De-Satch-uration

Louis Armstrong’s complicated relationship with New Orleans

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

Louis Armstrong House Museum

African American photographer Villard Paddio took this photo of Armstrong with his orchestra, directed by Zilner Randolph (second from right), at the Suburban Gardens in the summer of 1931.

After a weekend of such “Satch-uration,” I boarded my flight back to New York and resumed my day job: as director of research collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum—in Queens, New York. I’m in charge of the Louis Armstrong Archives—located at Queens College. On the anniversary of Armstrong’s passing, I paid my respects—at Flushing Cemetery in Queens. As I wrote the first draft of these words, I was also planning the opening of the state-of-the-art Louis Armstrong Center, which opened in the summer of 2023 directly across the street from the Armstrong House—in Corona, Queens.

I am constantly asked why the Armstrong Museum is in Queens, why he is buried in Queens, why I teach an Armstrong course in Queens—and not in New Orleans. The answers are complicated, though not exactly surprising as one digs deeper into the complex relationship between Louis Armstrong and his hometowns.

Armstrong was a product of the South. In an unedited manuscript for Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans, he describes his first run in with “James Crow”: he was five, too young to read a “For Colored Patrons Only” notice, and got scolded by a friend of his mother. When Armstrong innocently asked why he couldn’t sit where he wanted, the woman snapped, “Boy, don’t ask so many questions, and SIT DOWN DAMIT.” In his formative years, he had run-ins with the police, whom he knew as “the peelers”—“Because they were known to ‘Peel’ your head, when they arrest’d you.” He witnessed lynchings. He was even chased by an angry white mob after heavyweight champion Jack Johnson knocked out “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries in 1910.

On one of Louis’s first nights back in New Orleans in 1931, he visited his old boss from his brass band days, trumpeter Oscar “Papa” Celestin. Lil Hardin Armstrong is standing next to Louis; they would separate during this trip and eventually divorce in 1938. Louis Armstrong House Museum.

But Armstrong didn’t dwell on the negative. “Now, I must tell you that my whole life has been happiness,” he claimed in a 1970 letter to writer Max Jones. He seemed to have nothing but fondness for the city that raised him. “I’ve had some great ovations in my time, had beautiful moments,” he said to Life magazine reporter Richard Meryman in 1965. “But seems like I was more content, more relaxed growing up in New Orleans.”

Armstrong was born in a small wooden-frame home at 723 Jane Alley and spent most of his formative years living with his mother and sister in the “Battlefield” area of Liberty and Perdido Streets in the Third Ward. He left home in July 1922 to join King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band in Chicago, making his first recordings on April 5, 1923—one hundred years ago. One of the tunes recorded at that first session was an Armstrong-Oliver composition titled “Canal Street Blues.” Forty-eight years later, on March 15, 1971, Louis Armstrong performed in public for the last time at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, ending his show with an autobiographical take on “When the Saints Go Marching In” titled “Boy from New Orleans.”

Over the course of his career, he never stopped singing and performing songs about his hometown: “New Orleans Stomp,” “Where the Blues Were Born in New Orleans,” “Perdido Street Blues,” “King of the Zulus,” “The Mardi Gras March,” “Basin Street Blues,” “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans,” “Farewell to Storyville,” “Bourbon Street Parade,” and perhaps most famously, “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans.”

He also never stopped writing about it, publishing two autobiographies in his lifetime, Swing That Music and Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. Other autobiographical manuscripts about those years were published posthumously. Letters have surfaced in recent years, held in archives such as the one at the Louis Armstrong House Museum and the Hogan Archive at Tulane, many bearing his standard sign-off, “Red beans and ricely yours.”

Those years taught him everything he needed to know about music, about food, about race, about women, about work, about life.

And yet as soon as he left for Chicago in 1922, he never even entertained the thought of moving back. What happened?

As Armstrong himself put it during a 1970 appearance on the Dick Cavett show: “I done got Northern-fied and forgot about a whole lot of that foolishness down there, you know?”

