Fall of New Orleans and Federal Occupation

Federal forces occupied New Orleans, a strategic city at the mouth of the Mississippi River, from 1862 until the end of Reconstruction.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

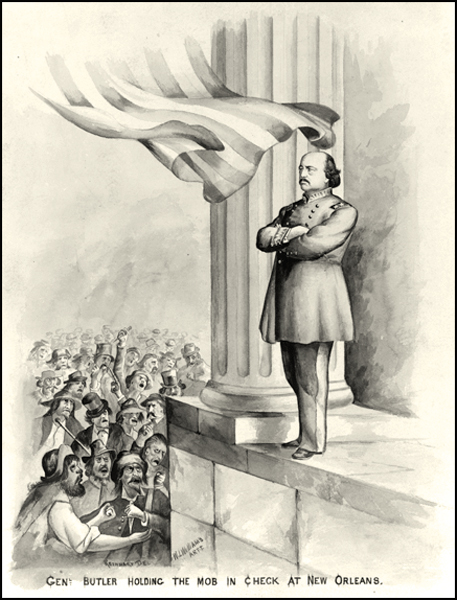

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

An illustration of General Butler in New Orleans by Charles Stanley Reinhart.

Who was living in New Orleans before the Civil War began?

Immediately before the Civil War, the population of New Orleans was approximately 170,000, with an additional ten thousand people living in the surrounding areas of Algiers, Jefferson, and Carrollton. About 47 percent of the population was white and native born. About 38 percent of the population was foreign born. The last approximately 14 percent of the population was almost equally divided between free people of color and enslaved men, women, and children. Because of oppressive state legislation toward free Black people, the population of free people of color in New Orleans actually declined in the decade before the Civil War.

During this time, the three dominant immigrant groups were Irish, German, and French. It was easy for French immigrants to blend in with the existing Creole population. The other two groups made up a quarter of the city’s population. The Irish who arrived in the late 1840s and 1850s were mostly immigrants fleeing the Irish potato famine and were less prosperous than earlier Irish immigrants. These newer immigrants often did difficult and dangerous work like digging canals and building levees, replacing enslaved people in these tasks. The German immigrants of this time were refugees from political unrest in the German states. They often competed with free Black men for skilled labor jobs, especially in the building trades. Both immigrant groups were subjected to abuse by the anti-immigrant American Party (also known nationally as the Know-Nothing Party), which controlled city politics from 1854 through federal occupation.

How did New Orleans residents feel about secession? How did the rest of Louisiana view secession?

Only 25 percent of New Orleans voters turned out for the presidential election of 1860, yet the results were revealing. John Bell, the Constitutional Union Party candidate, won the city with just 4,978 votes. Democrat Stephan Douglas received 2,967 votes. Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge received 2,533 votes. New Orleans voters overwhelmingly supported unionist candidates, though Abraham Lincoln, candidate for the Republican Party, wasn’t on the ballot anywhere in Louisiana. Ultimately Breckinridge won the vote for the state of Louisiana. After Lincoln won the national election, Louisiana Governor Thomas Moore called for a convention to consider Louisiana’s secession from the Union. Louisiana’s vote to secede from the Union on January 26, 1861, confirmed the state’s reliance on a social and economic system supported by race-based slavery that was threatened by the new Republican Party, which sought to block the expansion of slavery in US territories.

In contrast to the national American Party, the New Orleans Know-Nothings embraced secession. New Orleans Mayor John T. Monroe (elected in 1860) was a secessionist and Confederate supporter. However, there were a lot of Northern-born voters living in New Orleans who didn’t support the Confederacy. And there were many immigrants who resented enslaved people and enslavers alike, who were ambivalent about secession. These divisions would come to the surface under federal rule.

What events led to the fall of New Orleans?

Due to its geographical location as the outlet for goods produced throughout the entire Mississippi River valley (including cotton bound for Europe), New Orleans’s capture was crucial for the Union. Union commander-in-chief Winfield Scott devised the Anaconda Plan, which called for suffocating the Southern economy with a naval blockade of the ports along the Gulf Coast and gaining control of traffic down the Mississippi River. The plan would divide the South and shut off access to Texas grain and wartime supplies from Mexico.

