Creole Folktales

Many Louisiana Creole folktales represent a convergence of African and European culture.

Courtesy of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities

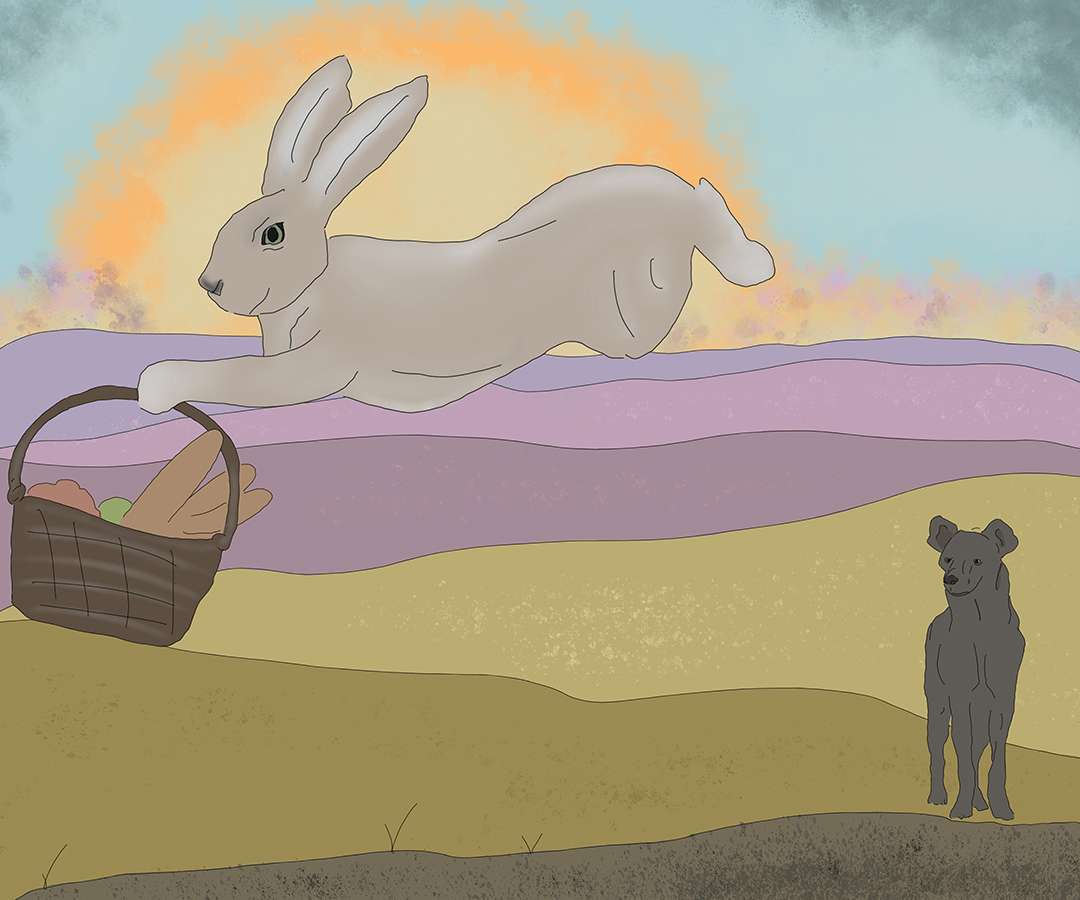

An Illustration of Lapin and Bouki by Cecilia Tisserand, 2022.

Creole folktales are part of the oral tradition of Louisiana’s Creole communities who reside mainly in the Bayou Teche region; the prairie region of Lafayette, St. Landry, and Evangeline Parishes; Pointe Coupée; the River Parishes; and New Orleans. Many of the folktales found in the Louisiana Creole repertoire represent a convergence of African and European (especially French) influences. Due to the multiple meanings of the term “Creole,” there is an understandable degree of overlap between Cajun and Creole traditions and cultures as well as shared folklore elements. This article focuses on some of the most notable examples of Afro-Creole folklore in Louisiana.

Some of the earliest written examples of Creole folklore were transcribed by Alcée Fortier. Fortier was a linguist who studied the grammar and structure of Louisiana’s Creole language (also known as Kouri-Vini). The stories in his collection Louisiana Folk-Tales (1895) were told to him by Black Creole storytellers both in New Orleans and his native St. James Parish. The collection contains many examples of the strong influence of African storytelling traditions, demonstrated in part by the large cast of animal characters. The animals are often humanized by an honorific title such as “Compair” (Compère) and exhibit specific character traits. Etiological tales (or “why” tales) are common, such as “Compair Lapin et Madame Carencro,” which tells of how Compair Lapin pours hot embers on the heads of Madame Carencro and her family of buzzards, which is meant to explain why buzzards’ heads are bald.

Many Creole animal tales feature a trickster figure who defies larger and stronger creatures through his or her cleverness. Lapin (“rabbit” in Louisiana French and Creole) is the most renowned of the animal tricksters in this repertoire and often plays tricks on Bouki, whose name is derived from the Wolof word for “hyena.” Such tales highlight strong West African and Caribbean influences as well as their adaptation to the sociocultural context of Louisiana, as is visible through the mingling with European elements and the heightened prestige of the trickster figure. As Lawrence Levine and many folklorists have noted, the collective trauma of slavery brought about the need for a shift in some of the morals promoted in folktales to convey the importance of wit and strategy as a means of survival. This is evident in cycles of tales featuring enslaved protagonists who defy their oppressors through their wit and trickster-like actions. These kinds of themes and morals continued to be relevant during the Jim Crow era during which people of color often endured harsh racial discrimination and violence.In addition to more narrative forms of folklore, there are also several other Creole folklore figures that illustrate the fusion of African, Afro-Caribbean, and European cultures. For example, the fifolé in Pointe Coupée Parish derives its name from the French feu follet (the will-o’-the-wisp); however, it is more closely related to the Caribbean figure, the soucouyant. This vampire-like figure disguises itself as an old woman during the day. However, at night it removes its skin and travels through the air in the form of a ball of fire seeking the blood of children. Folk belief maintains that to vanquish the fifolé, one must find the skin where it was left and sprinkle salt and pepper upon it. Once the fifolé returns to replace its skin before sunrise, it will be burned.

Often the cultural mélange of Creole folklore is evident in the presence of traditional folk belief and elements of Catholicism. Kooshma—or sometimes called couche-mal—comes from the French cauchemar (“nightmare”), which itself was originally used to refer to an evil spirit causing sleep paralysis. Familiar to many Creoles of color, kooshma is generally thought of as a malevolent spirit and often portrayed as a female entity or succubus who holds her victim down during restless sleep. The real phenomenon of sleep paralysis (also known as “old hag” syndrome) has given rise to a variety of folk beliefs to explain the condition. In the case of kooshma, it is often considered a result of one’s moral missteps or as a punishment for recent sins. A variety of prayers or religious objects, such as rosaries or holy medals, are said to be effective at keeping kooshma from returning.

Creole folktales have continued to be collected throughout the twentieth century by folklorists such as the stories of Wilson “Ben Guiné” Mitchell and others recorded by Barry Jean Ancelet. More recently, Louisiana Creole folklore has served as inspiration for numerous children’s books as a form of cultural revival of the oral tradition.