A Streetcar Named Desire

In 1947 playwright Tennessee Williams premiered A Streetcar Named Desire, a critically acclaimed theatrical work that won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1948.

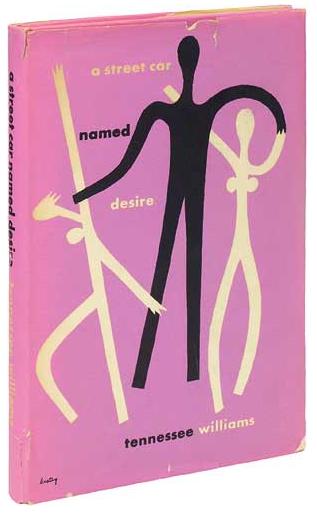

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A Street Car Named Desire. Williams, Tennessee (Author)

In 1947 playwright Tennessee Williams premiered A Streetcar Named Desire, a critically acclaimed theatrical work that won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1948. The play has come to symbolize the sultry and raffish ambience of New Orleans and is one of the most recognized literary works associated with the city. The title refers to a streetcar line that ran through working-class downtown neighborhoods from Canal to Desire streets.

Origins

In 1939 Williams wrote to his agent, Audrey Wood, “I have an idea for a new long play—rather, a character—in New Orleans—Irene. As you have observed, I have only one major theme for all my work which is the destructive impact of society on the sensitive, non-conformist individual. In this case it will be an extraordinarily gifted young woman artist who is forced into prostitution and finally the end described in the story.”

By 1947 “Irene” would become Blanche Dubois, and A Streetcar Named Desire would earn Williams his first Pulitzer Prize in 1948.

Streetcar stands in contrast with Williams’s highly successful The Glass Menagerie (1944), which he called his “memory play.” Menagerie has a dreamy, unmoored-from-time quality; Streetcar is gritty and real. Where Menagerie’s set used scrims and projections to slightly blur perception, Streetcar puts Stanley and Stella Kowalski’s grimy New Orleans apartment at 632 Elysian Fields Avenue center stage.

Williams summarized Streetcar’s plot for his agent in 1945: “At the moment it has four different titles, The Moth, The Poker Night, The Primary Colors, or Blanche’s Chair in The Moon. It is about two sisters, the remains of a fallen southern family. The younger, Stella, has accepted the situation, married beneath her socially, and moved to a southern city with her coarsely attractive, plebeian mate. But Blanche has remained at Belle-reve [French for “beautiful dream”], the home place in ruins, and struggles for five years to maintain the old order … Blanche, destitute, gives up the struggle and takes refuge with Stella in the southern city.”

Streetcar in its final version remained true to Williams’s original concept. He had planned to write the play during a long stay in Mexico, but in 1946 eventually returned to New Orleans—the city he called his “spiritual home” and where he had resided off and on since 1938. He rented an apartment at 632 St. Peter Street in the French Quarter. Its location—near St. Louis Cathedral and the Desire streetcar line—and its address were woven into the play.

A Tale of Passion and Betrayal

The play is presented in eleven scenes, with four main characters and a handful of supporting characters. In the first scene Blanche enters the rundown apartment of her sister and brother-in-law, Stella and Stanley Kowalski, after a short but exhausting trip from Laurel, Mississippi. The audience quickly learns that she had been in a short, tragic marriage and had nursed dying relatives at the Dubois family homestead, which has been lost to debt. As Blanche tells Stella, “How in hell do you think all that sickness and dying was paid for? Death is expensive.” In a moment of brutal honesty she says, “Where were you! In bed with your—Polack!” The audience also learns that Blanche lost her high school teaching position in Laurel when the town learned that she had been a frequent visitor to a dubious local hotel, which she jokingly calls “The Tarantula Arms.”

The Kowalskis live in a no-nonsense world; their one-bedroom apartment’s only interior door is to the bathroom. When Blanche’s steamer trunk arrives full of showy but tattered clothes, costume jewelry, and “summer furs,” it gives her an aura of faded glamour.

Stanley has no patience for Blanche’s artifice. Their frank conversation about property and Louisiana’s Civil Code underscores his practicality. Blanche admits that Belle Reve was “lost piece by piece” over the generations, until all that was left was “about twenty acres of ground, including a graveyard.” The audience soon learns that Stella is pregnant, adding urgency to the plot.

