Fall 2024

Dreams of Zines

Underground publications offer a window into Louisiana communities

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Caroline Ziegler

Zine artwork by Caroline Ziegler.

It was a warm, cloudy afternoon when Adrienne Lewis walked through a nondescript storefront on Government Street in Baton Rouge’s Mid City and into a zine library. Dozens of zines—small self-published pamphlet-style booklets with text and images—were scattered across tabletops, and a handful of people were already comfortably settled down and reading.

Lewis had moved to Baton Rouge from Brooklyn, New York, only a few weeks earlier to attend Louisiana State University. Finding the zine library—a pop-up called Screaming into the Future, hosted at Groworking Space—was a relief. “When I visit a new place, I always try to find where the zines are,” Lewis told me over coffee. “Every time I find zines, I find my people. There’s something about the DIY mentality. The type of people who take the time to create a zine and share it tend to be more generous, more in tune to their communities.”

It was a zine, in fact, that led Lewis to the zine library. On her first day on campus, she found a zine at LSU Libraries that was promoting an exhibition and research tool. From the zine, Lewis visited the website, which in turn listed the zine library as a local resource.

Lewis’s experience—finding zines and finding community through zines—is part of a decades-long tradition. Most histories trace zines to the counterculture movements of the 1960s and ’70s. Definitions vary, but in general, a zine—the term originates from the shortening of the word “magazine”—is a self-published, inexpensive way of sharing information, art, opinions, comics, humor, poetry, and, really, anything else. The expansive nature of zines is itself a feature of the do-it-yourself ethos of the medium.

Fixing a more precise definition to zines is difficult because one of their defining qualities is variability. Zines can look very professional, with high-quality images and well-designed text layouts. They can also be handwritten on paper folded in half and hastily stapled together. Beyond format and appearance, they can be about anything. Perzines (“personal zines”) tend to contain personal stories, insights, and viewpoints of the author; fan zines tend to focus on a single subject, such as a type of music or movie, and contain in-depth information on that subject. The zine library at Barnard College, one of the largest collections of its kind, defines zine as “a DIY subculture self-publication, usually made on paper and reproduced with a photocopier or printer. Zine creators are often motivated by a desire to share knowledge or experience with people in marginalized or otherwise less-empowered communities.”

For many zine makers, it’s the power to communicate on their own terms that make zines appealing. Zines offer more agency than social media posts, which can be shared quickly but offer little control over who sees them, or formal publications, subject to the whims of gatekeepers like reviewers and editors; zines offer a world of variation in a cultural moment that seems increasingly digital and visually homogenized. The decision to share zines, and with whom, can be a very personal one. Because zines can be made by anyone, on any topic, it’s not uncommon to see enthusiasm valued over formal production skills. As Bill Brent, long-time zine maker and collector, writes in the fourth edition of Make a Zine!: Start Your Own Underground Publishing Revolution: “Passion gets you through times of no technique better than technique gets you through times of no passion.”

Though there are plenty of digital zines, the physical nature of printed zines continues to hold special relevance. The limited run of print zines allows creators to tailor their art for specific events and timeframes. “The first zine I ever made was when my grandmother passed away,” Erin Segura, an instructor in French Studies at LSU, told me. “I wanted to make a zine to give to people at the funeral, and it felt so therapeutic.”

Segura’s appreciation of zines as tools for commemoration and communication prompted her to integrate them into her Louisiana French class in 2023. Students fan out across Louisiana to interview native Louisiana French speakers, and then they create a zine to combine the interview transcript with various visual elements, including pictures and illustrations. Before adding zines to the class, Segura relied on recordings of the interviews, uploaded to YouTube, to showcase the students’ work. While the videos have been well received, Segura notes that people need to know to go find them. Physical zines, on the other hand, are easier to discover serendipitously. “You see one at a bookstore, you pick one up, you stick it in your bag. I love how consumable they are. It’s potentially a way to get Louisiana French in front of people who otherwise wouldn’t see it.” Zines are also easier to share with the interviewees. “Whereas with videos, we could send the interviewees a link or even invite them to a viewing, but it’s not always easy for them to travel [to the viewing]. But with zines, we can just mail them a copy. It’s much easier.”

