Winter 1992

Dance for a Chicken

Grown men chase chickens, cross dress and receive whippings at Prairie Cajun Mardi Gras gumbo runs. It’s all a part of springtime rituals traced back to medieval Europe

Published: February 1, 2016

Last Updated: February 21, 2020

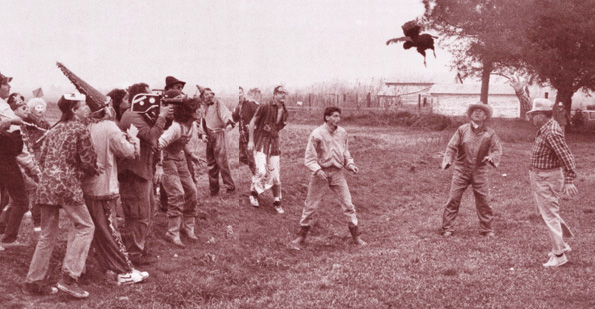

Photo by Barry Ancelet.

A farmer tosses a chicken to the crowd of Mardi Gras runners setting off a mad chase to grab the prized catch. In exchange for donating the bird, the farm owner gets a good laugh.

Rural Mardi Gras celebrations of the south Louisiana prairie differ greatly from their carnival counterparts in New Orleans or even Lafayette. Like them, they are pre–Lenten processional festivities steeped in traditions that harken back to the springtime fertility rituals of ancient Europe. But what sets the rural south Louisiana version of Fat Tuesday apart is the fete de la quemande, a medieval begging ceremony, later influenced by the frontier heritage of the Louisiana prairies, that have combined to form the uniquely Cajun “Mardi Gras run.”

A Community of Ritual

Many aspects of the Mardi Gras run in L’Anse Maigre, a community north of Eunice, are typical of those throughout Acadiana.

Led by a flag–bearing capitaine, L’ Anse Maigre’s colorful and noisy procession of masked and costumed men on horseback, followed by beer-stocked wagons, troop from house to house in the countryside asking for donated food or money in return for performances of dancing and buffoonery. The run participants are earnestly employed chasing chickens, the most valued offering, and they pride themselves on their ability to collect enough gumbo poultry to feed the entire community free of charge.

Cultural Catholicism binds the community, therefore no one is offended by the expected farm raids. Upstanding townsfolk work hard all year, but they also celebrate life abundantly because their faith teaches them that life has been redeemed. For them, Mardi Gras day provides the opportunity to let inhibitions go under the anonymity of a mask and with the aid of an endless and liberating supply of liquor.

At an organizational meeting before the Mardi Gras run, capitaine Wendell Manuel instructs his followers: “When you get to a man’s house … get off that horse and dance for him and beg to him … Do whatever you have to do to get his chickens or his sausage or his rice or his money … Anything we can do to get the goods for the supper.” Mardi Gras, after all, signifies a redistribution of wealth. Beneath its many layers of exotic behavior lies a serious message of survival which goes back to pre–Christian festivals and ancient rites of passage.

During this festival where everyone gives and everyone receives, which supports the egalitarian values of Cajun culture, humanity’s story of sharing is told over and over in the course of the day. In one of mankind’s oldest games of trying to fool your closest neighbors and best friends, these masked beggars symbolize anyone who may be hungry. The idea is that when they visit someone, those visited should share. Theft is part of the tension in the drama of this ritual play, especially when the runners feel that a particularly fortunate homeowner is not giving enough.

Questing songs are performed prior to the raids. Some communities require the runners to sing their version of the song in French, which discourages outsider participation. But other runs encourage outsiders to participate. Tourists have been courted in recent years, to the delight of merchants but to the dismay of traditionalists.

