Magazine

Echoes of Inner Conflict

Revisiting the complex history and populace sentiment of Robert Penn Warren's 1956 Segregation. The third in a series funded by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative.

Published: September 1, 2016

Last Updated: May 2, 2019

Library of Congress.

A Pulitzer-winning poet and novelist, Robert Penn Warren turned to journalism in 1956, interviewing the young and old, black and white about their views on segregation.

Every few minutes a disruption broke out and each time Trump halted his speech. He pointed at the protestors, ridiculing them, while plainclothes security guards mobilized. The protestors lifted their middle fingers and held up signs: “Black Lives Matter!” “KKK 4 Trump,” and “The Only Walls We Build Are Levees.” Trump supporters yelled: “All Lives Matter!” “Get out, immigrant!” “Go back to the unemployment line!” The interruptions electrified the crowd, the background roar spiking into a crescendo of euphoric hate. An older man beside me (suspenders, bushy mustache, a file of pens clipped to his breast pocket) told his wife: “They’re lucky I wasn’t allowed to bring my .40 in here. I would have unloaded my clip straight into those—.” It was an exercise in catharsis. The protestors and the supporters both were giddy from their exertions.

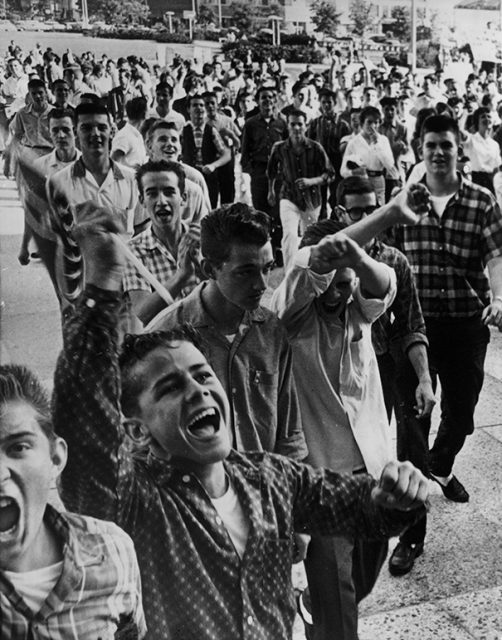

On November 16, 1960, a crowd of white teenagers marched on New Orleans’ City Hall to protest the integration of the city’s public schools. Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University

Yet as vehement or crass as their speech could be, they spoke in euphemisms. Nobody said, for instance, “We have to keep the white race intact.” Nobody said, “the red-neck…got to have something to give him pride. Just to be better than something.” Nobody said, “I have a deep contempt for the Negro race as it exists here. It is not so much a matter of ability as of character.” But such statements were made openly to Robert Penn Warren in 1956 when, on assignment for Life, he traveled through the South to chronicle the reaction to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. Warren’s report — published in book form as Segregation: The Inner Conflict in the South — remains startling today, not because of the attitudes themselves, but because of the candor with which they are expressed. In this aspect, 1956 was a more liberated time than 2016. Segregation was a mainstream political issue and Americans on either side of the debate, perhaps for the last time in the nation’s history, felt free to speak openly about race.

Warren found himself in much the same position as the nation in 1956, conflicted and uncertain. Born in the small town of Guthrie, Kentucky, in 1905, Warren grew up on a tobacco farm paces from the Tennessee state line. Both his grandfathers fought for the Confederacy at Shiloh. His first published essay was “The Briar Patch,” a tepid endorsement of segregation and the Southern way of life. “In the past the Southern negro has always been a creature of the small town and farm,” Warren wrote. “That is where he still chiefly belongs, by temperament and capacity.”

Race did not figure prominently in his early novels, an omission that is particularly notable in All the King’s Men (1946), which won Warren the Pulitzer Prize and elevated him to national celebrity. The novel’s populist governor, Willie Stark, was modeled loosely on Louisiana Gov. Huey P. Long, who was assassinated in 1935: Warren had moved to the state in 1934 to teach at Louisiana State University and remained for eight years. Though Long’s popular appeal derived in part from his paternalistic attitudes on race, progressive for the Jim Crow South, Willie Stark is silent on the subject. So, with one exception, is Warren. When black characters do appear in the novel, they are reduced to the dingiest of clichés. In the novel’s famous opening paragraph, Warren’s narrator Jack Burden describes speeding through the country and losing control of the automobile:

Then a nigger chopping cotton a mile away, he’ll look up and see the little column of black smoke standing up above the vitriolic, arsenical green of the cotton rows, and up against the violent, metallic, throbbing blue of the sky, and he’ll say, “Lord Gawd, hit’s a-nudder one done done hit!”