The next night, the ladies have dinner at Galatoire’s restaurant, leaving Stanley at home for his poker night. When they return the game is going full tilt, ending in a fight during which Stanley strikes Stella in a drunken rage. Stella retreats to the upstairs neighbors’ apartment, and soon Stanley appears at the bottom of the stairs, howling for Stella. Blanche is horrified as she watches them embrace. The following morning, still alarmed by Stella’s willingness to live with a man as brutish as Stanley, Blanche proclaims to her sister, “You’re married to a madman!” Stella defends her passionate love for Stanley and describes details of their wedding night, which prompts Blanche to reply, “What you are talking about is brutal desire—just—Desire!—the name of that rattle-trap streetcar that bangs through the Quarter, up one old narrow street and down another. …” Blanche further admonishes her sister: “He acts like an animal, has an animal’s habits! Eats like one, moves like one, talks like one! There’s even something—sub-human—something not quite to the stage of humanity yet! Yes, something—ape-like about him … Thousands and thousands of years have passed him right by, and there he is—Stanley Kowalski—survivor of the stone age!”

In the weeks that follow, Blanche goes on several dates with Stanley’s coworker Mitch, a quiet, polite fellow whom Blanche proclaims as “superior to the others.” As in The Glass Menagerie, where a “gentleman caller” seems the magical answer to several problems, Mitch appears to be Blanche’s salvation. One evening she tells him about her late husband, a closeted homosexual who killed himself while out with Blanche and the man who was likely his lover. The story actually seems to draw Mitch closer to Blanche; however, Stanley eventually tells Mitch about Blanche’s sordid life in Laurel.

Devastated and all the more desperate, Blanche continues to dream of escape. When Stella is in the hospital after having her baby, she and Stanley are alone in the apartment. Blanche tells Stanley that she will soon be leaving for a trip with the wealthy Shep Huntleigh of Dallas, a suitor from long ago. But her story quickly dissolves and she calls the telephone operator, asking for Western Union. She sputters, “Take down this message! In desperate, desperate circumstances! Help me! Caught in a trap.” Stanley confronts her and, as the scene ends, proclaims in a sexually aggressive manner, “We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning.”

The final scene is brisk and takes place “some weeks later.” Blanche is dressing and Stella is talking with her neighbor and landlady, Eunice. Mental health officials arrive to take Blanche to what the audience assumes will be the state mental hospital. Stanley and his friends are playing cards in the front room, a grim reminder of previous poker nights. Blanche is briefly traumatized, particularly when she sees Stanley, but the doctor is able to calm her and guide her out of the apartment while she voices one of the plays most memorable lines: “I have always depended upon the kindness of strangers.”

A Smash Hit and Movie Adaptation

Critical acclaim for the play was immediate, with particular praise for actress Jessica Tandy who was cast as Blanche. Brooks Atkinson in the New York Times wrote in his review, dated December 4, 1947, “This must be one of the most perfect marriages of acting and playwriting. For the acting and playwriting are perfectly blended in a limpid performance, and it is impossible to tell where Miss Tandy begins to give form and warmth to the mood Mr. Williams has created. … Like The Glass Menagerie, the new play is a quietly woven study of intangibles. But to this observer it shows deeper insight and represents a great step forward toward clarity. And it reveals Mr. Williams as a genuinely poetic playwright whose knowledge of people is honest and thorough and whose sympathy is profoundly human.”

In 1951 Williams teamed with Oscar Saul to adapt Streetcar into a screenplay. The Warner Brothers movie was directed by Elia Kazan and has since been declared “one of the greatest American movies of all time” by the American Film Institute. Marlon Brando (Stanley), Kim Hunter (Stella), and Karl Malden (Mitch), all members of the original Broadway cast, were contracted for the film. Vivien Leigh was selected as Blanche; she had performed the role on the London stage. The film was nominated for twelve Academy Awards in 1951, including Best Motion Picture, and garnered four Oscars: Actress in a Leading Role (Leigh), Actor in a Supporting Role (Malden), Actress in a Supporting Role (Hunter), and Art Direction.

Among the most popular events at the annual Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival held in New Orleans each spring is a “Stella” yelling contest in which contestants vie to imitate Stanley Kowalski’s impassioned bellow for his wife as portrayed in Streetcar’s notorious poker night scene.