The Awakening

This entry provides an overview and analysis of Kate Chopin's short novel "The Awakening."

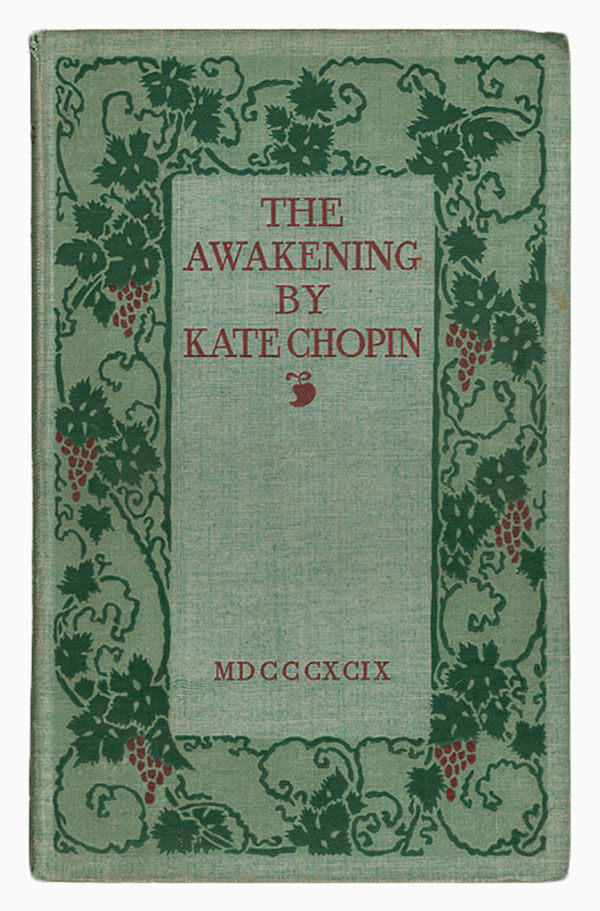

Courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries.

An image of the first edition of "The Awakening" by Kate Chopin, published in 1899.

Although Kate Chopin lived in St. Louis, Missouri, for most of her life, the few years that she spent in Louisiana profoundly influenced her writing career, which lasted from about 1888 to 1902. Her best-known work, The Awakening (1899), created a sensation in its day by depicting a woman whose dissatisfaction with her role in society leads her to seek a life independent of her husband and children. The short novel was nearly forgotten for more than fifty years until feminist scholars in the late twentieth century championed Chopin’s work as a courageous declaration of women’s sexual and spiritual yearnings.

The Awakening tells the story of 28-year-old Edna, a Kentuckian married to 40-year-old French Creole Léonce Pontellier, a New Orleans businessman. The novel opens as Edna and her two young sons are summering along the Gulf of Mexico at Grand Isle, in beachfront cottages owned by Madame Lebrun from New Orleans, where “exclusive visitors … enabled [Madame Lebrun] to maintain the easy and comfortable existence which appeared to be her birthright.” Léonce has arrived for the weekend, but by Sunday morning he seems distracted by the activity around him and heads off for an afternoon of gambling at the resort hotel. Edna spends the day with Robert, Madame Lebrun’s son, a 26-year-old unmarried merchant with vague plans of traveling to Mexico.

Surrounded entirely by French Creoles who know each other well, Edna is mildly shocked yet titillated by the disarming candor of conversation among her summertime friends. Eventually, influenced by such company and by the island’s serenity, “she [begins] to loosen a little the mantle of reserve that had always enveloped her.” Edna struggles to express that she feels constrained by her life in New Orleans. She learns to swim, moving farther from shore as the summer passes, an outward sign of her desire for more freedom.

Edna’s inner life is rendered honestly—in all its pettiness. She loves her children “in an uneven, impulsive way. She would sometimes gather them passionately to her heart; she would sometimes forget them. … In short, Mrs. Pontellier was not a mother-woman.” Adèle Ratignolle, another Grand Isle neighbor, is just such a “mother-woman,” an amalgam of beauty, fecundity, and devotion to family whom Edna thinks of as a “sensuous Madonna.” The contrast between the two women is further underlined when they debate about the self-sacrifice required of a mother, and Edna insists, “I would give up the unessential; I would give my money, I would give my life for my children; but I wouldn’t give myself.”