Warren touches directly on the subject only in the historical interlude about Cass Mastern, a man whom Burden believes (incorrectly, it turns out) to be his great uncle. In the story within the story, Mastern has a crisis of conscience, frees his slaves and becomes an abolitionist, only to die of gangrene while fighting for the Confederacy. Mastern’s bravery seems a rebuke to Burden’s cowardice, but Warren drops the subject of race as abruptly as he does Mastern.

After 1950, when Warren began teaching at Yale, his writing seemed to reflect a sudden grim realization that American history was, from its beating heart to the farthest reaches of its vascular system, the story of slavery and its legacy. Brother to Dragons (1953) is a novel in verse about the murder and dismemberment of a slave by two nephews of Thomas Jefferson; Band of Angels (1955) is a histrionic saga narrated by the daughter of a slave who seeks legal and spiritual freedom. But in Segregation Warren turns his attention to the present day, abandoning romantic lyricism and metaphysical turbidity for an elegant, journalistic style. He travels through the “sad and baleful beauty of the Delta,” to Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana. He speaks with a farmer “under the naked light of a flyspecked 200-watt bulb hanging from the shed roof” and with a segregationist official in “a fringe subdivision, in a small living room with red velvet drapes.” He interviews taxi drivers, barbers, lawyers, college students, NAACP officers, housewives, state government employees, priests, newspapermen, owners of small businesses. They are young and old, rich and poor, black and white. He poses plain questions and receives plain responses.

Children in Louisville, Ky., emerge from school after the first day of integrated classes in September 1955. Photo by James Burke/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Warren italicizes the questions: What are the white man’s reasons for segregation? What does the Negro want? Is there any difference between what the Negro feels at the exclusions of segregation, and what a white man feels at the exclusions which he, any man, must always face at some point? What’s coming?

His Tennessee accent wins a warm greeting from most of his interlocutors. But not all. When a former Klan official, interviewed in his Tennessee living room, begins to stumble over his justifications for white supremacy, his wife interrupts.

“Excuse me,” she suddenly says, but addressing me, not the husband, “excuse me, but didn’t you say you were born down here, used to live right near here?”

I say yes.

She takes a step forward, coming out of the shadow. “Yes,” she says, “yes,” leaning at me in vindictive triumph, “but you never said where you’re living now!”

But this suspicion of the outsider, the northerner (or the corrupted southerner) and the press never inhibits speech. Too much is at stake. Despite “the Supreme Court decision,” as it is invariably referred to, Warren’s subjects consider segregation an open question. They are at pains to explain themselves. Many of the segregationists seem to believe that their side can still prevail, if only their arguments are more clearly understood.

Their arguments are achingly familiar to Warren, however, as they would have been to his readers in 1956. Several are put bluntly by a propagandistic handbill handed to Warren by a blond lawyer for a segregation group: “Segregation is the law of God, not man…these people will overwhelm the white race and destroy all progress, religion, invention, art, and return us to the jungle…Negro blood destroyed the civilization of Egypt, India, Phoenicia, Carthage, Greece, and it will destroy America!” More cautious advocates contend that it is a question not of race but of state’s rights; that a black underclass is needed to restore “pride” to poor whites; that black advancement will threaten white financial stability. “If we’re logical, we ought to deny any good facilities to them,” says one wavering young Mississippian. “Now I’m a segregationist, but I can’t be that logical.”

Warren receives direct responses but the answers to the big questions remain evasive. Few speakers address, for instance, the source of their profound fear. Warren calls this “the fear of abstraction”: “the instinctive fear, on the part of black or white, that the massiveness of experience, the concreteness of life, will be violated.” A black scholar he interviews puts it more directly:

A lot of people down here just don’t like change. It’s not merely desegregation they’re against so much, it’s just the fact of any change. They feel some emotional tie to the way things are. A change is disorienting, especially if you’re pretty disoriented already.

This is the crucial point for Warren. New laws do not produce the disorientation. It arises when one’s morals come into conflict with one’s practices. The book’s subtitle, “The Inner Conflict in the South,” refers not merely to the conflict within the region, but the conflict within each southerner. (A similar inner conflict existed, and exists still, in the north, which has its own cognitive strategies for ignoring racial inequity.) As a southern college student tells Warren, “people don’t like to feel like they’re spitting on their grandfather’s grave. They feel some connection they don’t want to break. Something would bother them if they broke it.” And yet: “sometimes something bothers them if they don’t break it.”

