Calvin J. Roach v. Dresser Industrial Valve and Instrument Division

A lawsuit filed by a man against his employer resulted in a ruling establishing Cajuns as a federally recognized ethnic group.

National Archives

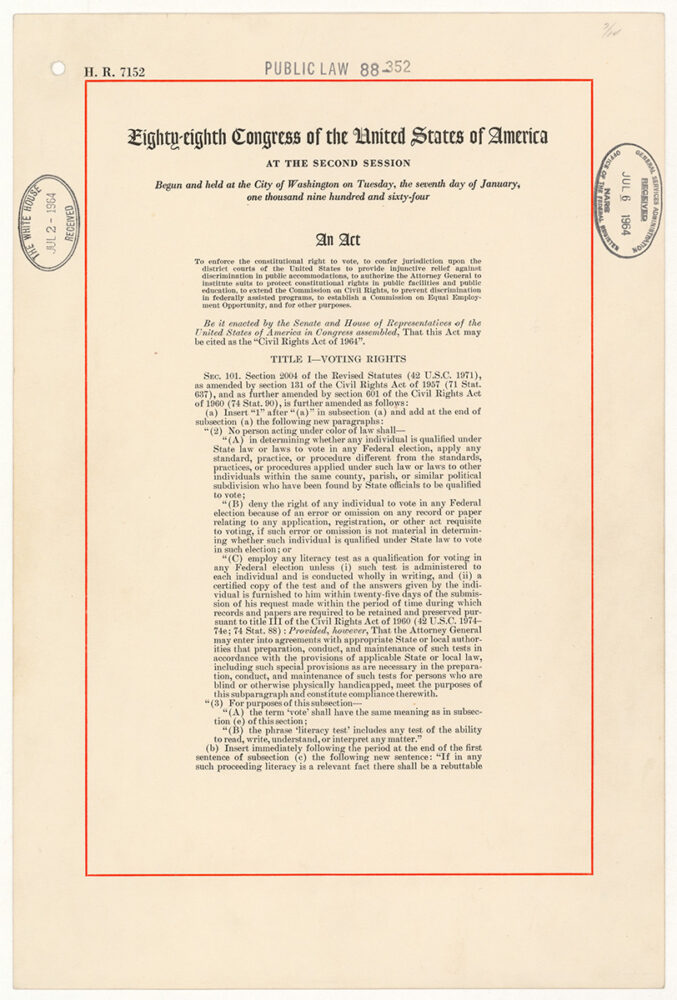

In Roach v. Dresser Judge Edwin F. Hunter ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964—which in part forbids ethnic discrimination in the workplace—applied to the Cajun people.

The legal case Calvin J. Roach v. Dresser Industrial Valve and Instrument Division established Cajuns as a federally recognized and protected national ethnic minority group for the first time. Delivered in July 1980, the ruling from the US District Court for the Western District of Louisiana resulted from a lawsuit filed by engineer Calvin J. Roach of Lafayette, who claimed Cajun descent through his mother’s Leger family.

Roach (whose French ancestors spelled the surname “Roche”) alleged his employer, Dresser Industrial Valve and Instrument Division, a petroleum company, fired him after he objected to a superior’s frequent use of the derogatory term “coonass” to refer to Cajuns. A controversial term, “coonass” is regarded by some Cajuns as an ethnic slur meaning “ignorant Cajun” or “backward Cajun”; others, however, view the term as a badge of ethnic pride, much like the word chicano among Mexican Americans. In South Louisiana, for example, some Cajun drivers display bumper stickers stating “Warning: Coonass on Board!” or “Registered Coonass” (both of which generally depict a raccoon’s posterior). The word’s origin is unclear: one popular folk etymology claims that coonass dates from World War II, when native French speakers derided Cajun soldiers as conasse, meaning “dirty whore” or “idiot.” However, this etymology has been disproved by the discovery of the word’s existence prior to America’s entry into World War II.

Despite efforts by Cajun activists like James Domengeaux and Warren A. Perrin to stamp out the term’s use, “coonass” continues to circulate in South Louisiana and beyond. Its public acceptability varies according to circumstances, and often depends on who says it and with what intent. Cajuns who dislike the term have been known to correct those who use the epithet.

Noting the term’s arguably offensive nature, Roach’s attorneys contended that Roach “was terminated from his employment with [the] defendant … because of his national origin and his association with co-employees of the same national origin, to-wit, Acadians or ‘Cajuns,’ and because he objected to excessive and opprobrious derogatory comments made by members of the management of defendant relating to co-employees who were Acadian or ‘Cajuns.’ ” Attorneys for Dresser Industries, on the other hand, argued that Cajuns could not be considered a federally protected national minority because their homeland, Acadia (now part of the Maritime Provinces of Canada), had never been an independent nation.

Judge Edwin F. Hunter, however, disagreed with the defendant’s attorneys and ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1964—which in part forbids ethnic discrimination in the workplace—applied to the Cajun people. As such, Hunter ruled in Roach’s favor, declaring that Cajuns were of “foreign descent” and therefore received protection under federal antidiscrimination laws. Hunter further declared: “By affording coverage under the ‘national origin’ clause of Title VII he [Roach or another Cajun] is afforded no special privilege. He is given only the same protection as those with English, Spanish, French, Iranian, Czechoslovakian, Portuguese, Polish, Mexican, Italian, Irish, et al., ancestors.”

Faced with this legal setback, Dresser Industries decided to immediately settle out of court with Roach rather than allow the case to advance further and risk court-imposed damages and penalties. While Roach himself rarely spoke about the case in public, the suit had a notable impact on the Cajun people. Roach v. Dresser Industries confirmed the Cajuns as a federally recognized ethnic group and undoubtedly contributed to the Louisiana State Legislature passing a concurrent resolution in 1981 condemning the word “coonass” as “offensive, vulgar, and obscene.”

Roach died at age 84 on March 24, 2010, in Lafayette.