By summer’s end, Edna is gripped by a feeling she recognizes as “the symptoms of infatuation which she had felt incipiently as a child.” Robert Lebrun has finally decided to move to Mexico, and Edna feels her “whole existence dulled” in his absence. When she returns to New Orleans to her comfortable, well-appointed home on Esplanade Avenue, she cannot settle back into her expected routine. She goes out on the afternoons she is expected to receive visitors at home; Léonce is upset, but it comes to naught. Edna eventually abandons her receiving days at home altogether.

Edna instead spends more time with “artistic” friends from Grand Isle and continues her sketching and painting, although her devotion to art could best be called “dabbling.” She finds inspiration in the example of one of her Grand Isle acquaintances, Mademoiselle Reisz, a mature, unmarried woman who has devoted her life to developing her artistry on the piano. While Edna can confide in Mademoiselle Reisz about her feelings for Robert, the musician’s off-putting personality prevents any real friendship between the women. However, Edna’s visits to Mademoiselle Reisz move her to create her own life, separate from her husband and sons, while remaining in New Orleans.

When Léonce takes the children to Grand Isle on his own, Edna stays behind, delighted to have the house to herself. Through her circle of friends she meets Alcée Arobin; after several outings, they begin an affair. Chopin writes, “It was the first kiss of her life to which her nature had really responded. It was a flaming torch that kindled desire.” Perhaps most surprising to a reader of 1899 was Edna’s realization that she felt “neither shame nor remorse.”

Edna revels in her freedom, even taking up residence in a small cottage around the corner from her main house. Léonce, always concerned with appearances, creates a cover story that he and Edna will soon be taking a long European trip. Alcée remains devoted to Edna, but then Robert returns from Mexico and acknowledges that he had, in fact, been in love with Edna the previous summer. In the novel’s final New Orleans scene, she reads his brief note: “I love you. Good-by—because I love you.” Edna grows faint when she reads it.

In the final chapter Edna returns by herself to Grand Isle, and she casually tells her hosts that she will take a swim before dinner. Alone on the shore, Edna removes her bathing suit and “for the first time in her life she [stands] naked in the open air” before walking into the Gulf. Feeling the water’s “soft, close embrace,” she swims steadily out to sea until her strength fades and childhood memories surround her. Readers continue to debate whether Edna’s implied suicide represents victory or defeat in her struggle for independence.

Throughout The Awakening, Edna’s materially generous but socially persnickety husband allows her a good deal of personal freedom; nevertheless, she chafes under his relatively light demands. And there is, of course, her adultery—Edna both cherishes and coyly flaunts the romance. In some ways, the most shocking aspect of her affair is that it is not an end in itself, but rather an experiment—a step on the way to self-knowledge, “to realize her position in the universe as a human being.” The fact that Edna can objectify men as sexual conquests without feeling guilt makes her deliciously subversive, especially in late nineteenth-century Creole society.

Critical reception of The Awakening was mixed, usually acknowledging Chopin’s artistry while denouncing her subject. The St. Louis Globe Democrat’s review declared, “It is not a healthy book; if it points any particular moral or teaches any lesson, the fact is not apparent.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch was somewhat more positive, noting, “It is sad and mad and bad, but it is all consummate art. The theme is difficult, but it is handled with a cunning craft. The work is more than unusual. It is unique.”

The New York Times included the novel in its list of “100 Books for Summer” under the heading “A Group of Female Novelists,” although the editor is perhaps more evasive than helpful: “Would it have been better had Mrs. Kate Chopin’s heroine slept on forever and never had an awakening? … The author has a clever way of managing a difficult subject. … Such is the cleverness in the handling of the story that you feel pity for the most unfortunate of her sex.” Reviewers in the Chicago Times-Herald, The Nation, and Literature stated more definitely their disapproval of Edna’s morals. Critics and the public found the frank discussion of Edna’s desire for men other than her husband shocking and her rejection of motherhood unforgivable.

Chopin replied directly to her critics in the July 1899 Book News: “Having a group of people at my disposal, I thought it might be entertaining (to myself) to throw them together and see what would happen. I never dreamed of Mrs. Pontellier making such a mess of things and working out her own damnation as she did. If I had had the slightest intimation of such a thing, I would have excluded her from the company. But when I found out what she was up to, the play was half over and it was then too late.”

Chopin’s bantering public response hid the depth of her feeling; during a 1949 interview, Chopin’s son Felix said the criticism of her novel “hurt her deeply. … She was brokenhearted at the reaction to the book.” After suffering biting reviews nationally and social ostracism locally, Chopin wrote only a handful of short stories after The Awakening, all with more typical heroines who expressed conventional sentiments.