Between the summer of 1922 and the summer of 1931, Armstrong spent almost all of his time in cities with thriving Black arts scenes: the South Side of Chicago, Harlem in the midst of its “Renaissance,” and Central Avenue in Los Angeles. He became a star, indulged in a love of fashion, made good money, even encouraged and befriended many white musicians who fell under his spell.

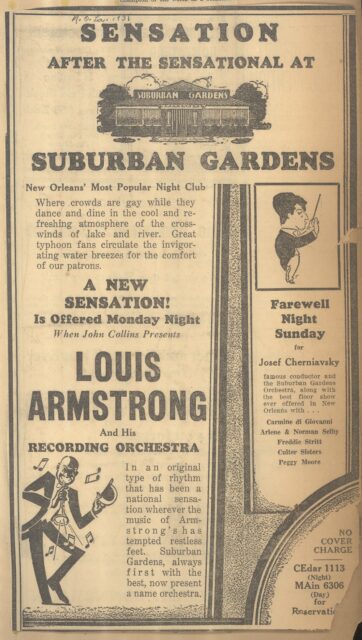

Armstrong spent the summer of 1931 performing at the Suburban Gardens in Jefferson Parish. This advertisement was one of many newspaper clippings and mementos he personally saved in an oversized scrapbook. Louis Armstrong House Museum.

When he visited home for the first time in June 1931, he was reminded of that “foolishness” almost immediately. The only place that would book Armstrong was the Suburban Gardens, an establishment with a whites-only patron policy. On his first night there, a white radio announcer took one look at Armstrong, said, “I just can’t introduce that n***** on the air,” and walked off.

Armstrong wound up spending three months in New Orleans that summer, which was probably enough time for him to make the decision that he would never live there again.

