Emma Wilson Emery

Louisiana’s first poet laureate was female—and vehemently anti-war

Published: June 1, 2020

Last Updated: September 1, 2020

Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University

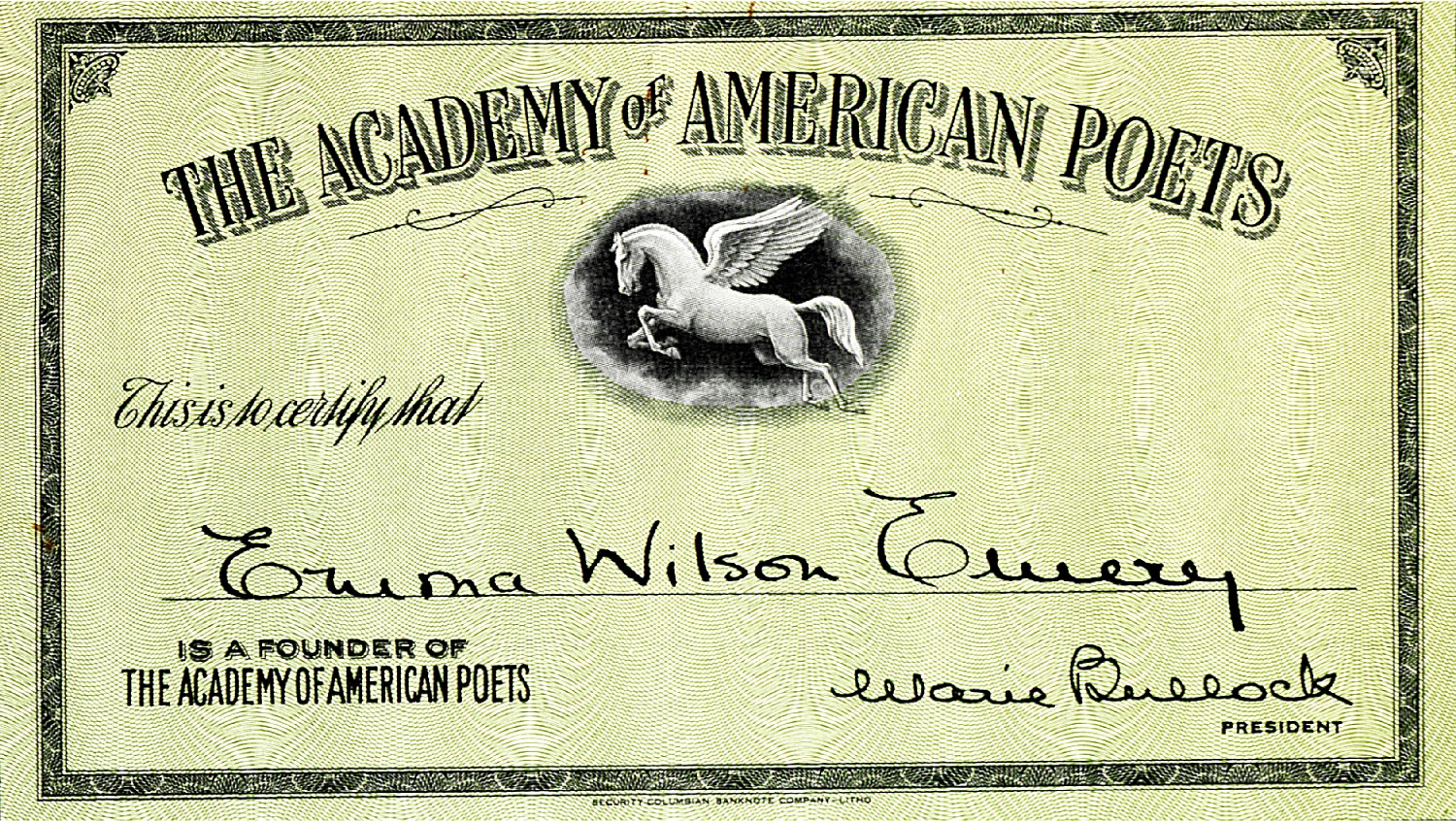

Emery’s membership card in the Academy of American Poets.

This year, I’ve endeavored to read more Louisiana poets, beginning with our lineage of laureates. Louisiana’s current poet laureate, John Warner Smith, a Morgan City native, Southern University English professor, and author of four collections, began serving his two-year term on August 14, 2019, becoming the fourteenth writer, and first African-American man, to hold the post.

The state’s poet laureate position dates back to 1942, when Governor Sam H. Jones named Emma Wilson Emery of Shreveport to serve. Though a longtime North Louisiana resident, Emery was born in East Texas, in 1885. Her parents hailed from Spurger, a pine timber town founded by her great-grandfather near the Neches River. Her father’s family didn’t cotton that his beloved’s bloodline ran with Cherokee stock, so David Henry Wilson and Eula Gilmore eloped in exile. Infant Emma was born in a covered wagon, she later liked to point out, “moving across the plains of Texas.”

The new family settled in Plank, a recently established sawmill town no doubt named for the product that filled its lumber yards. A dozen years later, with the East Texas timberlands exhausted, the Wilsons rerooted themselves to North Louisiana, eighteen miles deep in a virgin longleaf pine forest outside the town of Boyce. After a spell back in Texas, typesetting for the Nacogdoches Plaindealer, Emma—who went by Emm—resettled in Shreveport, where she graduated from nursing school and married one of her patients, Robert Emery. She founded the city’s Red Cross chapter and supervised nurses there during the First World War.

