Edgar Degas

French impressionist painter Edgar Degas stayed with his Creole relatives in 1872 and 1873, and did some of his important works in New Orleans.

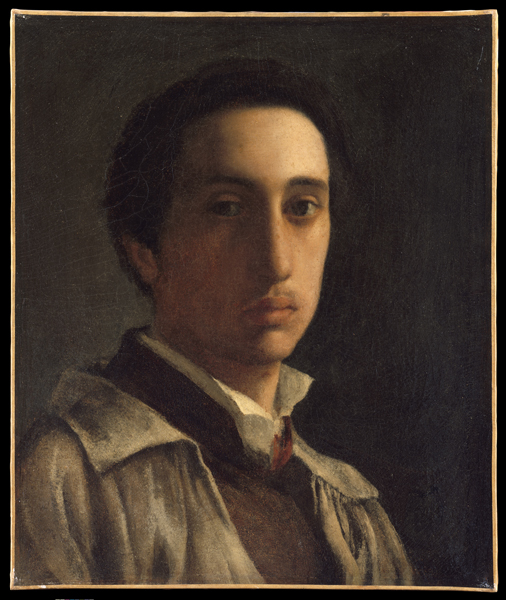

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Color reproduction of a self-portrait by Edgar Degas.

When Hillaire Germain Edgar Degas arrived in New Orleans for a visit in 1872, he was years away from being the famous French impressionist painter whose works the world would treasure. However, several of Degas’s most admired pictures, chief among them A Cotton Office in New Orleans, were begun during the period he spent visiting his family in America, from October 1872 through March 1873. Degas’s impressions of Louisiana remained with him after his return home, particularly the scenes of children, sick rooms, and domestic musicales he had witnessed. He later finished in France several of the pictures he had begun in New Orleans, including another version of cotton merchants.

Degas’ Family in New Orleans

Degas first met his Creole cousins during the American Civil War, when his aunt fled to Paris with her daughters, Désirée and Estelle, and Estelle’s baby. Degas and his brothers, René and Achille (who spelled their surname De Gas) developed a deep fondness for the women during their three-year stay. After the war, René decided to move to New Orleans in 1865 and was followed by Achille in 1866. They joined their maternal uncle, Michel Musson, in his business. René had fallen in love with Estelle (whose husband had died in the war), and they married in 1869.

Michel Musson was a cotton factor, a broker who received shipments sent downriver by planters along the Mississippi River. He registered, graded, insured, and stored the cotton until he could find purchasers for it. He then reshipped it to mills in the North or abroad. The factor worked for a commission; he succeeded or failed along with the growers he represented. Before the Civil War, New Orleans had been the country’s largest cotton port. but the devastation of the plantations during the war, the disappearance of the slave labor force, and the hardships wrought by Reconstruction had destroyed the cotton business. Musson had to sell his Garden District mansion and rent a house on Esplanade Avenue, where all the family lived together. Nevertheless, the De Gas brothers were eager to plunge into what they believed was the country’s bustling commercial mentality. “America,” wrote René, “is the country for young men with nerve.”

Impressions of New Orleans

If Degas was looking forward to this American freshness, what he found instead in New Orleans was charm and provinciality. The city’s Creoles knew English, but they all spoke French and kept abreast of French affairs. But whereas Paris was a French city of 2.5 million, New Orleans was a French town of fewer than 200,000, many in mourning for their antebellum way of life.

During the first weeks of his visit, Degas was impressed by the lake, the river, and especially the space—compared with European towns and cities, all US towns seemed underpopulated. But he was dismayed by the poverty and filth. Animals came and went through the French Quarter; hogs wandered past Musson’s office in the business district on their way to the slaughterhouse. On the coldest night of the year, sixty-two “homeless creatures” were sheltered in Charity Hospital. The diseases of a port city also disquieted Degas. Along with their cargoes and immigrant laborers, ships brought tuberculosis, plague, and smallpox. Forty-three people died from cholera the week Degas arrived, despite the availability of medicines guaranteed to cure not only cholera (in twenty minutes) but also “syphilis, consumption, and worms.” Paris, too, was full of bacilli and snake oil, but the contagions of New Orleans were more proximate to Degas. Four of the nieces and cousins he painted during his visit would die of scarlet fever or yellow fever.

