jack’s Life and Works of Marie Laveau.

Veteran musicians had their memories of the Cracker Jack. The place was immortalized by bluesman Champion Jack Dupree, who sang, “Think I’ll stroll on down to New Orleans, / Go by that Cracker Jack Drug Store, / Get myself some of that goofer dust.” Trumpeter Ernest “Punch” Miller, interviewed by Richard B. Allen of the Tulane University Hogan Jazz Archive, recalled a woman who had a “moonshine joint” and three “sporting houses” in Mobile. She “sent to the Cracker Jack Drug Store here [in New Orleans] for whatever she needed.” Miller “took her note to the man, man sent whatever it is to her—everybody else in Mobile gets arrested, [the police] never touch her. … She never gets in trouble, makes plenty of money. She keeps buying that stuff.” Jazz musician and author Danny Barker also mentioned the Cracker Jack as a source for “everything used by the voodoo doctors, from snake hearts to frog titties.”

Several scholars whose interest was primarily in the former jazz venues on the block attempted to observe the commerce at the Cracker Jack. Richard Allen of the Hogan Jazz Archive noted that he “went in once to buy some stuff for a cold, and they couldn’t understand anybody coming in to buy legitimate medicine. … It’s not ‘open’ to outsiders.” Historian Jack Stewart recalls being ignored by the clerk when he entered the store.

Death of a Drugstore

Bob Newman, a high-school friend of Lucien Thomas’ son in the late 1950s, remembers the Cracker Jack as an unremarkable place that sold drugstore items and other necessities, with the hoodoo merchandise toward the back behind a divider. He often visited the Thomas family home on Hawthorne Place and described Lucien Jr.’s father as one who liked to kid around with the teenaged boys. His friend’s grandmother, Alice Thomas Karno, was a large, amiable lady who spoke with a heavy French accent. She “didn’t get around very well,” and Newman never knew her to work regular hours at the Cracker Jack.

Despite her disability, Alice Karno was still at least somewhat involved in the operation of the business. In August 1969, as 83-year-old Mrs. Karno was closing up the shop, she was attacked and robbed by an unidentified man who subsequently escaped. She was listed in serious condition at Charity Hospital. The neighborhood was becoming dangerous, and this, coupled with declining health and the concerns of her family, might have induced her to retire completely.

The South Rampart Street commercial strip and surrounding residential neighborhood began to disappear in the mid-1950s, during the tenure of Mayor DeLesseps S. Morrison. In November 1955 the Times-Picayune announced that “in place of a slum,” New Orleans would gain a new civic center, including an 11-story city hall, the adjacent civil district court, a park, a state office building, and a new main public library. In 1971, construction began on the Louisiana Superdome, which opened in 1975. Office towers in excess of 50 stories sprang up in the Central Business District. The Cracker Jack and other low-rise buildings were doomed.

In March 1972 the New Orleans City Council, acting on an inspection by the Department of Safety and Permits, authorized the demolition of 441, 439, and 435 South Rampart. These buildings, according to the report, had “become dilapidated and in a state of disrepair and [had] been declared a public nuisance.” Since the owners had not voluntarily razed the buildings, the City Purchasing Agent was authorized to secure bids for the demolition and removal of debris at the owner’s expense. Numbers 441 and 439, as well as many other buildings on South Rampart, had been vacant for years, but the Cracker Jack was still a thriving business until the time of the demolition. Lucien Thomas placed notices in the Times-Picayune advising customers that “the Cracker Jack Store had to move” and giving the store’s new phone number and address, a few blocks away at 138 South Prieur Street.

The Cracker Jack closed for good in 1974, demolished for parking lots and garages, and the corner of South Prieur and Cleveland has since been subsumed into the new hospital complex currently under construction along Tulane Avenue. Alice Vibart Thomas Karno died the following year at age 87. According to her will, she left the stock, furniture, and fixtures of the Cracker Jack to her grandson, Lucien Thomas Jr. Unlike the marvelously detailed inventory attached to George Thomas’ 1940 succession, Alice Karno’s estate settlement offers no further information about the goods for sale at the Cracker Jack.

The Dixie Drugstore at 1240 Loyola Avenue (now Simon Bolivar) continued to sell hoodoo supplies until 1984. Reverend William M. James’ St. Jude Altar and “novelty shop of religious articles” operated at 545 South Rampart from the 1960s until the mid-1980s. At present, several tourist-oriented shops in the French Quarter claim to sell “voodoo” items, but only Island of Salvation in the New Orleans Healing Center on St. Claude Avenue and the F & F Botánica and Spiritual Church Supply Company at the corner of Broad and St. Ann streets serve the multi-racial practitioners of the myriad spiritual traditions represented in New Orleans.

Preservation Efforts on South Rampart Street

The New Orleans Civic Center—the city hall, civil district court, and public library—have not aged well. The state office building was demolished because of extensive damage from flooding after Hurricane Katrina. The park is mostly visited by the homeless. Across from this depressing enclave lies what is left of South Rampart Street. Three of the four remaining buildings in the 400 block were owned by the Arlene and Joseph Meraux Charitable Foundation, an entity created in 1992 after the death of Joseph Meraux. In 1993, jazz historians and preservationists, alarmed about the deterioration of these structures, submitted a landmark nomination. The Downtown Development District declined to support this designation because it would conflict with the Growth Management Plan and “the need to stimulate the … Poydras/Loyola node as principal centers of modern, high-rise office and hotel development.”

Dr. Bruce Boyd Raeburn, director of the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University, wrote in support of the landmark nomination that “the 400 block of South Rampart Street represents one of the very best examples of early jazz ambience extant, and should be accordingly preserved.” John Hasse, curator of American Music at the Smithsonian Institution, declared that “there is probably no other block in America with buildings bearing so much significance to the history of our country’s great art form, jazz.” Despite this expert testimony, only in 2008 were the former Karnofsky Store, the former Iroquois Theater, and the former Eagle Saloon designated as New Orleans landmarks, subject to the jurisdiction of the Central Business District Historic District Landmarks Commission.

The Little Gem Saloon at the corner or South Rampart and Poydras has been put back into use as a fine restaurant and jazz club. In 2007 an entrepreneur bought the Eagle Saloon building from the Meraux Foundation. The new owner attempted to stabilize the structure but was unable to fulfill his promise to convert it into the “New Orleans Music Hall of Fame” he envisioned. An out-of-state entertainment corporation has expressed interest in restoring and reviving the 400 block of South Rampart but have not yet put forward any firm plans. The Karnofsky Store and Iroquois Theater buildings, still owned by the Meraux Foundation, remain crumbling and abandoned in a dreary no man’s land surrounded by looming skyscrapers and a vast expanse of parking lots. Perhaps these early 20th-century structures, so important to New Orleans’ African American jazz history, can also be restored and converted to some appropriate purpose. But sadly, the Cracker Jack Drug Store is gone forever.

—–

Carolyn Morrow Long is the author of Madame Lalaurie: Mistress of the Haunted House, a biography published by the University Press of Florida in 2012. The book was funded in part by a publications grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, which the author used to hire research assistants to trace Madame Lalaurie’s history in France. Long has also authored Spiritual Merchants: Religion, Magic, and Commerce and A New Orleans Voudou Priestess: The Legend and Reality of Marie Laveau, as well as an entry on Laveau for The Digital Encyclopedia of Louisiana, a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Long lives in Washington, D.C., and New Orleans.