The most popular of all her poems was “Lovely Louisiana,” which was beloved enough to be printed in state textbooks, distributed on pocket-sized cards to homesick military men and women during World War II, and nearly, in 1955, voted the official state song.

Emery’s papers, archived in Louisiana State University’s Special Collections, give no hint as to when she first started writing poetry. Her memoirs, Aunt Puss & Others: Old Days in the Piney Woods (1969), mention participating in a school poetry recital at the age of eight, when, overcome with excitement while delivering Constance Fenimore Woolson’s Civil War epic “Kentucky Belle,” her undergarments fell around her ankles. (She finished the poem, only to trip over her drawers.)

Her debut collection, Velvet Shadow, published by Parnassus Press of New York in 1934, established a blueprint for her four decade-long career. Most of these early poems employ a conventional alternative rhyme scheme, as in “Tornado”: “Rain, rain, incessant rain; / Rivers beneath my feet! / Ageless pines moaning with pain— / Terror forcing retreat! / Muffled sobs—a distant wail, / Man’s life flung to the shattering gale!” There are romantic poems (“Strange Is the Way of Love”) and nature poems (“To a Pine Tree”), with many containing Christian over- and undercurrents, like this first stanza from “Sorrow in the House”: “To every life there comes / One day the quiet hour, / When all the tinsel / And the gilt is laid away; / When heavy on the heart is prest / The fragrance of a flower, / Then there is nothing one can do / But pray.” Only occasionally, Emery allowed her verse a touch of levity, as in the short and silly “The Poet’s Apology to a Sock”:

Today the socks in heaping piles

Were begging to be mended.

My intentions were the best—

To darn them I intended,

I said to them, “I’ll mend you soon”—

I said it quite aloud,

But could I thread a needle

While riding on a cloud?

But Velvet Shadow’s weightiest compositions, in content if not form, take war as their subject. Not two decades removed from one world war, with the threat of a sequel on the horizon, Emery was above all else a peacenik, and antiwar poetry would become her métier throughout the next, cruel decade.

“Let not another lad go forth,” she writes in a poem of the same name, “With the light of youth in his eye; / A smile on his lips, a gun in his hand; / A lad too young to die.” It’s a message that threads throughout the collection, in poems with titles such as “A Plea For Brotherhood” and “Guns At Dawn,” with its final lines of melancholic supplication: “Out of the holocaust I try / To find a reason to justify / The spilling of warm, young blood— / Dear God, is there an answer? Why?”

Around the same time as Velvet Shadow’s publication, Emery relocated to Chicago (her husband passed away in 1923). There, she produced and wrote for CBS Radio’s Poetic Melodies program. Her second collection, Bleeding Heart and Rue (1937), a compilation of her radio pieces, echoed the simple structure and themes of her first, with a small handful of surreal outliers perhaps influenced by the in-vogue modernists, a trend she purported to detest. “I don’t think much at all of modern poetry,” she’d tell a reporter years later. “I see no beauty in it.” But verses such as “Within an April Cloud” reveal a paradigm shift, however subtle:

For dancing girls from Old Madrid

Trip by with rhythmic grace;

A snow-white polar bear climbs down

To claim the dancers’ place.

Now watch the funny little man

From Lord knows where, bob up,

A blossom pinned upon his nose

And in his hand a cup;

He seems to be quite joyous there

While drinking to his fill—

The blossom’s gone—now he is too!

The cup is floating still

Beneath a budding cherry tree

That comes from far away.

Emery’s third collection, Songs of Victory (1944), was a return to form. Dedicated to “the men and women in our armed forces everywhere,” this slim volume contains thirty-five wartime peace poems, some new, some reprinted from her earlier compilations, many read and broadcast from NBC and CBS radio studios in Chicago to troops toiling in the Pacific Theater. The caustic, cynical ““Armistice””—note the ironic quotes—aptly showcases Emery’s state of mind:

Twenty-six years ago today,

“Armistice,” they said.

Yet comes another far-flung cry

As wounded heroes fall and die

In new-made trenches over there.

The world too soon forgot its prayer

Of gratitude, its pledge to peace,

Its grief-torn view that “War shall cease.”

Back in Shreveport, Emery had by then received the call naming her Louisiana’s first poet laureate. “I literally fell backward,” she remembered, thinking, “This must be a joke.” But there was doubtfully anyone as deserving as Emm Emery. Several of her scrapbooks, held in Louisiana State University’s archives, attest that her poetry was more or less omnipresent in local and national publications during her lifetime. The most popular of all her poems was “Lovely Louisiana,” which was beloved enough to be printed in state textbooks, distributed on pocket-sized cards to homesick military men and women during World War II, and nearly, in 1955, voted the official state song. The poem, which can readily be found online, is very much a product of its era—with imagery of “ghostly” cotton fields and “age old oaks” whispering “secrets evermore.”

Emery would hold the post of state poet laureate until her death in 1970. But fame is fleeting, especially for poets. A just published who’s-who compendium of poets past and present neglects to include any mention of Emery. So, I’ll let her have the last word. In this poem, titled “Requiem,” included in her first collection, and dedicated to her Cherokee great-great-grandfather, Chief Red Leaf, Emery offers a remembrance to all those souls, dearly remembered and regretfully forgotten, who have passed before us.

Where are the ways

Your swift feet knew

When the hills were yours

And the valleys too?

Where are the songs

You used to sing

By the river, the brook,

The crystal spring?

Your paths are lost

In the dust of years,

Your songs are hushed

In a mist of tears;

And I hear the wind

In the pines overhead

Whispering a requiem

For your dead.

Rien Fertel’s essays on early Louisiana literature appear in two recent edited collections, Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity and New Orleans: A Literary History.