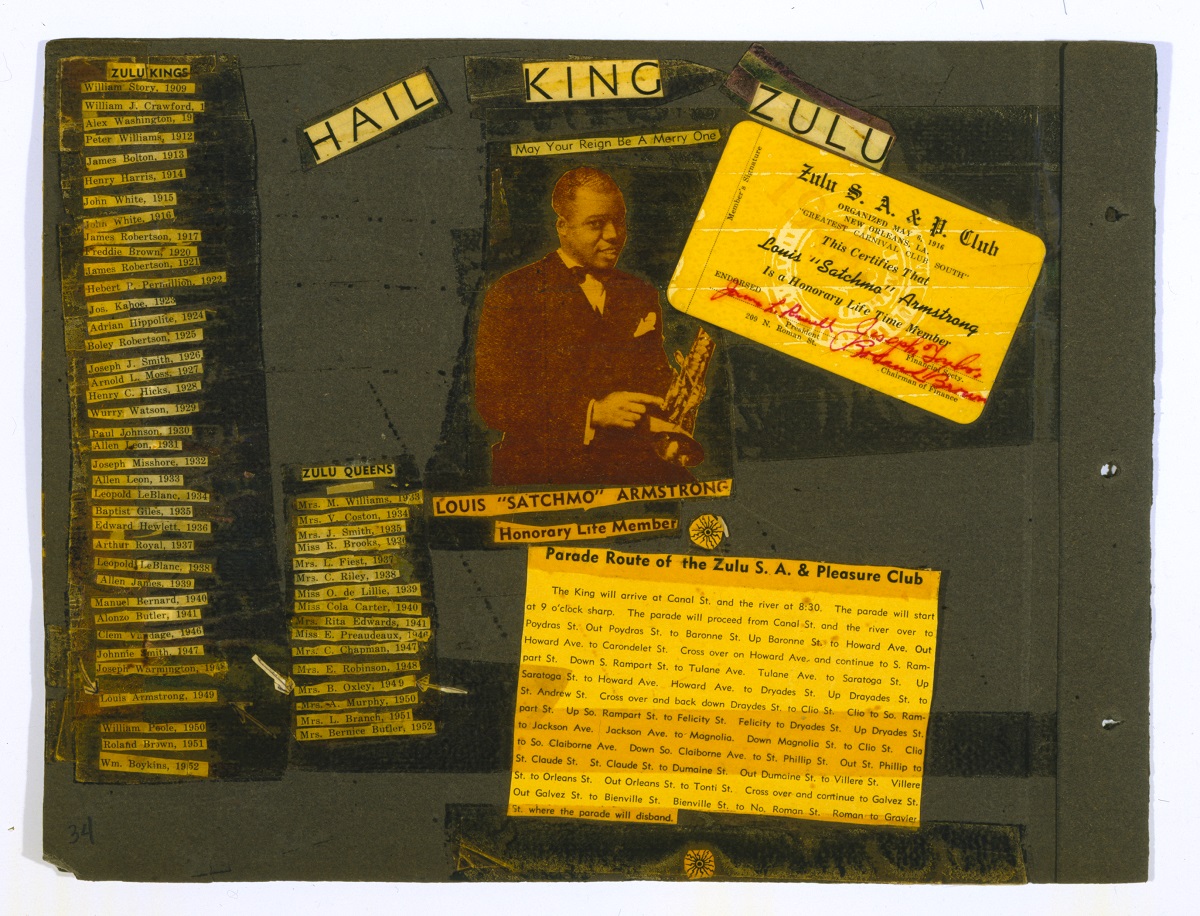

He did continue to perform in his hometown regularly throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, most famously serving as Zulu King at the 1949 Mardi Gras. “There’s a thing I’ve dreamed of all my life,” he said to Time magazine just before that year’s Carnival festivities began, “and I’ll be damned if it don’t look like it’s about to come true—to be King of the Zulus’ Parade. After that I’ll be ready to die.”

On March 1, 1949, Armstrong was awakened by a group of Zulu members, who had arrived to get him into costume: grass skirt, gold slippers, gold robe, black turtleneck and tights, and blackface makeup. As Armstrong well knew, the Zulu costume was a Black Carnival tradition that, among other things, lampooned the white Carnival traditions, and most New Orleanians were aware of that, too—but outside of the city, it was a different story. Black newspapers in other regions were already critical of artists such as Armstrong and Nat King Cole for continuing to tour the South, and the photos were not well received. “King Zulu Reigns (Ugh!)” a headline read in the Pittsburgh Courier, alongside photos of the trumpeter in blackface. “The grotesquely made up Armstrong, who couldn’t be recognized by even his most avid fan, struck a queer note,” the Chicago Defender complained. “He is one of the few top flight Negro entertainers who has not announced that he will bypass the Crescent City because of its Jim Crow. Maybe it’s because it’s home.”

But after a one-night concert performance at the Municipal Auditorium in 1952 and one quick television appearance on the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1955, Armstrong finally decided that he, too, would “bypass the Crescent City because of its Jim Crow.” Act 579 of 1956 of the Louisiana State Legislature effectively prohibited integrated bands from performing in public. Armstrong’s small group, the All Stars, had been integrated since its inception in 1947 (“Ain’t nobody gonna call me intolerant,” he once said).

Though Armstrong usually chose not to comment publicly on issues of race, he did not hold back on this matter. “After all, we have two white boys in our band, so if New Orleans don’t allow it, although it’s my hometown, ain’t no use of me going there to play,” Armstrong told Al “Jazzbo” Collins during a radio interview in April 1957. “I mean, ’cause, we play together everywhere else.” One year later, Armstrong vented to San Francisco newspaper reporter Albert Colegrove, “What you got to realize, all restrictions and things, such as the restrictions in New Orleans now, they don’t want white boys and colored playing together. The people that made those laws don’t know nothing about music.” Armstrong grew serious as he insisted, “And don’t take that out—quote that! And until they straighten it, I don’t go to New Orleans.”