In addition to all the other benefits, there’s one large hope that Segura has for the zine project. “For so long, Louisiana French has been thought of as this language that couldn’t be written,” she said. “That is a stigma that is hard to break, and I think that it’s important to get more written Louisiana French in front of people’s eyes, because that’s something that legitimizes the language.” With zines in Louisiana French, Segura hopes, people will understand that “you can create things with written Louisiana French. You can read it. You can write it. You can consume it that way. I’m excited to see where this project might take that.”

Across town, another class in Baton Rouge is experimenting with zines. Mary Clinkenbeard, assistant professor of English at Southern University, is using zines in her freshman composition course. Students in Clinkenbeard’s course are tasked with creating zines for a process analysis essay, in which they explain how to complete a task or reach a goal of their choosing. “I wanted students to think more clearly about their audiences,” Clinkenbeard said. “When writing more traditional essays, the audience is just me.” When they make zines, however, they’ll be sharing them with their classmates. This is a motivation to think much more carefully about how their words will be received by different audiences.

Clinkenbeard’s zine assignment also introduces physical restraints that her students rarely encounter. “I wanted to do a project that was tied to a physical format,” Clinkenbeard explained. This is the only assignment in which students print anything out, and have to consider physical formats and designs. Students consider how images and text will occupy the same pages and how to maintain a narrative flow as the audience flips through the document. At its best, the intimate nature of the format is reflected in the message. “One student,” said Clinkenbeard, “wrote about mental health in various assignments. In traditional essay format the author held the topic at arm’s length. In the zine, however, they wrote in a more grounded and personal way.” Clinkenbeard noted that while most students weren’t familiar with zines when the assignment began, several have since reported seeking out zines on their own.

Clinkenbeard’s students are discovering what so many others have before them: zines are catalysts for community-building. Gabriella Lindsay uses zines exactly for that reason. She started the zine Cher in October 2023. “It’s a queer Louisiana writers and art zine,” Lindsay explained to me. “It’s booklet form. Three sheets printed front and back and folded, so twelve pages in all.” It’s also print-only. “We don’t have any digital copies, we’re not on social media. The hope is to create community and let people discover it through word of mouth.” Lindsay’s motivation for starting Cher is to give a platform for the people she personally knew. “I kept meeting queer people who were so talented in both text-based and [visual] art, and I thought it would be such a cool thing to come together and put our art and writing together.”

Some zines, like Lindsay’s, that exist to build community find their way into collecting institutions such as libraries and archives. Across Louisiana, zine collections are held not only in DIY spaces but also at Amistad Research Center and Tulane University Special Collections in New Orleans, LSU Hill Memorial Library, and East Baton Rouge Parish Libraries Special Collections. And some librarians are keen to use zines for outreach.

