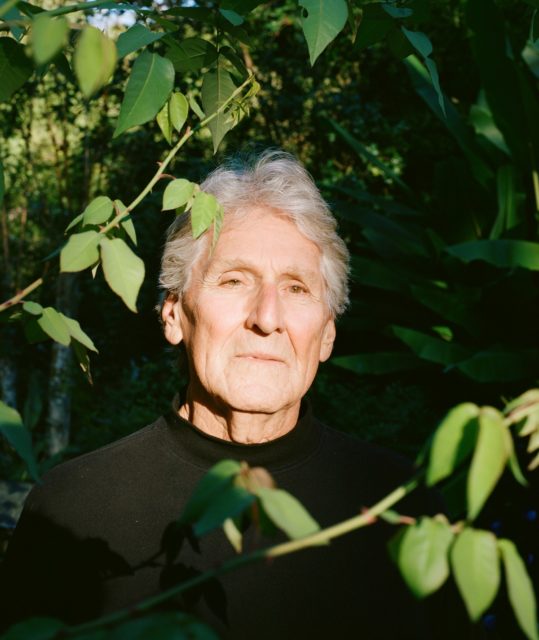

Darrell Bourque

The 2019 Humanist of the Year talks about music, memory, and the power of storytelling

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photos by Akasha Rabut.

Poet and activist Darrell Bourque has emerged as one of the most eloquent voices in contemporary Louisiana poetry. Long known as a poet tied to Acadiana and a master interpreter of place, his more recent work has addressed the Acadian Expulsion and larger themes of human migration. Off the page, he was instrumental in the recent drive to erect a statue of Creole music pioneer Amédé Ardoin and is a founding member of Narrative 4, a nonprofit that seeks to harness storytelling as a means to de-escalate conflict through recognition of shared humanity. We spoke with him recently at his Church Point home, which Bourque noted with pleasure was also his childhood home.

What changes in the area have you found most notable?

One of the most notable things is that presently we’re becoming a sort of suburb of Lafayette. Half of the population or more work in Lafayette, and that was not true when I grew up here. When I grew up here, it was a farming community. Where those nice houses are across the street were potato, cucumber, and cotton fields. The most significant change, I think, is that I live here as a writer, poet, and a kind of social activist. None of those things were even remotely connected to the boy who grew up here.

Do you have a sense of loss about these changes?

I have fond memories; my grandfather owned a large estate, and the only people I had direct, intimate contact with as a boy were my aunts and uncles and cousins who lived along this road. I was taught at a little school down the road, which was run by more distant relatives. I know a lot of what shaped me as a poet, my love of the land, my awareness about being good stewards of the land, came from those childhood experiences. But I also love the place where I live now. The people that I grew up with were to a large extent poor, and it’s become a kind of cliché, but those people never saw themselves as poor. Mobility was so different when I was growing up. This was a pretty remote area, and we didn’t have Lafayette to compare ourselves to, because we never went there.

What made being a poet or an activist or a writer seem possible for a farmer’s son?

Education. I like to jokingly say that my gap year was a weird but very important formative experience. I sold cheap shoes. I was a milkman. And those two jobs were really formative, because after that year I knew that I wanted something else. I figured out a way to get to Lafayette, to the university. I never see that as an obstacle, but as an important step towards what was to come.

You vary between forms in which you have a great degree of freedom and poems with a very defined structure. How does an idea lend itself to a form?

Nearly all of the early work, and probably all of the work until the last three or four publications, was in a looser, freer form. I was studying Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson and those marvelous rebels who believed that the poet’s responsibility was to create form and to let the form emerge from the idea or the spirit of the poem. That guided me for a long time. There’s such an attractiveness to that free, raw, wild American poetry from the beginning of the century. You can explore that and you go where you want to go with that fuel, but then you discover the wild possibility of working inside of form. That came to me much later. While early on I was loving the formalism, for instance, of a Shakespeare, I couldn’t do it yet. When you can’t do one thing, you do something else, and then doing something else with focus and dedication and love might lead you to be able to work inside of what you might earlier have found stifling and too restrictive. I think if you’re a poet of any worth, you try to find the new and the fresh inside the traditional. I have for the last few years almost exclusively worked in the sonnet form, but I created a particular sonnet form that I work in.

What’s a Bourque sonnet?

A Bourque sonnet is a kind of broken sonnet. When I started working in the sonnet form, I was exploring the possibilities of the historic poem, and I was interested in the migration of the Acadians into Louisiana. By a stroke of luck, I began to really look at the Italian sonnet, the Petrarchan sonnet. That’s a sonnet that’s shaped by an octave and a sestet that are placed against each other and have an energy and dynamic that work together. I knew that Petrarch created a revolution, because to a large extent what he was doing with his particular sonnet was saying that the little stories mattered. Nearly all of his sonnets are about this unrequited love for this young woman, Laura. He abandons the idea of writing about the heroic and decides to write about the personal and the human. It’s a huge revolutionary act because it creates humanism. All of a sudden, all of our stories become possible. I was studying that at the time that I was thinking of the historical poems I wanted to write about the expulsion of the Acadians, and I created a sonnet form where I break the octave into an opening and a closing four lines. It’s not a resolution at all. I thought that was appropriate to write the history of a people whose history was broken.

You’ve specifically begun writing ghazals [a form from Arabic poetry comprising linked couplets] about migration. What drew you to that form for this topic?

When I got to the book of ghazals and began to work in that antique Arabic form, I thought it was the perfect form for contemporary audiences, because even if we write in English, we no longer live in an exclusively English-speaking world. I know that if I introduce a reading as a sequence of ghazals that I’m going to have to explain it. That gets us out of the confines of thinking that are at the core of why immigration is such a hard issue. It’s always about a fear of the other and protection of inclusiveness, which I don’t believe in.

