David Allen

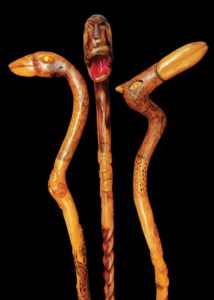

David Allen was a walking stick carver from Homer, Louisiana. His work often includes the heads of men, animals, and snakes combined with elements of popular culture.

Michael Sartisky, Ph.D.

David Allen uses the roots of young saplings to form the handles of his carved canes, and looks at the root shape to “see” what animal or other shape is evident.

Tavid Allen was an African-American walking stick carver from Homer, Louisiana. Initially products of the traditional southern pastime of whittling and wood carving, Allen’s carving style and designs exhibit singular forms and innovative technique development that have propelled him from relative obscurity in rural North Louisiana to recognition on both a regional and national level.

Born in Claiborne Parish in 1925, Allen began whittling toys as a boy. His first tries at whittling were accomplished with a pocketknife, which he had found under his family’s house. He had to keep the knife hidden and work on the sly because he was considered too young to be playing with knives. He learned to make simple toys such as slingshots and, later, utilitarian objects such as shoeshine boxes. Allen’s inspiration to make walking sticks came to him rather unintentionally at about age fifteen: After carving the bark of gum saplings, he found that as the wood dried, the bark—and hence the design—peeled off.

Although Allen does not remember seeing any carved walking sticks during his youth, he does note that in his community, sticks were commonly cut and used in walking, especially at night, as an aid for sure footing and a weapon for warding off dogs and other potential attackers. Allen’s family did have a history of woodworking. His father, a farmer, made white-oak baskets and hickory ax handles, and passed on his expertise with wood to his son. Whittling was also a common pastime in the surrounding rural community. Thus, Allen’s walking-stick carving emerged as an extension of this background.

Allen forgot about his first foray with stick carving for years as he became busy with his various jobs as porter, grocery boy, carpenter, logger, and plumber, along with raising his and his wife’s six boys. When he became disabled by a heart condition and cataracts in the 1960s, he began carving again. While on a fishing trip, he saw some hickory saplings, tempting him to try carving another stick. The hickory retained its bark when it dried, making it a better medium for his incised carving. After carving several sticks in this manner, he began stripping away the bark and carving the underlying wood.

Through the years, Allen honed his techniques and developed a repertoire of motifs. His 1979 canes show his improvisations on the carved shaft with a variety of complex spirals, stripes, diamonds, and floral designs—the latter he called four-leaf clovers, which he believed bring good luck. The motifs appearing on the early cane handles include the heads of men, animals, and snakes naturally prominent in his rural surroundings, along with elements of popular culture, including cartoon characters such as Snoopy, the Pink Panther, and spacemen. Colored glass stones and beads from Allen’s wife’s costume jewelry accent features on his figures. Dark colors, achieved through burning the wood with a propane torch, contrast sharply with the natural wood color and highlight his designs. Allen’s early tools included a hatchet, hacksaw, pocketknife, wood rasp, glass, and sandpaper.

Allen’s techniques, designs, and the carved cane itself were self-devised. He would dig around the root of a sapling to see what designs the root brought to his mind, believing that he must “see” the design in the particular piece of wood before he cut it. This reflects the creative processes of other African-American artists. His ideas, rather than being handed down to him from another wood carver, came to him in visionary flashes or sometimes in dreams.

Gradually, Allen’s work gained greater recognition. The first festival he participated in was in his hometown of Homer in 1979. The next year he demonstrated his craft at the Natchitoches Folk Festival. Allen’s work was also featured in an exhibit and accompanying booklet produced by the Alexandria Museum of Art in central Louisiana, where one of his sticks remains in the permanent collection. After this event, Allen’s popularity began to grow rapidly and he was invited to participate in many other festivals. In 1981 and 1985, Allen and his wife, Rosie Lee, who is a quilter, were invited to participate in the Festival of American Folklife sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Allen considered his trips to Washington, D.C., the high points of his career. One of his most prized sticks is on display at the Smithsonian and more are in The Creole State: An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife in the Louisiana State Capitol. Other festivals that have provided opportunities for Allen to demonstrate his craft and sell his sticks include the Red River Revel, the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and the Louisiana Folklife Festival.

David Allen died on August 28, 2014.

Adapted with permission from Public Folklore, The University Press of Mississippi, 2007.