Armstrong designed this collage in one of his scrapbooks in 1952, cutting out the names of all Zulu kings and queens, including information on the Zulus’ parade route, and even affixing a card naming him an “Honorary Life Member” of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Louis Armstrong House Museum.

Matters came to a head in 1959, when a Louis Armstrong Playground was to be dedicated in Jefferson Parish. City officials wanted Armstrong to perform at the ceremony with his band, but he refused, telling a Times-Picayune reporter that he would not return to his hometown until he was “received without racial distinction . . . I’m accepted all over the world, and when New Orleans accepts me, I will go home . . . I’m accepted in satellite nations behind the Iron Curtain, even before they see me . . . I feel bad about it, but will nonetheless stay that way.”

Armstrong’s words were promptly criticized back home by O. C. W. Taylor, an African American print and broadcast journalist who also was a prominent public school teacher and principal. Taylor told the Associated Negro Press that Armstrong “was always contented to return a grinning, ape-like Sambo and help keep the Negro in his ‘Uncle Tom’ status. Maybe New Orleans does not accept him. New Orleans prefers to read about him, to remember him as a successful trumpet player . . . maybe New Orleans is rather tired of having him come down and lower the level of the Negro group.”

Armstrong was willing to grant Taylor his wish. “I don’t care if I never see the city again,” he said. “Ain’t it stupid? Jazz was born there, and I remember when it wasn’t no crime for cats of any color to get together and blow.” He told British writer Max Jones, “I ain’t going back to New Orleans and let them white folks be whipping me on my head.”

Louisiana’s attorney general, Jack Gremillion, simply told reporters, “The law exists and as long as it does I’m going to enforce it.”

In his concerts, Armstrong continued to perform “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans” but now as part of a medley—paired up with “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.”

As the 1960s progressed and the civil rights movement gathered more steam, Armstrong came under more accusations of being an “Uncle Tom.” He bristled at the notion, telling Ebony in 1964, “I can’t even play in my own hometown, ’cause I’ve got white cats in the band. All I’d have to do is take all colored cats down there and I could make a million bucks. But to hell with the money. If we can’t play down there like we play everywhere else we go, we don’t play. So this is what burns me up every time some damn fool says something about ‘Tomming.’”

In his concerts, Armstrong continued to perform “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans” but now as part of a medley—paired up with “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.”

In 1964 New Orleans was looking to build a new police complex. The plans would require the demolition of the home Armstrong was born in at 723 Jane Alley. The New Orleans Jazz Club, led by Dr. Edmond Souchon, came up with a plan to pay to move the entire property to the New Orleans Jazz Museum at 1017 Dumaine Street, but Mike Badalamenti, head of the Bal Construction Company, grew anxious. “So last Thursday the firm burned and leveled the Armstrong birthplace,” the Louisiana Weekly reported. “Only a little mound of bricks and burned timber remained last Thursday. The next day, even that had disappeared.” Badalamenti simply told the press, “It had to be cleared.”

In February 1965 members of the New Orleans Jazz Club visited Armstrong in his hotel room in Memphis. The conversation was tape-recorded and is now held in the collection of the Louis Armstrong House Museum. “Louis, did you hear of the trouble we had?” Jazz Club President Helen Arlt asked Armstrong, before explaining the details of what happened to his boyhood home.

“Yeah, I heard about it,” Armstrong responded. “The main thing, I mean, what makes me feel good, is you tried. Remember that old saying, ‘Lord, how I tried.’”

“Well, we did,” Arlt said. “And we wanted to make it a whole little museum.”

“But I understand,” Armstrong said, sounding a bit sad but not surprised. “You can’t do the impossible. But I appreciate the efforts that you did and tell all the members I’m happy over that much.”

