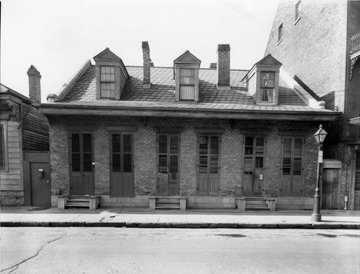

Creole Cottage

The French-designed Creole Cottage was a major urban house type in New Orleans during the early 1800s.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Six Bay Creole Cottage. Charles L. Franck (Photographers)

The Creole Cottage was a major urban house type in New Orleans during the first half of the nineteenth century. Unquestionably of French origin, these cottages, while small in size, make use of typical eighteenth-century French planning rules, the most important of which is the omission of any sort of interior hallway.

The early examples of this house type were often placed close to the ground, with only a minimal foundation. The street facades usually contained four openings: either two full-length entrances fitted with French doors, the upper sections of which were glazed, and two windows, all of which were held hinged to open into the house; or four doors with no windows. On some of the early cottages, the openings were round arches, with fanlights of glass fitted into each arch. The facades were flush with the front property line, with no front setback or yard, conserving the private space to the rear of the house for a yard. These early designs were most often of briquette-entre-poteaux (brick between post) construction, which was covered over with plaster to protect the poor-quality brick made in the city at that time. The typical Creole Cottage roof was covered by wood shingles, boards, or strips of bark and was steeply pitched, providing sufficient rain runoff as well as insulation from the pervasive heat.

At roof level, projecting from the top of the front wall was often an overhanging canopy, which was supported on iron rods and offered protection from rain and sun. Elegantly detailed dormer windows often broke the slope of the roof, providing light and ventilation to the upper half-story. To access the interior, one would enter the two front rooms, which were reserved for the family and their guests. Behind them, a second set of rooms was considered private space for family use only. The fireplaces required to heat the house were most often placed on the partition wall that divided the house down the middle, with a chimney rising above both the front and rear slopes of the roof. The mantelpieces made use of either pilasters or full columns as the vertical members flanking the hearth and supporting the mantelshelf. At the rear of the main house, facing onto the yard, two small rooms called cabinets projected from either end of the back wall. These spaces were used for storage, and one was often the site of the stair to the upper floor, where additional bedrooms were located. Toward the rear of the lot, and sometimes on the side of it, was the detached kitchen building, often with a second floor. Fear of a cooking-related fire prompted the decision to separate the kitchen from the main house.

Later examples of the Creole Cottage show a progression in terms of architectural detailing, with the protective overhang now made part of the front slope of the roof, replacing the older cantilevered canopy. The houses were also placed on higher foundations, which required small flights of steps to reach the doors. Such placement was perhaps a way to avoid the dirt and water that came from the unpaved streets, a problem that was noted in 1834 by John H. B. Latrobe, son of the noted architect Benjamin Latrobe, in his diary.

Increasingly, the cottages’ exteriors had wood weatherboards for their exterior finish, but builders often continued to use brick-between-post construction for the exterior walls, which was protected by the weatherboard skin. Elements of the more American Greek Revival style can also be seen, most notably, in the mantel details, which now took the form of the eared or crossette, where the molding of the mantel’s horizontal section projects beyond its vertical sections.

Eventually, the American practice of placing a hallway in a house would become a part of the Creole Cottage form, essentially eliminating its most important feature: an interior plan with no hall or passage.

The Creole Cottage house type is distinctive to two areas of New Orleans: the French Quarter and the adjacent Faubourg Marigny just downriver. The houses were the products of builders and owners who were of French descent or free people of color, some of whom had come to New Orleans from Haiti in the first decade of the nineteenth century. Thus, the homes testify to the ethnic and racial mixture of the city’s population at that time.