Confederate Louisiana

As a member of the Confederate States of America, Louisiana provided soldiers who fought outside the state.

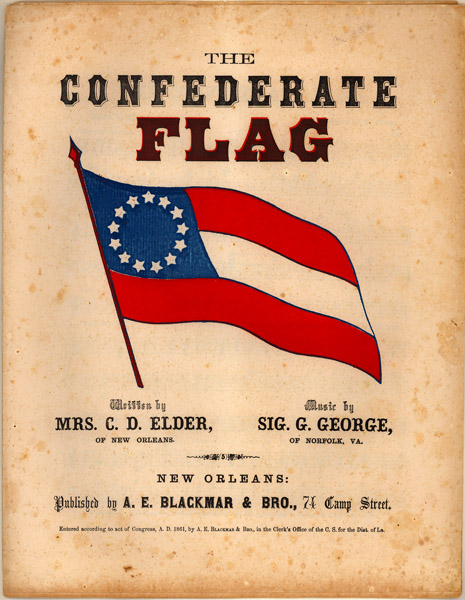

Courtesy of Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University

The Confederate Flag. A. E. Blackmar & Brothers (Publishers)

On March 21, 1861, two months after Louisiana had seceded from the United States, the state officially joined the Confederacy. The state’s membership in this new nation was characterized by a combination of cooperation and friction.Many Louisianans complained that while the state had provided much for the Confederacy, especially soldiers, the Confederacy had offered little in return. In December 1862, Governor Thomas Overton Moore bluntly asked President Jefferson Davis, “What has been done for Louisiana?” In the governor’s view, the simple answer was “nothing,” and consequently Louisiana would have been better off if it had maintained an “independent sovereignty.” Nevertheless, despite such statements, Governor Moore and the majority of other Louisianans remained loyal to the Confederacy from its inception to its defeat.

In the first year of the conflict, Louisiana provided the Confederacy with approximately 25,000 troops. During the war, this number would increase to between 50,000 and 60,000 men. Upon their enlistment, most Louisiana soldiers immediately left the state to fight in the eastern theater. The Confederate government maintained that Louisiana would be best defended in Virginia. Thus, despite New Orleans’s status as the Confederacy’s largest city and most important commercial center, the city was defended only by two downriver forts. Consequently, when the Union navy steamed up the Mississippi River in April 1862, New Orleans surrendered without bloodshed. The fall of New Orleans put about one-quarter of the state’s total population (and more than 40 percent of its white population) behind enemy lines, made it impossible for most cotton and sugarcane growers to get their corps to market, and made the state’s capital at Baton Rouge untenable. Consequently, as the borders of Confederate Louisiana contracted, the state legislature moved to Opelousas in 1862 and subsequently to Shreveport in spring 1863.

Despite the shrinking of Confederate Louisiana, the national government in Richmond never made it a military priority. Initially, it placed the defense of New Orleans in the hands of the sickly, barely ambulatory, 71-year old General David Twiggs. Then, after the fall of the Crescent City, the Confederacy divided Louisiana among three separate commands, none of which had a headquarters within the state. After repeated complaints, the Confederacy sent General Richard Taylor , a Louisiana plantation owner and the son of President Zachary Taylor, to command the few troops within the Pelican State and to recruit new men. In 1862 and 1863, Taylor found himself in command of only 5,000 to 10,000 soldiers. Later, most of Louisiana was added to the Trans-Mississippi Department, under the command of General Edmund Kirby Smith, who based his headquarters in Shreveport. Unfortunately, some of the value of Smith’s presence was undermined by a feud with General Taylor over the best way to defend the state.

Louisiana provided the Confederacy with a number of able leaders. Both of the state’s governors, Thomas Overton Moore and Henry Watkins Allen, epitomized the balance of cooperation and conflict with the Confederate government. In particular, Allen, who headed the state from January 1864 until the end of the war, received praise for his ability to balance the needs of Louisianans and national leaders, and some historians consider him one of the Confederacy’s greatest governors. Both Moore and Allen championed Louisiana’s interests, but, in contrast to some governors of other Confederate states, they did not impede the recruiting or supplying of the Confederate army in doing so.

Protests against the Confederacy

While the state’s governors accepted the Confederate government’s requests, not all Louisianans joined them in acquiescence. Their protests focused mainly against three main policies: conscription, impressment, and the tax-in-kind. Some complained that conscription, which forced most able-bodied men into the army, threatened their liberty, while others believed that the operation of the policy compelled the poor to fight while allowing the rich to remain safely at home. Impressment forced people to sell goods at fixed prices that were often below market value, and the tax-in-kind entitled the government to seize 10 percent of each crop. Many Louisianans disliked the arbitrary application of these crop purchase and crop seizure policies. Some regions never witnessed either measure, while other areas faced both the tax-in-kind and repeated impressments. Additionally, many Louisianans considered these policies to be unconstitutional government infringements on their property rights. Others griped more generally about the Confederacy’s inability to combat privation in Louisiana—a severe shortage of food and supplies—rather than about specific policies.

The strongest opponents of the Confederacy would become unionists fighting for the North. More than 5,000 white Louisianans, many of them immigrants living in New Orleans, fought for the Union (joining an additional 24,000 African Americans from the state). Nevertheless, opposing Confederate policies did not necessarily equate to unionism. Instead, many Louisianans rejected both Union and Confederate governments. These people often formed jayhawker bands determined to resist any encroachments on their liberty. Estimates on their numbers vary, but most agree that thousands of Louisianans resisted both the Confederacy and the Union in this manner.

Undoubtedly, however, loyal Confederates outnumbered unionists and jayhawkers in the state. Not only did Louisiana provide more than 50,000 troops to the Confederacy, it also supplied a number of important leaders. Leading generals from Louisiana included Braxton Bragg, Leonidas Polk, Richard Taylor, and Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. Additionally, several of the Confederacy’s prominent politicians hailed from the Louisiana. Former US Senator Judah P. Benjamin proved to be one of Jefferson Davis’s most trusted advisors. (Ironically, in 1853, Senator Benjamin had challenged Davis to a duel after Davis insulted him on the Senate floor. The duel was averted and the men became friends.) During the first twelve months of the conflict, Benjamin was the Confederacy’s first attorney general, then secretary of war, and finally secretary of state, a position he held from March 1862 until the end of the war. In his efforts to achieve foreign recognition of the Confederacy, Benjamin relied on several fellow Louisianans. Throughout the war, John Slidell represented the Confederacy in France. In 1864, Davis and Benjamin appointed one of Louisiana’s wealthiest plantation owners, Duncan F. Kenner, who was serving as chair of the Ways and Means Committee in the Confederate Congress, on a special mission to England and France to see if those two nations would recognize the Confederacy in exchange for the emancipation of southern slaves. He did not arrive in Europe until 1865, and by then the question of foreign recognition was a dead letter.

Regardless of the efforts of Confederate Louisianans, their bid for independence failed. On May 26, 1865, General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered his forces, the last major Confederate army in the field, officially ending the Civil War in Louisiana. Louisiana’s membership in the Confederacy lasted just over four years, though the effects of this affiliation would last much longer.