Bounce

With a steadfast regional following and hyperlocal lyrics in its earliest days, bounce music’s upbeat, danceable, participatory style now attracts an international audience.

Amistad Research Center

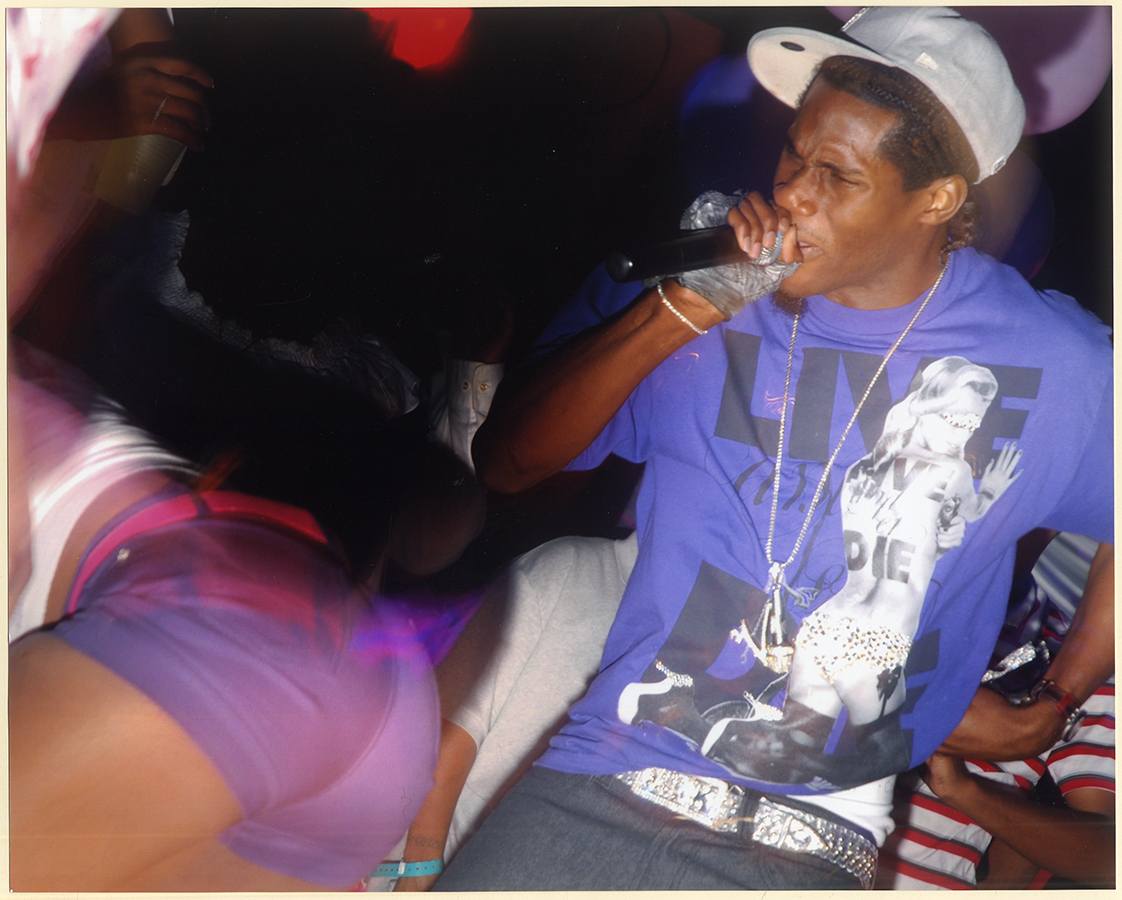

Vockah Redu performing with dancer, 2009. Aubrey Edwards, photographer.

Bounce music is a rap subgenre that emerged in the early 1990s in New Orleans. In its earliest days bounce was characterized by hyperlocal lyrical references, such as those included in the Showboys’ 1986 song “Drag Rap” (also referred to as “Triggerman” or “Triggaman” in the context of New Orleans bounce) and Cameron Paul’s “Brown Beats,” plus an upbeat, danceable, participatory style that encouraged audience call and response. Although New Orleans hip-hop artists who went on to national celebrity—like Juvenile and Mia X—recorded bounce songs early in their careers, the style itself remained steadfastly regional until the early 2000s, when bounce rapper Big Freedia began to attract a crossover international audience.

Beginnings and Hallmarks

In 1991 DJ Irv Phillips and MC T. Tucker released a cassette recording of one of the duo’s live performances at the Ghost Town Lounge in New Orleans’s 17th Ward neighborhood of Hollygrove. Known as the “red tape,” the song “Where Dey At” uses the distinctive “Drag Rap” 808 drum machine loop and arpeggio of bells mimicking the theme song to “Dragnet” and is widely considered the first bounce release. (Out of an increasing amount of locally produced rap in the 1980s and 1990s that referenced New Orleans, a 1989 single by MC Gregory D and DJ Mannie Fresh, “Buck Jump Time [Project Rapp]” is thought of in particular as a proto-bounce track because of its lyrics, which include a hyper-specific litany of references to New Orleans-area schools, neighborhoods, and public housing developments and would also become a hallmark of the sound.) Isaac Bolden, a New Orleans music-business impresario who had worked as a talent scout, producer, and independent record label owner since the 1960s, took note of the emerging club sound and later that year, recorded a more polished take at Allen Toussaint’s Sea-Saint Studios with another up-and-coming bounce rapper, DJ Jimi, and producers DJ Mellow Fellow and Dion “Devious D” Norman. That track was released as “Where They At” on the 1992 album It’s Jimi, which included the first credited appearance by the rapper Juvenile, then 17 years old.