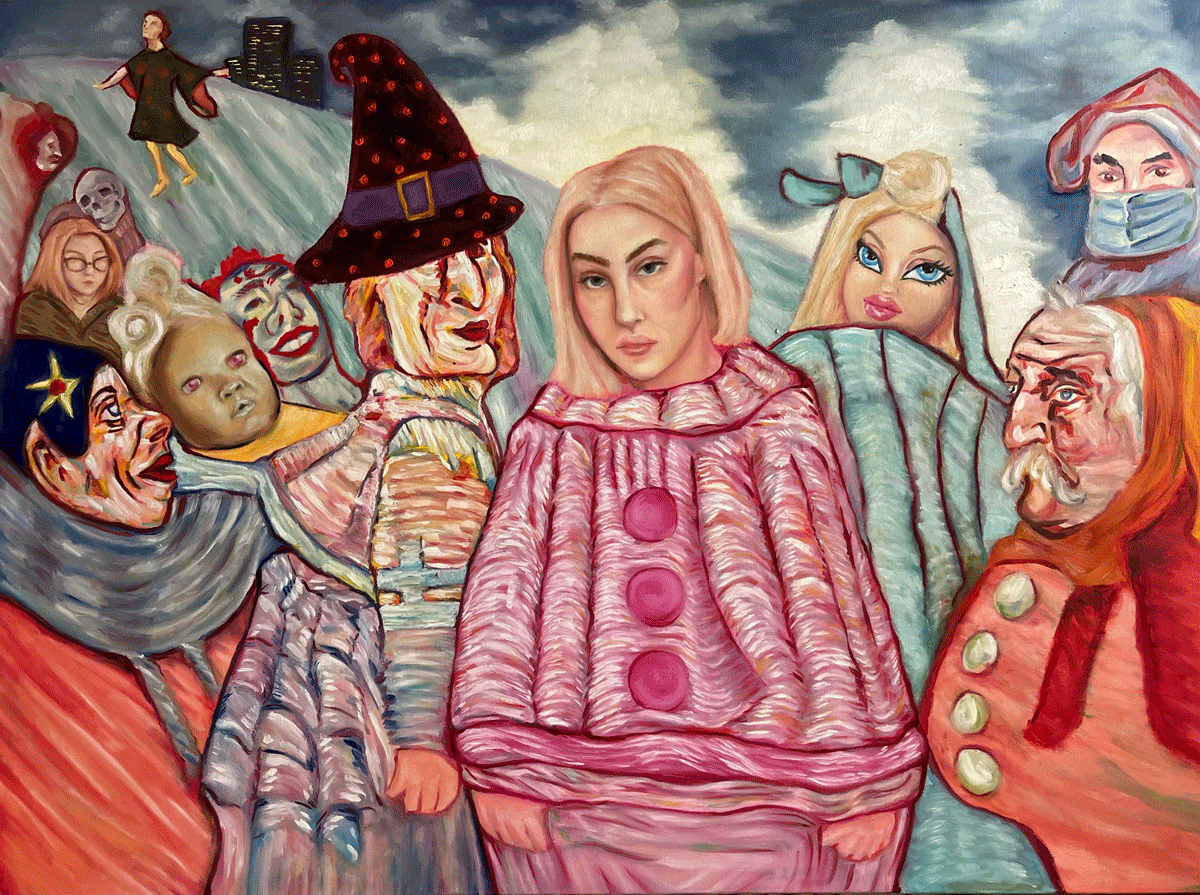

Artwork by Chloe Eick for the zine Cher.