We’re at this profound crossroads where we’re being asked to figure out how we define the world we live in, and who it belongs to, and what parts of it belong to certain people and not to other people. We’re forced to challenge ideas about ownership and identity and culture. And so for me, this last book in many ways is the most exciting book that I’ve written, because I’m writing in a form that I myself am not terribly familiar with, and that didn’t come to me until I got the idea for the sequence of poems. In the ghazal each of the couplets is almost a little poem in and of itself. There has to be a relationship of one couplet to another, but each is distinct and has its own identity. I love that connected to the idea of immigration.

Remembering our stories is an essential, profoundly important activity. Without the stories, we diminish.

How did you come to be involved in the project to commemorate Amédé Ardoin?

In telling the story of the Acadians I learned about the culture that we had lost, and one of the things that I discovered in writing Megan’s Guitar and Other Poems from Acadie was that we had not only lost or pushed away an important part of our history, but we had also been manipulated to not even see an important part of our indigenous culture. One of the ways we dealt with poverty, that we dealt with being “other,” and that’s an essential part of the Acadian experience, is to create an other. In rural Acadian, Creole communities like these, the other other becomes the Creole, or the black people that we grew up with. I was not capable of understanding what I had lived until I was in my sixties and seventies. As a writer and as a historian and as a poet, I felt that I had to explore that experience, that loss. I had to explore why and how we could live inside of this culture and not respond to a whole group of people that we lived with.

I began to listen to Cajun music more, and the more I listened, the more I realized that Cajun and Creole music were so closely related to each other. I began to simply be aware that there was another history that needed to be told. I discovered, in a way, the story of Amédé Ardoin, and then another whole world opened up, because his story is to a large extent a story about segregation, about hatred, about racism, but all of those things are not who he was. He emerged from that as a kind of heroic figure, because if you look at what we know of his life, and if you look at the lyrics of his songs, he’s a poet and a troubadour, and he finds a way to do what poets and troubadours do. That’s to live authentically. To me, that’s the definition of a hero.

Tell me about the Narrative 4 storytelling project. Why do you see storytelling as having this connective power?

One of the things that we talked about earlier on, that I think is still at the heart of Narrative 4, is that remembering our stories, and transmitting them, not only creates civilizations but sustains them and allows one civilization to give birth to another. If we were to quit telling our stories, we would become isolated, which would have a weathering effect on what’s possible for us as human beings. Remembering our stories is an essential, profoundly important activity. Without the stories, we diminish. Narrative 4 takes this idea of the importance of the human story and then takes it further to this idea of the importance of story exchange.

The primary activity in Narrative 4 is to create settings for different groups of people to exchange stories, and part of their mission is to go into places that are in conflict, where they mostly work with kids. I tell you a story that’s profoundly important to me as a human being, and then you tell me a story that’s profoundly important to you. Then we switch, and in first person, we tell each other. I tell you your story in first person, but as I heard it. You get to hear your story as it’s reflected in a first-person account by someone else. And immediately what you will experience, nearly always, is that yes, that is your story. The identity merger that that produces is really effective.

I connect this to one of the stories about the origins of poetry. Zeus goes to Mnemosyne, Memory, and says to her, “I’m a pretty important dude, and I’m doing lots of really cool things, but what will it amount to? How will I be remembered?” She says to him, “If you sleep with me for nine nights, I’ll tell you.” So she sleeps with him for nine nights, and she [gives birth to] the nine Muses. She says to him, “You will be remembered in history, in music and dance, and all of the humanities . . . You’ll be remembered in erotic poetry. You’ll be remembered in sacred song, and you’ll be remembered in songs about the environment.” And there you are.

What else are you working on now, and what comes next?

This morning, my wife Karen and I finished installing glass work she did for Christ the King Church in Bellevue, a small community in south St. Landry Parish. She and I are parishioners and volunteers there. I will be doing a reading-performance with Creole accordionist Mary Broussard at the Books Along the Teche book festival on April 5, and I was invited by the Iberia African-American Historical Society to create a poem for the dedication of a historical marker for Dr. Emma Wakefield-Paillet of New Iberia, Louisiana’s first African American female physician.

My book of sonnets on Henriette DeLille with paintings by Shreveport artist Bill Gingles should be released early in the year, and I am completing Migraré, a book of ghazals also with paintings by Gingles, to be published later in 2019.

I am working with St. Landry Parish tourism to create an annual event to honor Amédé Ardoin, and I have started negotiations with Pete Gregory at the Creole Heritage Center at Northwestern State University to create collaborative events for the various Creole populations in the state. I also continue to work with Grand Coteau’s Festival of Words and NUNU Arts and Culture Collective, and I will continue to serve on the Ernest J. Gaines Center Board and work with Gaines Center programming.

To read new poems from Darrell Bourque, click here.

Darrell Bourque is professor emeritus in English (University of Louisiana at Lafayette), a former Louisiana Poet Laureate, and recipient of the 2014 Louisiana Book Festival Writer Award and the ULL Center for Louisiana Studies James Rivers Award. He is a founding member of Narrative 4, an international story exchange, and a co-founder of the Amédé Ardoin Project. His poetry publications include Megan’s Guitar and Other Poems from Acadie and the forthcoming From the Other Side: Henriette Delille.

—

Celebrate Darrell Bourque and all of the 2019 Humanities Award winners on April 4 at the Bright Lights Awards Dinner in Lafayette. For more information and tickets, visit www.leh.org/brightlights.