Like brass band music—which was sampled often enough in early bounce music to be notable, stamping the sound even more decisively New Orleanian—bounce music was often performed and enjoyed in live settings. (Mardi Gras Indian chants and melodies, such as “Iko Iko” and “Let’s Go Get ‘Em,” were also borrowed for songs by rappers like K.C. Redd and Ricky B.) These ranged from nightclubs like Ghost Town, DJ Jimi’s home base Newton’s on Dryades Street in Uptown and Club Rumours on St. Claude Avenue to block parties in the semi-enclosed courtyards of the high-rise projects that were a common form of public housing architecture in New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina. Bounce evolved very much as dance music in these spaces, which were also arguably the birthplace of the now widely known hip-popping move known as twerking.

A slew of small, local independent labels also sprung up to record the music. The most notable were Mobo Records (home to Ricky B, whose classic 1994 songs “Shake It Fo Ya Hood” and “Yall Holla” were reissued in 2013 by Sinking City Records) and Take Fo’ Records. Larger local hip-hop labels like Cash Money, No Limit, and Big Boy—a label run by producer Leroy “Precise” Edwards, which was also Mystikal’s first recording home—released select bounce tracks early on, including the beloved “Pump the Party” by the R&B-inflected bounce duo Partners N Crime. Mia X, the crafty, complex lyricist who would become a flagship star of Master P’s No Limit Records, made her debut on the independent Lamina Label with “Da Payback,” a feminist answer song that responded to sexist tropes in the genre. Bounce rappers Ms Tee, Magnolia Shorty, and “gangsta bounce” group U.N.L.V. all recorded for Cash Money in the early 1990s before the label inked a landmark deal with Universal Music that turned it into a global powerhouse by the turn of the millennium. Cash Money house producer Mannie Fresh also worked separately, early on, with bounce rapper Cheeky Blakk, credited for introducing the word “twerk” into the lexicon with her 1994 song “Twerk Something” (spelled “Terk” on the original 1994 cassette release Gots 2 Be Cheeky). The “Cheeky Blakk beat,” with its distinct eighth-note hand claps, is another frequently used hallmark of early bounce music.

Growth

Take Fo’ Records, founded in 1992, was a label that has specialized in bounce since its inception. Their stable of artists included girl duo Da’ Sha Ra’; DJ Jubilee, a New Orleans Recreation Department sports coach and special-education teacher; and later Katey Red, the first openly gay rapper in New Orleans. The label made news in 2003 for suing Juvenile over similarities between DJ Jubilee’s 1997 Take Fo’ release “Back That Ass Up” and Juvenile’s megahit from later the same year, “Back That Azz Up.”

Public-access television in New Orleans was key to promoting and documenting bounce music. Take Fo’ Records aired a talk show titled “Positive Black Talk” to promote its artists on NOA-TV. Producers John and Glenda “Goldie” Robert and Chris Roberts (no relation) each produced MTV-style public-access television shows, titled “It’s All Good in the Hood” and “Phat Phat N All That,” respectively throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Coverage and airplay for the new sound were slim at the time. Karen Cortello, a programming director for local rap station Q93.3 FM wrote a hip-hop column in Offbeat magazine that also covered bounce music, and Times-Picayune music reporter Scott Aiges published two articles about bounce in 1991. Loren Phillips, a record store staffer in New Orleans and sister to DJ Irv of “Where Dey At” fame, also briefly published Da R.U.D.E., a magazine covering local hip-hop and bounce music.

Hurricane Katrina and Beyond

Like Mardi Gras Indians, brass-band musicians, and Social Aid and Pleasure Club members, the creators of bounce—as producers of organic, hyperlocal, largely live, and relatively unmonetized arts rooted in the Black community—were significantly more likely to be displaced following Hurricane Katrina, with the future of their practice and community uncertain. Television footage and scant early coverage were essential to efforts to preserve bounce history after the storm, including the 2007 film Ya Heard Me (directed by Matt Miller, who later wrote the first scholarly consideration of bounce) the 2010 Ogden Museum multimedia exhibit Where They At: Bounce and Hip-Hop in Words and Pictures by photographer Aubrey Edwards and journalist Alison Fensterstock; and the NOLA Hiphop and Bounce Archive, a collection of new video interviews established at the Tulane University-based Amistad Research Center by musicologist Holly Hobbs during her doctoral studies there. Of course, the most important work of documentation was done, in a way, by the music itself. The lyrical convention of calling out public schools, nightclubs, and housing projects means that the landmarks and character of a certain world remain in these recordings, even after the places themselves have fallen victim to the demolition and reimagining of public housing in New Orleans, the renaming of now-charter schools, and the shortened lifespan of gathering places in low-income neighborhoods in the face of gentrification.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina (memorably documented in the immediate moment by bounce rapper Fifth Ward Weebie’s joyfully profane anthem “F- Katrina”), bounce also took on a new life. Rapper Big Freedia, who first performed as a backup dancer for Take Fo’s Katey Red, crossed over to a new, international audience via dogged touring and appearances at events that served a hip, cross-racial, indie- and punk-rock-focused crowd, and in the 2010s, collaborated with stars like Drake, Lizzo, and Beyoncé, who, as a native Houstonian, was already a fan of the sound. The Fuse TV reality show Big Freedia: Queen of Bounce ran for six seasons under that title and earned a GLAAD Media Award.