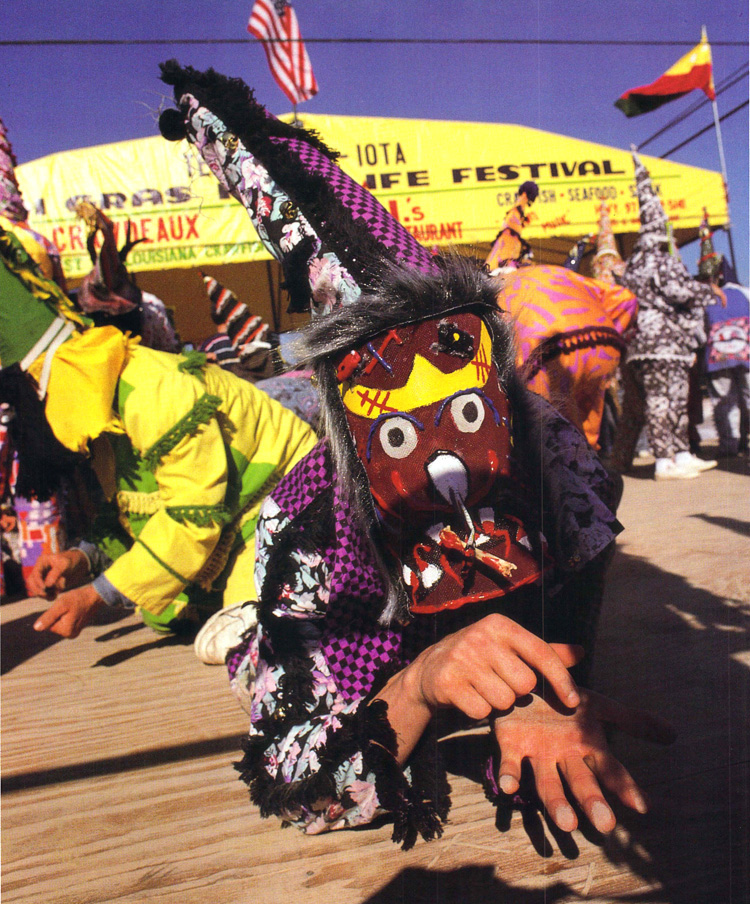

A masker imitates the Mardi Gras run gesture of supplication at the “Tee” Mamou-Iota Folklife Festival. Such fairs have kept tourists occupied in the cities while locals make their traditional gumbo run in the countryside with as little outside interference as possible. Photo by Phillip Gould

Impact of the Mainstream

The mainstreaming of American culture has indeed affected the long isolated Cajun culture. On the “Tee” Mamou women’s run, for example, traditional mock kidnappings of the homeowner’s children still occur, but in a less frightening fashion. Many participants lure the youngsters with candy and outstretched arms which demonstrates that their ideas of child rearing have changed. In years past, Cajun children were intentionally scared by the masked runners. For the smaller children these anonymously masked individuals served as reminders of the dangers that “lurked out there” and the value of staying close to home. For the older ones, Mardi Gras hastened maturity by teaching them to “face up” to the maskers.

Sadly, a couple of runs have almost turned into trail rides and seem more interested in returning to town on time for scheduled parades than fulfilling the event’s original mission. One run in particular lost its meaning when their culturally dysfunctional capitaine passed up a homeowner standing in his yard with chicken in hand which is an inconceivable act to most communities.

Tradition Endures

The “Tee” Mamou run (in western Acadia Parish) was not interrupted during World War II as it was in most other communities when all able participants were sent to war. Thus, the “Tee” Mamou group has maintained aspects of a very old begging tradition by using a gesture of pointing to the open palm. Centuries ago this distinguished carnival beggars in Western Europe from impoverished street beggars. Recent discovery and observation of the Hathaway Mardi Gras reveals similar and possibly older traditions. They have what they refer to as “our beggars,” who wield rolled burlap whips and lead the procession alongside the capitaine. Whipping traditions–ancient in origin and frightening to outsiders-have been preserved along isolated pockets of the Cajun prairie’s cultural edge west of Highway 13. Whipping has its origins in the pre–Christian festival of the Lupercalia, or the wolf festival, and was thought to promote fertility. In Kinder’s version of the Mardi Gras, participants walk the entire run and frequently pretend to flog each other with rolled burlap sacks, reminiscent of the processions of the flagellators who sought to atone for their sins in the Middle Ages.

Hathaway’s ritual beggars are blackfaced and are the first to approach a house. They dismount from their horses and confront the homeowners on their knees with hats in their hands and genuinely petition resident members for charity. This appears to be a vestige of the poor man’s carnival of the Middle Ages and may even have roots in the most widely celebrated festival of the Roman Calendar, the Saturnalia, where people masqueraded and blackened their faces.

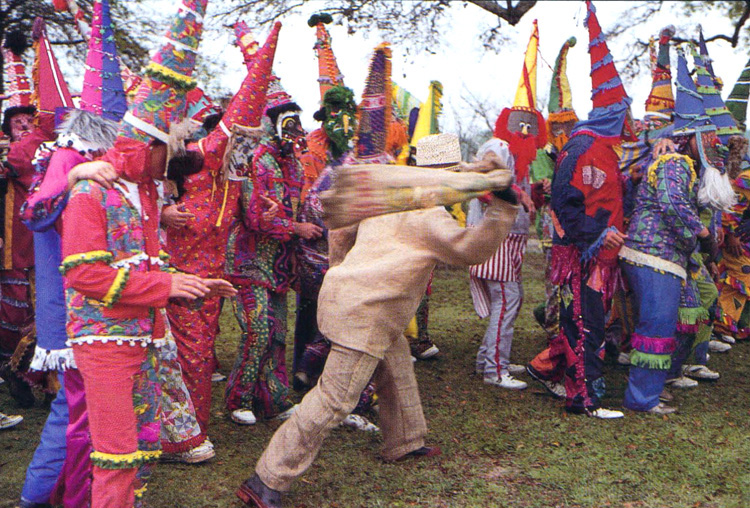

A “negre” whips “Tee” Mamou Mardi Gras run participants as they walk from house to house. The bizarre ritual derives from pagan fertility rites. Photo by Philip Gould

Role Reversals

With such bizarre rituals being carried out, it is easy to see why outside reporters, researchers and witnesses would invariably focus on the issues of racism, sexuality, and alcohol that pervade rural Mardi Gras runs.

