Carville National Leprosarium

Several buildings at the National Leprosarium at Carville, Louisiana, were built by the Works Progress Administration.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

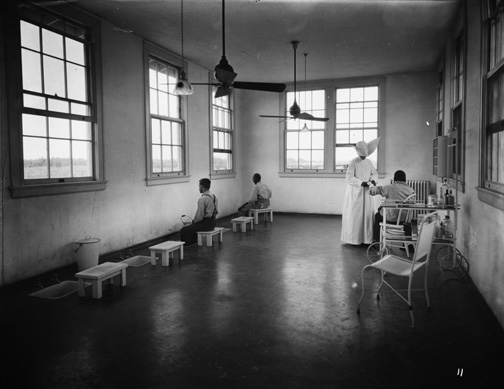

Infirmary, Carville Lepers Home. Charles L. Franck Photographers (Photography)

From 1894 to 1999, the National Leprosarium (now known as the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center) was the only inpatient hospital in the United States dedicated to the treatment of Hansen’s disease, commonly known as leprosy. Though its name has changed over the years, for many the hospital has been known simply by its location, Carville. Carville has provided a home for 4,500 victims of Hansen’s disease–once believed to be highly contagious– while simultaneously sponsoring research that led to the successful treatment of the disease in the 1940s.

Early History

Carville began its history as the Louisiana Leper Home in 1894, when Louisiana established a “hospital” for victims of Hansen’s disease on an abandoned sugar plantation known as Indian Camp. Originally built in 1859 and designed by New Orleans architects Henry Howard and Albert Diettel, the plantation house had fallen into disrepair, and as a result, the first patients were housed in former slave cabins. In 1896, four members of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul began caring for victims of Hansen’s disease, who were exiled from society under a mandatory quarantine.

At the time of Carville’s founding, leprosy was believed to be both highly contagious and morally suspect. The latter belief stemmed from biblical references suggesting that skin lesions and deformities, like those caused by Hansen’s disease, reflected God’s judgment on its victims. Though scientists proved that bacteria caused the lesions and disfigurement, and that Hansen’s disease was no more contagious than other common diseases, the stigma was slow to disappear. Victims’ family and friends were encouraged to avoid all contact or face isolation and even violence from their communities. Carville not only treated the victims of Hansen’s disease, it protected the identities of its residents, many of whom were forced to change their names and abandon their families. The disease remains the most poorly understood of the human infectious diseases, and an inordinate fear of leprosy persists to this day.

In 1905, the state purchased the property and assumed custodial care of the patients. The slave cabins were replaced with twelve cottages and a dining hall. In 1917, the US Senate passed an act establishing a National Leprosarium. After several years of “not in my back yard” wrangling, Carville was selected for the site and the federal government bought the property from the state. In 1921 the US Public Health Service took over the facility—which then had about ninety patients—and began a building drive.

Carville and the New Deal

The Public Works Administration, one of the New Deal agencies, built a new hospital at Carville in 1938. Though the facility was renamed the U.S. Marine Hospital, its mission remained the same. The new hospital—featuring staff quarters, treatment rooms offering hydrotherapy and electrotherapy, an operating room, a pharmacy, and laboratories for research—cost $340,843. The Treasury Department’s supervising architect, Louis Simon, was responsible for the Classical Revival design, built of brick with a stucco finish and stone trim. The facility quickly earned a reputation as the most advanced center for the treatment of Hansen’s disease in the world, and patients arrived from several different continents.

In 1940 the Works Progress Administration, another New Deal agency, funded the construction of new dormitories and dining facilities. The buildings were arranged around two quadrangles and linked by two-story, screened, and covered walkways.

Closing in on a Cure

Ironically, as the facilities at Carville became increasingly sophisticated and comfortable, Dr. Guy Faget, the hospital’s director, discovered a cure for Hansen’s disease. In 1941, Faget and his staff began trials with a sulfone drug, Promin, that slowly and miraculously reversed the symptoms—ulcers and skin lesions and inflammation of the throat and eyes—for most sufferers. By this time, most physicians recognized that the disease was not highly contagious. Since treatment could be provided on an outpatient basis, there was no need for hospitalization, much less quarantine.

Nonetheless, many of the residents chose to stay at Carville. For most patients, the regime of secrecy was too deeply implanted to be overcome. Writing under the pseudonym of Betty Martin, one long-time resident said, “We belong to a secret people…and must walk carefully, that no one may know we walk in a secret world.” Martin’s 1950 book, Miracle at Carville, appeared on the New York Times best-seller list. In addition, patient Sidney Maurice Levyson, writing under the name of Stanley Stein, worked tirelessly to dispense accurate information about Hansen’s disease and eradicate the use of the word “leprosy.” In 1941 he founded an influential magazine, The Star, which remains the world’s most widely distributed periodical on Hansen’s disease.

The US Department of Health and Human Services took over the management of Carville in 1982, and the facility was renamed the Gillis W. Long Hansen’s Disease Center in 1986. The facility was shared with the Federal Bureau of Prisons briefly from 1990 to 1993. The research operation was relocated to the School of Veterinary Medicine at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge in 1992. In 1999, ownership was transferred to the state and the clinical operation relocated to Summit Hospital (now Ochsner) in Baton Rouge. The 130 residents were given a choice of receiving a lifetime stipend to live independently, relocating to a chronic care facility at Summit Hospital, or remaining at Carville in leased space under assisted living conditions.

At Carville, the Louisiana National Guard implemented a new program, called Youth ChalleNGe (with the capital letters to emphasize its National Guard sponsorship) to provide skills and boot-camp conditioning to at-risk teenagers. Carville thus continues a tradition as a place where people from adverse circumstances can build new lives. The facility now includes the National Hansen’s Disease Museum, open to the public.