At Christmas, Estelle gave birth to another child, and Degas became the child’s godfather. Now surrounded by six children, Degas found that the Musson household was wearing on his nerves. Nor was he entirely satisfied with the portraits he was producing of the family. He wanted to start a major work, but could find nothing to inspire him. New Orleans, with its riverboats, its old architecture, and its colorful people, was quaint, but he was bored with the picturesque. He had once expressed pride at the way his brothers could “talk cotton,” but now he realized that people in New Orleans talked of nothing else. At some point, however, the subject that had irritated Degas for three months began to engross him. With only a few weeks left of his sojourn, he began his major painting—a scene from his uncle’s cotton office. A Cotton Office is his portrait of those men who lived by and for cotton.

He delayed his return home for two more months, probably in order to get further along in the work. He needed to return to France to put his affairs in order and begin making some money from his paintings. But with the pictures Degas had done of his Creole relatives and New Orleans scenes—paintings such as Estelle Musson Balfour—the artist had already begun to develop his characteristic gifts: the ability to project ambiguous mood and to portray enigmatic psychological states.

A Cotton Office

Degas’s painting reveals much about the working of cotton exchanges in the South. Musson’s company dealt with ginned cotton that arrived in ragged bales of about 500 pounds. For each bale stored with the Musson firm, the planter received a negotiable warehouse receipt. The men in shirtsleeves at the extreme right of the picture may be recording these receipts—an important duty, for it was only through receipts that cotton passed from one buyer and seller to another on its way to a final, distant purchaser.

There was great variation within a shipment, so each bale was classified individually, according to its color, smoothness, and the amount of foreign matter it contained. Degas’s uncle is in the foreground of the picture with a pile of cotton next to him. He is “pulling the staple” of the cotton between his thumb and forefingers to determine the average length of the staple, or fiber, in a particular bulk.

The table in the middle contains samples, for the office is also a salesroom. The man holding up a handful of cotton is a “spot broker.” His customer, on the other side of the table, may be a mill buyer making a large purchase on the basis of those samples. The sample table resembles a gaming table, as well it might; the cotton business was highly speculative. At the nearby cotton exchange, cotton futures contracts were bought and sold. The contracts traded there were reported in the Daily Picayune, the paper being read by the man at the center of the picture—Degas’s brother René.

Degas intended the picture for a European cotton merchant—someone who perhaps knew everything about cotton and nothing about New Orleans. He left out details that might have distracted a foreign viewer, such as the black porters who were usually present in cotton offices, carrying samples back and forth to storage. Degas’s aim was not a literal representation of a cotton office, but a portrait of the American business style: self-absorbed, but at the same time informal. His point is not to show us cotton—the plant on the table could just as well be sugar or rice—but rather, occupation. Europeans thought of America as one modern, buzzing company that was also somehow relaxed and friendly.

In reality, the cotton business, as Degas knew, was haunted by failure. His uncle’s cotton office would be bankrupt before the painting was finished, its illustrated bustle having been an artist’s fiction. The relaxed postures of the men and their air of pleasant expectation are also artificial. Several of the men portrayed were to face more or less tragic experiences within a few years. Achille, leaning against the window ledge, would shoot a man in Paris, having picked up the habit of carrying a gun in New Orleans. René, in the center with the newspaper, would abandon his blind wife and children to run off with another man’s wife and children. His father-in-law, Michel Musson, pulling the staple with his back to René, would then turn his back forever on the Degas brothers.

But of course, the figures are not literally Degas’s relatives; they are profound expressions of America’s obsession with success. If the figures in Degas’s cotton office are men with prospects or men with nerve, it is because the office is not “in New Orleans” but in a psychological space where Degas trapped a powerful but ephemeral abstraction—the European idea of American enterprise.