Cultivating Understanding Through Children’s Books

As the state, country, and world contend with the over-representation of Black Americans among those dying from COVID-19, among those incarcerated for non-violent crimes, and among those experiencing violence from law enforcement officers, we are all reeling. The global response—through protests, boycotts, and social media—reminds us at PRIME TIME that we cannot forget what children are experiencing at this moment.

There are the personal experiences of children, like the six-year-old daughter of George Floyd, who have lost a father at the hands of police officers. There are the indirect, though still significant, experiences of children listening to the news in the background, overhearing adult conversations, or marching in the streets with their parents. These experiences call for direct and often difficult conversations like those at the heart of PRIME TIME Family Reading programs.

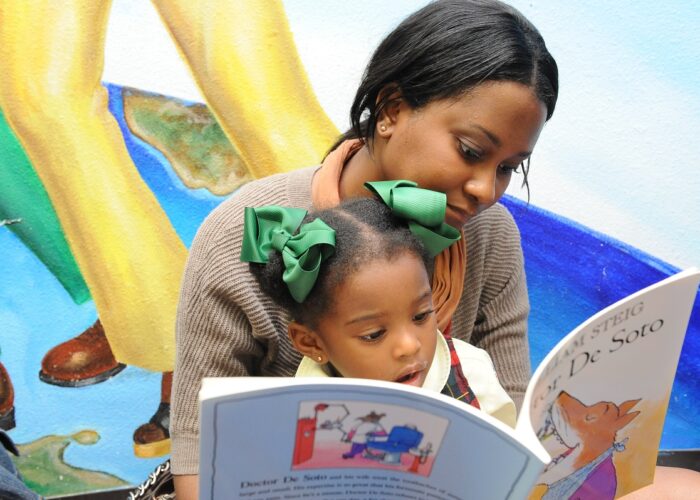

Reading and discussing quality children’s books and the humanities themes found within them can provide a launching point for conversations between care-givers and children that cultivate understanding. We hope that you will join us in those conversations online, and, more importantly, at home. We offer up the following PRIME TIME titles and themes to get the conversation started.

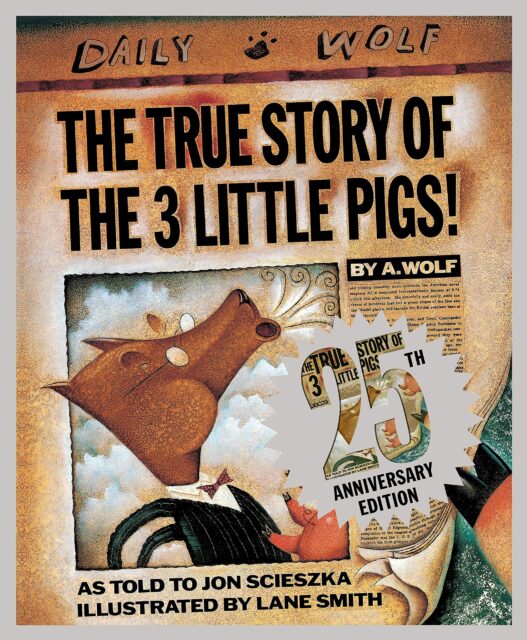

The True Story of the Three Little Pigs by Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith is the classic story of The Three Little Pigs but told from the perspective of Alexander T. Wolf. While baking a chocolate cake for his grandmother’s birthday, our protagonist realizes that he is out of sugar and decides to see if his neighbors might loan him some. Unfortunately, he is suffering from a cold, and accidentally blows the first and second Little Pigs’ houses down with powerful sneezes. Because the Little Pigs had died in the destruction, Wolf decides to eat them in order to not let a “perfectly good ham dinner go to waste.” By the time he gets to the third Little Pig’s house, Wolf is treated rudely when asking for a cup of sugar. Wolf is provoked into a sneezing rage. The third Little Pig reports Wolf to the police, who sentence him to ten millennia in prison.

Ask a child:

If you were a judge in a court, would you find the wolf guilty? Why or why not? What in his story would make you believe him or not believe him?

