E. J. Bellocq

Photographer E. J. Bellocq gained fame after his death for his portraits of prostitutes in Storyville.

Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery.

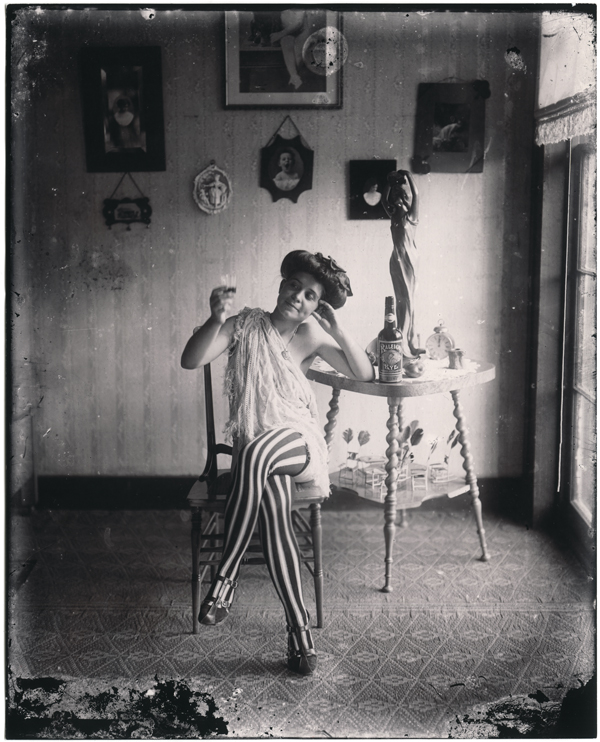

Black-and-white reproduction of a photograph by E. J. Bellocq of a prostitute in Storyville, c. 1912.

New Orleans photographer Ernest J. “E. J.” Bellocq gained posthumous fame for his portraits of prostitutes made in Storyville, the legalized red-light district of New Orleans. Relatively little is known about Bellocq or his reasons for making the portraits; eighty-nine glass negatives for the photos were discovered after the photographer’s death. Though the photos appear to have been made around 1912, they did not come to the public’s attention until the early 1970s, when photographer Lee Friedlander exhibited them at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and published a group of them in Storyville Portraits.

Early Life and Career

Born August 19, 1873, in New Orleans, E. J. Bellocq was the son of Paul Bellocq and Marie Aldige Bellocq. Census records indicate that Bellocq’s paternal and maternal grandfathers migrated to the United States from France. He appears to have been raised in a Catholic household and his younger brother, Leon, eventually became a Jesuit priest. Between about 1895 and 1940, E. J. Bellocq made his living as a commercial photographer in New Orleans. Though little of his work as a commercial photographer seems to have survived, it is known that around 1918 he served as company photographer for a shipbuilding firm.

It is possible that Bellocq’s Storyville photos were made for commercial purposes; photographs of prostitutes were made for Blue Books, advertisements created by New Orleans’s brothels. It seems more likely, however, that Bellocq knew the women in his photographs. The relaxed appearance of the prostitutes featured in the photos suggests that Bellocq took the pictures for himself or for the women, rather than for commercial use. Most of the photos are portraits of individual women, photographed in full figure from a slight distance. While some appear fully clothed, many of the women appear in various states of undress. Virtually all the photos indicate the subject’s awareness of the camera and a willingness to pose and sometimes even play for it.

Adding to the mystery surrounding the photos are several pictures in which part or all of the woman’s face has been scratched off the glass plate negative. No one knows why the negatives were literally defaced, though the evidence suggests that Bellocq may have done it himself. Perhaps he was trying to hide the identity of the prostitute, knowing that she may have wanted to conceal her profession from her family. Alternatively, some have suggested that Bellocq became angry with particular women and took his fury out on the negatives.

Discovery of the Storyville Photos

Photographer Lee Friedlander bought Bellocq’s 8˝ × 10˝ glass plate negatives from Larry Borenstein, the owner of a New Orleans art gallery, in 1966. Borenstein reportedly obtained the negatives, some of which were damaged and broken, when the contents of Bellocq’s apartment were sold after the photographer’s death. Utilizing a process that Bellocq himself might have employed, Friedlander was able to develop eighty-nine prints. In 1970, a group of these prints was exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art in New York and included in the book Storyville Portraits. An expanded and revised edition, Bellocq: Photographs from Storyville, was published in 1996.

The discovery of the Storyville pictures stimulated interest in Bellocq’s other work. His contemporaries reported that Bellocq made a series of photographs in New Orleans’ Chinatown, but none of these photographs or negatives has ever been located. He died in New Orleans on October 3, 1949. In 1978, Louis Malle directed a film loosely based on Bellocq’s life, called Pretty Baby. Bellocq’s portraits also inspired the poems in Bellocq’s Ophelia by Natasha Trethwey.