Dom Gregory de Wit

In 1946, Benedictine artist Dom Gregory de Wit began working on his brilliantly colored, large scale murals for the St. Joseph Abbey near Covington, Louisiana.

Courtesy of Saint Joseph Abbey

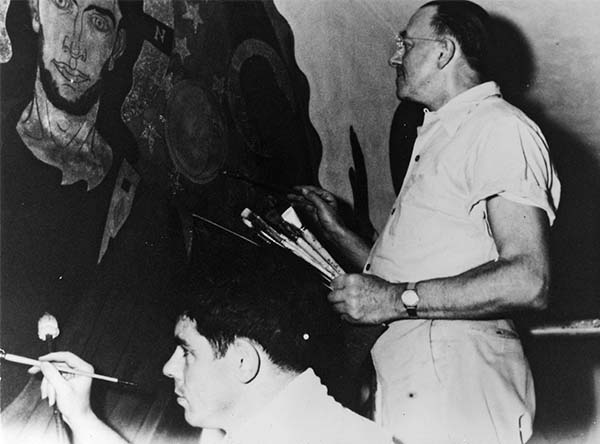

Dom Gregory de Wit painting. de Wit, Dom Gregory (Artist)

Dom Gregory de Wit, a Benedictine monk of the Abbey at Mont César in Louvain, Belgium, created vivid murals and three-dimensional Stations of the Cross that adorn St. Brigid Catholic Church in San Diego, California, St. Meinrad Archabbey in St. Meinrad, Indiana, and several churches in Louisiana. His most notable work is found at St. Joseph Abbey and Seminary College in St. Benedict, near the city of Covington.

De Wit was born in Hilversum, The Netherlands, in 1892, at a time when the village was transforming into a prosperous rail suburb of Amsterdam. He entered the monastery at Mont César in 1913 and was ordained there in 1915. The Benedictine community has a tradition of supporting the fine arts, and de Wit’s superiors encouraged his artistic talent. He studied art at the Brussels Academy of Art, the Munich (Germany) Academy, and in Italy. In 1923 at The Hague, De Wit exhibited forty-five works at his first art exhibit, selling out the complete collection. De Wit also won acclaim for designs in glass.

Art Commissions in America

Abbot Ignatius Esser of St. Meinrad Archabbey in southern Indiana saw de Wit’s murals in Benedictine monasteries and convents during a trip to Europe in 1937. Esser asked Abbot Bernard Capelle of Mont César to allow de Wit to travel to the United States to paint murals at St. Meinrad’s abbey church. Capelle granted permission, and de Wit arrived at St. Meinrad in April 1938. Over three months, de Wit designed a 47-by-24-foot Byzantine-style mural of Jesus in the apse of the abbey church.

The Reverend Columban Thuis was a popular speaker and retreat leader among Benedictine monks. In 1931, while rector at St. Meinrad, Thuis had come to St. Joseph Abbey in St. Benedict to conduct a community retreat. The following year, the monks of St. Joseph fondly remembered the Indiana monk and elected him as their abbot. Thuis led St. Joseph’s for twenty-five years, a period that saw many trying times, including the Great Depression, World War II, and the postwar expansion of the seminary. But one of his chief contributions was his invitation to Dom Gregory de Wit to come to Louisiana.

During a visit back to St. Meinrad, Abbot Thuis had seen de Wit’s mural and thought immediately of his Sicilian-born friend, Monsignor Dominic Blasco, who was completing the construction of his Baton Rouge parish church, Sacred Heart of Jesus. Thuis made the introductions and facilitated the necessary connections, and Blasco invited de Wit to paint a Byzantine-style mural of Jesus in his new church. De Wit completed the mural as well as paintings of St. Mary Magdelene, Sts. Peter and Paul, St. John the Baptist, the Samaritan woman at the well, and the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

De Wit finished his work in Baton Rouge and, in 1946, accepted Thuis’s invitation to move to St. Benedict. He would remain there for ten years. Churches in New Orleans—St. John the Baptist, St. Raphael, and St. Pius X—as well as St. Gertrude in Des Allemands, also display de Wit’s paintings and sculpture. His most accomplished masterpieces, however, fill the spaces of the refectory (dining room) and church of St. Joseph Abbey.

St. Joseph Abbey Murals

De Wit began his work by planning a huge mural—five feet wider than da Vinci’s, as de Wit would later say—of the Last Supper that fills one wall of the refectory. The key element of the room’s theme of “salvation through eating,” the Last Supper mural displays Jesus at the head of a horseshoe-shaped table just at the moment that he offers bread and wine to his apostles. Across the room, de Wit painted a mural of the youthful Christ the Good Shepherd, a beardless Jesus hoisting a lamb onto his shoulders. Other images in the refectory include biblical stories, saints, astrological symbols, and scenes from nature. Fifty-six ceiling panels—arranged in four rows of fourteen—center on the four basic elements of earth, water, air, and fire. De Wit united the disparate images with the theme of Christ as lord of all creation. He continued this theme throughout the abbey church.

But before beginning the second part of this formidable task, de Wit became a US citizen and left for Italy to tour churches decorated with Byzantine art in 1950. While in Europe, he met a young Swiss monk, Milo Piuz, whom he hired to return with him to Louisiana to execute his plans for the abbey church. Soon after January 1951, when the St. Joseph Abbey community voted to approve Thuis’s continued employment of de Wit (and Piuz), de Wit began the church murals.

De Wit portrayed Christ Pantocrator in the church apse as the risen Christ who is also Christ the Creator, in a central image surrounded by Adam and Eve and a flock of sheep that represent God’s creation. De Wit discussed the complex theology when he was invited to “explain” his work upon its completion in 1955. The main idea, he said, is unity in Christ: “Christ is everything and we are in Him. He is the Alpha and the Omega. There is the beginning [pointing to the image in the apse] and there is the end [pointing to the image of Christ the Judge in the rear of the church]. . . . We come home from the Alpha and we go home to the Omega. We have to pass through this corridor [of life], this immense church, which is Christ.” In the center of the church in niches that once held side altars, de Wit painted six male saints and six female saints as representative of “invisible creation,” of the souls created by God. De Wit reminded the young seminarians, “You are one with all those saints. Your souls are invisible creations.”

In de Wit’s mural in the rear of the church, ordinary folks who represent every class, age, and ability approach Christ the Judge. Without fear of condemnation come a young boy with polio, a blind boy, a businessman chomping on a cigar, a little girl bearing a bouquet, an older girl, a woman bowed with age, another bowed with grief holding a dead child, a soldier, a bishop, an injured man on crutches, a pope, a nun, Moses or some other church patriarch, a worker holding a pick and shovel, and a humble monk holding paint brushes and a palette.

No matter the subject, De Wit’s murals are unique in their impressive faces with sculpted bone and taut muscles, slightly out-of-scale hands and feet that nonetheless convey life and vitality, and clothes of vibrant texture that seem to extend out of the picture plane. De Wit drenched his images with striking colors that remain brilliant sixty years later. He mixed his own paint from powdered pigments and potassium silicate, a compound that has endured well on the plaster walls of the humid grounds of St. Joseph Abbey.

De Wit returned to Europe in 1955 and lived in Switzerland until his death on November 22, 1978. He is buried in Oberems, Switzerland.