The members of the Jazz Club were there to convince Armstrong to perform in New Orleans again, now that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made the old segregation laws obsolete. And Armstrong did just that, returning for a one-nighter at the Loyola Field House on October 31, 1965. Thousands of fans, friends, musicians, and other important folks from his life—including members of the Karnofsky family, for whom Louis worked as a young man, and Peter Davis, who taught Louis how to play cornet at the Colored Waif’s Home—showed up to welcome Armstrong home for the first time in a decade. Also present was O. C. W. Taylor—brandishing a “Welcome Home” plaque, complete with Taylor’s own lyrics, set to the tune of “Hello, Dolly,” pleading, “don’t leave us anymore.”

But twenty-four hours later, Armstrong did indeed leave, to fly to Houston. He would return two more times to play concerts, but after a performance at Jazzfest ’68, Armstrong never set foot in his hometown again. A year later, sick and depressed, in intensive care at New York’s Beth Israel Hospital, Armstrong poured his bitterness into a handwritten manuscript, complaining that “New Orleans was so disgustingly segregated.”

Armstrong now had mortality on his mind. Once out of the hospital, Armstrong was asked if he wanted a New Orleans funeral. “Well, I don’t know,” he said, in an interview with Cadence magazine in February 1969. “[My wife] Lucille’s got a family plot for all of us. I got a little spot there so I think that’s where I’ll be buried—Flushing. Just let ’em have their ball in New Orleans and we’ll get drunk up here.”

But as his health and mood improved the following year, Armstrong changed his tune. “They going to enjoy blowing over me, ain’t they?” he said to the New York Times in July 1970, contemplating what his New Orleans funeral would entail. “Cats will be coming from California and everywhere else just to play.”

Armstrong in full Zulu King regalia, including blackface makeup, at the 1949 Mardi Gras. Louis Armstrong House Museum, Jack Bradley Collection.

He passed away July 6, 1971. Lucille presided over a somber ceremony at Corona Congregational Church in Queens—without any music. New Orleans made up for it, hosting a raucous tribute complete with brass bands, climaxed by trumpeter Teddy Riley blowing “Taps” on Armstrong’s Waif’s Home cornet. A Jet magazine headline proclaimed, “Satchmo’s Funeral ‘White and Dead’ in New York, But ‘Black, Alive and Swinging’ in New Orleans.”

Lucille Armstrong had no regrets burying her husband in Queens. “Except for his sister, Beatrice, and his half brothers, Henry and William Armstrong, he has nothing in New Orleans,” she said to Jet magazine at the time of his passing. “He hasn’t lived in New Orleans since he was 19, and although he was born there, he considered New York his home. After all, he spent 40 years of his life here.”

With Armstrong deceased, New Orleans began the long journey of reclaiming him, beginning with the opening of Armstrong Park in 1980—a project that required the demolition of a good chunk of the predominantly Black Tremé neighborhood to complete. Perhaps this controversial act best exemplifies the “messy” love-hate relationship between the city and its favorite son.

But though he did not mince words when disappointed by its actions, Armstrong never disavowed New Orleans as the place that made him who he became. In that 1965 conversation with the New Orleans Jazz Club—after not visiting the city for a decade, having just learned that his boyhood home was destroyed—Armstrong still said of New Orleans, “My heart’s there.”

“They say, ‘Where would you live?’” Armstrong continued. “I said I don’t care where, I’m born in New Orleans, that’s my hometown. That’s it. I don’t care where, I’ll go to Guadalupe, wherever it is—[I’m a] New Orleans boy, and that’s it.”

Armstrong knew what it meant to miss New Orleans, to love New Orleans, to celebrate New Orleans, to be hurt by New Orleans, and to hate New Orleans—but through it all, he knew that in many ways, he was New Orleans, with all of its complexities.

And over fifty years after his passing, he’s still New Orleans.

Ricky Riccardi is director of research collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum and author of What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years and Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong. In 2022 he won a Grammy Award for Best Album Notes for The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia and RCA Studio Sessions 1946–1966. For more on the Louis Armstrong House Museum and Center, visit louisarmstronghouse.org.