Runners mask in blackface as negres and negresses. Drunkeness is part of the game, and men dance with men. Yet, it is important to understand such behavior in a cultural context.

Reversing social order and pretending to be black goes much farther back than the immediate roots of racism in the South. On the few remaining runs of the Black Creoles in southwestern Louisiana, participants frequently whiten their faces, and the earliest illustrations of African and Caribbean carnival include Blacks in white face. Similarly, men can be seen dressing as women and women as men. Young dress as old and old as young, rich as poor and poor as rich.

Concerning alcohol, many people forget that Mardi Gras is based on rites of passage that have for centuries used mind–altering drugs which loosen inhibitions and allows participants to “play the other.”

Parodying Current Issues

Communities preoccupied with preserving cultural continuity in costume provide the opportunity to walk back in time but have eliminated to some measure a core part of Mardi Gras: its ability to respond to current issues. In Eunice and Basile, parodying contemporary events is important. The social upheaval nature of Mardi Gras has always presented powerful commentary from the populace. There were effigies of Saddam Hussein and George Bush alongside modern versions of old theme costumes like the French paillasse (strawman) and the vieille femme (old woman) on the 1991 Eunice run. Demonstrating the frustration local people felt during the Gulf War, a life–size dummy of Hussein entitled “So Damn Insane” was hung by the neck with a can of “Bush” beer in his back pocket and was repeatedly assaulted. Another truck displayed Hussein’s decapitated head with a rooster (an old Carnival symbol of bravery and male sexuality) standing over him in triumph.

One of the strongest visual examples of the death and regeneration factor associated with Mardi Gras is the enacting of a birth, complete with a midwife, by men dressed as women, particularly the vieille femme. Such dramatic skits are performed along the run.

Possibly the most astounding folk drama happens in Hathaway. Here participant bonding and brotherhood is eminently exhibited when they are unsympathetically flogged by the beggars. Flogging is precipitated by their skipping a verse in the song, acting mischievously (which is expected of them), or when the homeowner pays to have them whipped. This latter action forces the capitaine to bring false charges on his troop and to order them punished. This is reminiscent of Saturnalia’s burlesque king who gave inane orders to his court of noblemen. Loud cries of ‘’I’m looking for some help” and “Where’s my brother?” issue from the accused as they are ordered to lie face down and take lashings prompt innocent participants to crawl over them and relieve their comrades’ sufferances by receiving the lashings themselves.

Yet, all successful runs have a core group of key players who have internalized the games rules and know instinctively what to do and how far they can push the boundaries that create the tension necessary to propel this disorderly contrivance towards its appeal for community equity.

Mardi Gras runners charge chosen farmsteads as soon as their capitaine has been granted permission from the homeowner. As the day wears on many runners are relegated to pickup trucks due to “drunk riding.” Photo by Phillip Gould

Just Rewards

The Eunice and “Tee” Mamou Iota Mardi Gras celebrations are both excellent examples of their respective towns coming together to demonstrate community pride and vitality in their traditions. Both have planned brilliant strategies to accommodate the flood of tourists and neighbors which they have courted.

Riders are welcomed back into town as surviving warriors to those townsfolk who did not participate in the ordeal but who will surely benefit at the night’s supper and dance. After the grand procession, most runners retire to a quiet spot to await their hard–earned supper, and justifiably they eat first. Some go home to rest or take their horses back to the barn before returning later for the masked ball which marks the final hours of revelry before the beginning of Lent.

All festivities stop abruptly at midnight and many of Tuesday’s rowdiest riders can be found on their knees receiving ashes on their foreheads on Wednesday.

—–

This article draws upon research conducted during a three–year collaborative effort by Barry Ancelet, Ray Brassieur, Carl Lindahl, Pat Mire, Maida Owens, and Carolyn Ware that culminated in Pat Mire’s film, Dance for a Chicken: Inside the Prairie Cajun Mardi Gras, funded in part by a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. This collaboration fueled other research projects including a book on the rural Mardi Gras by Ancelet and Lindahl and a dissertation on the women’s rural Mardi Gras by Ware.