Segregation was a mainstream political issue and Americans on either side of the debate, perhaps for the last time in the nation’s history, felt free to speak openly about race.

It is this inner tension, more than any policy argument, that Warren wishes to expose to sunlight. “A division between man and man is not as important in the long run,” he writes, “as the division within the individual man.” Such violent self-division distorts one’s sense of identity. It even distorts one’s grasp of reality. In making this point Warren echoes James Baldwin, who wrote forcefully of the ways in which racism destroys those who practice it. “At the root of the American Negro problem,” Baldwin wrote in “Stranger in the Village” (1953), “is the necessity of the American white man to find a way of living with the Negro in order to be able to live with himself.” So it is with Warren. The dilemma is personal for him. Though he never breaks his journalistic character, his final interview is with himself.

“I don’t think the problem is to learn to live with the Negro,” says Warren.

Q: What is it then?

A: It is to learn to live with ourselves.

Q: What do you mean?

A: I don’t think you can live with yourself when you

are humiliating the man next to you.

It is a form of terror, this inability to live with yourself. As the college student tells Warren, “Everybody is scairt.”

Segregation went largely unreviewed in the South; several northern critics were angered by Warren’s prediction that integration would take time. It would only come, he writes, “When enough people…cannot live with themselves any more.” A state official foresees “a creeping process” toward integration, punctuated by court actions (“but don’t let court actions fool you”). A Methodist minister predicts it will take 25 or 30 years. A grade-school superintendent guesses a half-century.

Sixty years have passed. There have been countless court actions but only modest declines in residential segregation. Some of the nation’s most integrated cities are in the South — Atlanta, Austin, Dallas — but even there segregation levels remain high. Grotesque racial imbalances persist in the criminal justice, public housing, health care and education systems. “Brown at 60,” a recent national study by the UCLA Project on Civil Rights, the first in decades, found that while the South has the least segregated public schools in the nation, they are no more integrated today than they were in 1967.

Police drive back an angry crowd gathered at the offices of the New Orleans school board on November 16, 1960. Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center, Tulane University

The most dramatic transformation has been rhetorical. Too many Americans today indulge in what Baldwin, writing about self-satisfied northerners in the 1950s, called “an extremely dangerous luxury.” We seem to believe, because nobody today dares to speak in public like Warren’s subjects, that the old problems are gone — that what segregation exists is by choice or habit. The shadow play has infected both sides of the conversation. Even civil rights activists use cautious terms like “micro-aggression” to describe acts of casual racism, or say “Black lives matter” when they mean to condemn the race-driven murders of black men by police officers.

In his own way Trump has contributed to the unmasking of this rhetorical slipperiness. He has done so by pushing such double-talk to its breaking point. “I don’t have a racist bone in my body,” he said, after coming under attack for his plan to wall off the southern border. “I’m just exposing things that everybody knows is happening, but nobody wants to talk about.” He goes far enough to attract the enthusiastic support of white supremacists, while making certain to preserve plausible deniability. He did not disavow David Duke’s endorsement at first because he was wearing a “very bad earpiece” and couldn’t hear the interviewer’s question; the Star of David is a sheriff’s badge; he does not know whether Obama is a Muslim (as two thirds of Trump’s supporters believe); when he uses the slogan “America First,” he intends no echo of the eponymous nationalistic, Nazi-sympathizing movement led by William Randolph Hearst in the 1930s. He is beloved for expressing opinions that other politicians are too afraid to say in public. For many supporters he is helping to erase the division between what they think and what they are allowed to say. The relief one observes at a Trump rally or, for that matter, at a Black Lives Matter rally, derives from the satisfaction of expressing for the first time in public, at full voice, one’s private convictions. Euphemisms are still employed, though they are threadbare and rapidly disintegrating. After 60 years the nation’s inner division may be as rigid as ever but tentatively, for worse and for better, we are beginning again to speak honestly.

—–

Nathaniel Rich is the author, most recently, of Odds Against Tomorrow. He lives in New Orleans, Louisiana.

This article was made possible by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a program to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Prizes in 2016. Announced by the Pulitzer Prize Board, the Campfires Initiative aims to ignite broad engagement with the journalistic, literary, and artistic values the Prizes represent. The board partnered with the Federation of State Humanities Councils on the initiative and awarded more than $1.5 million to forty-six state humanities councils.

This article was made possible by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a program to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Prizes in 2016. Announced by the Pulitzer Prize Board, the Campfires Initiative aims to ignite broad engagement with the journalistic, literary, and artistic values the Prizes represent. The board partnered with the Federation of State Humanities Councils on the initiative and awarded more than $1.5 million to forty-six state humanities councils.