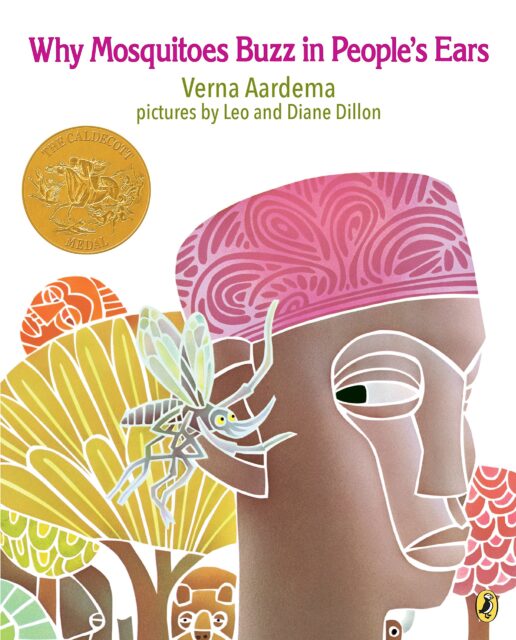

Why Mosquitoes Buzz in Peoples’ Ears by Verna Aardema

In this origin story, the mosquito lies to a lizard, who puts sticks in his ears and ends up frightening another animal, which sets off a panicked chain reaction. By the end, an owlet is killed and the owl is too sad to wake the sun until the animals hold court and find out who is responsible. The mosquito is eventually found out, but it hides in order to escape punishment. So now it constantly buzzes in people’s ears to try to discern if everyone is still angry at it.

Ask a child:

Who do you think was really to blame for the sun’s not rising? Who did the animals think was to blame? Do you think they were right? Why or why not? If you were on a jury and all the animals were arrested for the crime, which one (or ones) would you find guilty? Why?

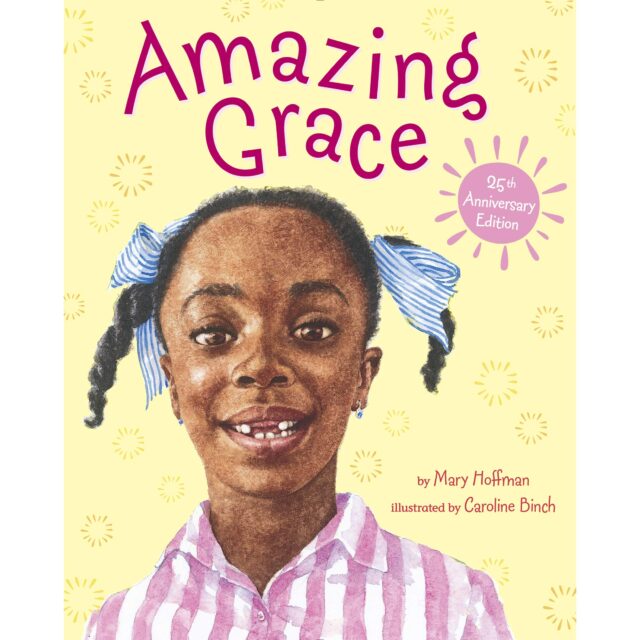

Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman

Grace loves stories—especially acting them out. So when her teacher tells the class that they will be performing a play about Peter Pan, she jumps at the chance to take on the leading role. But her classmates tell her she can’t play the role because she doesn’t look like Peter Pan. This doesn’t sit well with determined Grace, who, with the support of her family and a spark of inspiration from an actress who plays roles that don’t look like her, pushes past the judgments of her peers.

Ask a child:

Have you ever been told you can’t do something because of the way you look? How did that make you feel? What would you do differently if you had the chance to relive that experience?

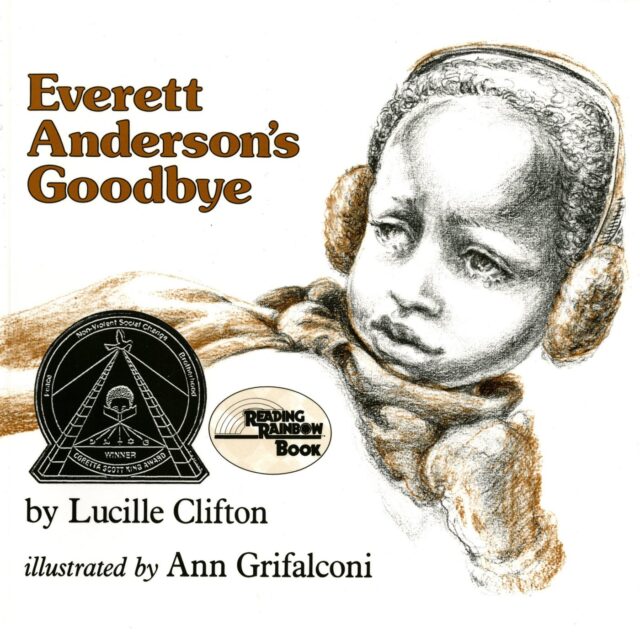

Everett Anderson’s Goodbye by Lucille Clifton

The winner of the 1984 Coretta Scott King Book Award, Everett Anderson’s Goodbye tells the story of a young Black American boy who is trying to come to grips with his father’s death. Everett moves through a range of emotions—denial, anger, despair—before coming to accept the loss of his father. The illustrations and spare text capture the vivid emotions tied to grief and also the difficulty of articulating those emotions through language.

Ask a child:

Why does Everett say he doesn’t love his family or candy or Santa Claus or his mother anymore? Does he mean it?

This is a sad book. Did you like it? Do you prefer sad books or happy ones? Why do you think authors write sad books?