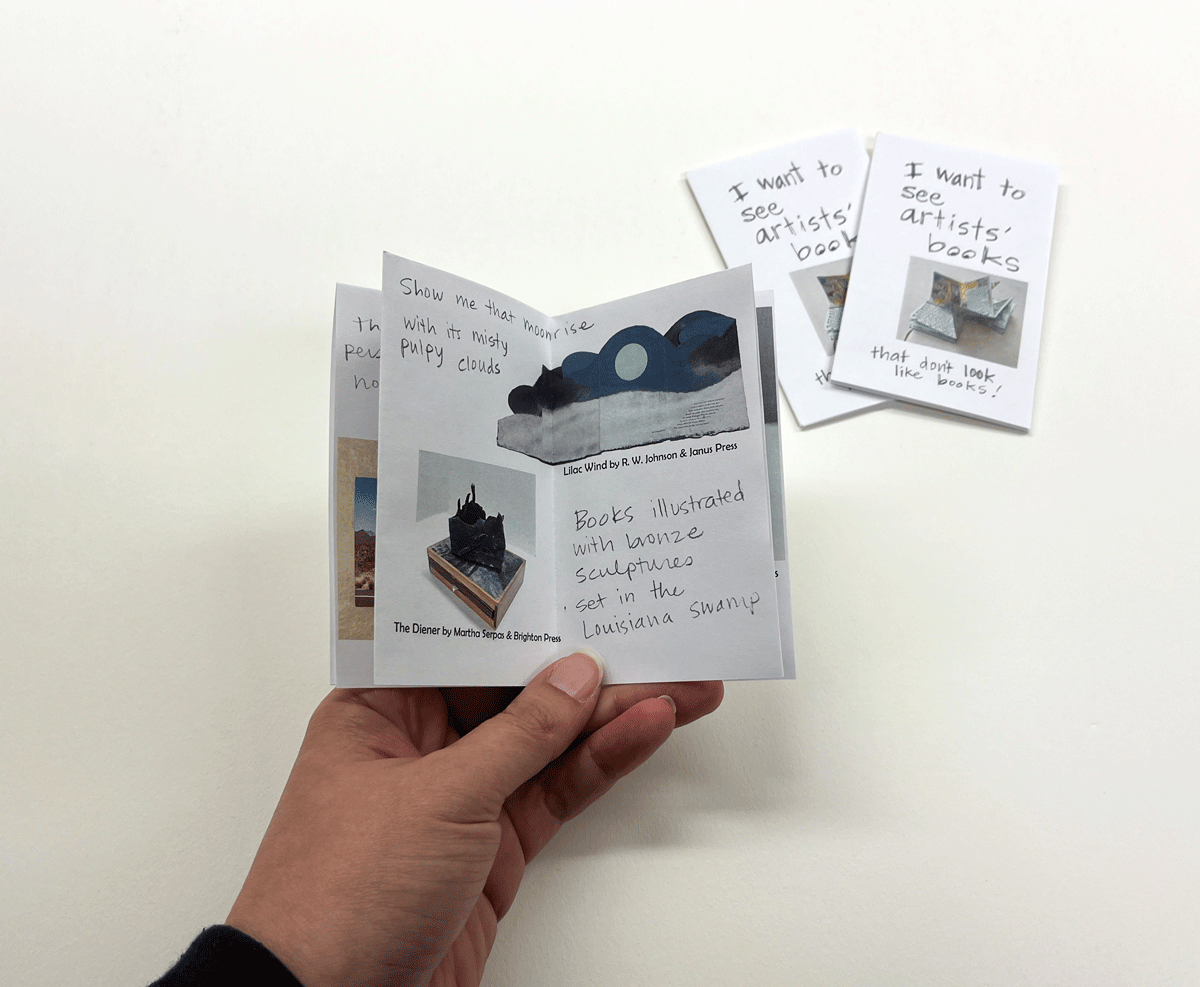

“I like that zines are easy to share,” said Caroline Ziegler, conservation coordinator at Hill Memorial Library. Ziegler works closely with the artists’ book collection at the library. Artists’ books, sometimes also called book arts, are art pieces that incorporate some elements of books. Some are artistically printed and bound; some have traditional book formats and contain original art; some use unusual folding techniques and sculptural elements. Ziegler started making zines to promote the artists’ books, combining two sides of the spectrum of printing possibilities.

“Zines can go where artists’ books can’t,” Ziegler explained. Her first library-specific zine complemented an exhibition of artists’ books at Hill Memorial in 2020. The same month, the College Book Art Association was held in New Orleans. “I made this little zine called Welcome to Hill Memorial Library. It was basically, ‘Hey, come to Baton Rouge and see our book arts show.’ I’m pretty sure no one at the conference took me up on that offer, but we were also able to share the zine with students around campus and that worked out well.”

Most recently, Ziegler created a zine to highlight an online library guide. I Want to See Artists’ Books That Don’t Look Like Books features artists’ books from Hill Memorial Library that use sculptural and other elements that deviate from common book structures. “I wanted to make a visual guide to the artists’ books in the collection, a guide that artists on campus could use to find the items and use them for inspiration for future work,” Ziegler said. “And I wanted to create the zine because I didn’t want people who love physical items to miss out because they don’t spend time on library websites.” So, Ziegler made a zine to promote the online guide promoting the items in the collection. “Maybe someone might not go to the library website, but they might pick up a zine.”

In fact, lots of people have picked up that zine. Ziegler reports hearing from students across campus that they found this zine and have used it to seek out both artists’ books at Hill Memorial as well as additional zines in the community. In fact, it was I Want to See Artists’ Books That Don’t Look Like Books that Adrienne Lewis found at LSU Libraries just a few weeks after arriving in Baton Rouge. Ziegler’s zine led Lewis to visit the zine library and meet a community of like-minded people in Baton Rouge.

Zines have a way of working like that. They fill gaps between different channels of communication. They lead readers to online sources, library items, and even whole communities. They create bridges between people and offer shared platforms for artistic expression and experimentation. They can sit on shelves for years before being discovered by new readers, which gives them staying power rarely seen in a digital or social media landscape. They require more attention and effort than social media posts, and less than traditionally published books or journal articles—which makes them perfectly positioned for those who know how to use them.

Sophie Ziegler (they/them) is a librarian, archivist, oral historian, and educator based in Baton Rouge. They are a co-founder of Mapping Trans Joy, director of the Solidarity History Initiative, and lead organizer of Screaming into the Future, a zine library and studio space in Baton Rouge.