Commander David Dixon Porter of the Union Navy had served in the blockade fleet in the Gulf of Mexico. After gathering intelligence, he came up with a plan to capture New Orleans. Fort Jackson and Fort St. Phillip, which were located downriver from New Orleans, would be destroyed by mortar fire from gunboats. Doing so would secure the Mississippi River for the Union Navy. The naval fleet would then proceed upriver and turn its guns on the city of New Orleans. Even with a fleet of seventeen warships with immense firepower, the plan was a daring one. Forts Jackson and St. Phillip were on opposite sides of the river, each in a position to destroy the Union’s wooden ships. To slow the ships down and make them more vulnerable, the Confederates laid a chain across the river laced with sections of floating hulls from old schooners. The forts themselves were built of sturdy brick and mortar. According to historian Shelby Foote, everyone knew that one gun in a fort was worth four on a ship. There was also the disturbing rumor that the Confederates were constructing two giant ironclad ships in the city, which could easily destroy the wooden fleet.

Nevertheless, the Confederate position was hardly ideal. The commander of New Orleans defenses, General Mansfield Lovell had only three thousand troops, while the Union Navy at Ship Island had eighteen thousand men under Benjamin Franklin Butler. Eleven hundred troops manned the Confederate forts, many of them foreigners forced to serve. The two ironclads were far from finished because of labor shortages and a lack of materials.

Sixty-year-old Captain David Farragut served as commander of the Union naval fleet. Farragut agreed to Porter’s plan to destroy the forts by mortar, and firing began on April 18, 1862. After ninety-six hours and thirteen thousand shells, the forts were still intact with only four of the defenders killed and fourteen wounded. Farragut decided to attack the forts with his fleet, much to the frustration of Porter, who thought the forts should be destroyed before the fleet advanced to the city. Porter was worried that Farragut’s approach would leave Butler’s eighteen thousand troops waiting at Ship Island virtually unprotected when they advanced upriver. On the night of April 20, two Union gunboats withstood gunfire from the forts as well as a fire raft sent by the Confederates. However, they were able to secure an escape by releasing one of the chains from a floating hull.

In the early morning of April 24, Farragut gave the order to advance in three groups. The first group passed through the gauntlet. Farragut’s flagship Hartford ran aground on a mud flat and caught fire from a fire raft, but it managed to escape and put the fire out. Among the Confederate flotilla were gunboats, an armored rammer, and the sidewheel steamboat Governor Moore, which sank the Union ship Varuna. Still, the Confederate fleet was scattered, and those that tried to attack (like the Governor Moore) were sunk. Farragut’s forces lost the Varuna and three gunboats, but the rest passed through. Despite massive firepower coming from both forts and ships, casualties were low. Some thirty-nine Union troops were killed and 171 wounded. The Confederate fleets saw approximately 140 Confederates killed and wounded, and the Confederate forts saw eleven killed and 171 wounded. Yet New Orleans was now undefended. Lovell had withdrawn his troops, and all the fortifications above the city were deserted. Porter continued to attack the forts with mortar fire, while two hundred men under Butler’s most able officer, Godfrey Weitzel, navigated the back bayous and marshes that surrounded the forts.

Confederate General Johnson Kelly Duncan had no choice but to surrender both forts to Porter. According to historian Gerald Capers, four days after Farragut’s fleet passed the forts, “half of the Jackson garrison spiked their guns, mutinied[,] and left in small boats.” Most that remained wanted to surrender, emphasizing the fact that the Know-Nothing Confederate regime in New Orleans did little to inspire the loyalty of foreign-born troops.

What challenges did Benjamin Butler face during his tenure as Commander of the Department of the Gulf, and how did he respond?

While Butler accomplished a great deal in the nine months of his tenure as Commander of the Department of the Gulf, he is best known in New Orleans for hanging the gambler William Mumford and for issuing his notorious “Woman Order.”

As the Union Navy negotiated with Mayor Monroe’s administration over the surrender of the city, Mumford pulled down the United States flag, which had flown over the US Custom House since the navy’s arrival on April 26. Mumford then proceeded to tear up the flag and distribute pieces to a crowd that had assembled to watch. When Butler arrived to occupy the city on May 1, he vowed to make an example of Mumford and subsequently had him tried and publicly hanged. The Confederate government in Richmond was outraged and ordered Robert E. Lee “to demand an explanation from [Butler’s superior General Henry] Halleck for the outrageous execution of a Confederate citizen for an act committed before the city was occupied.” However, Butler’s Order 28—in which he proclaimed that New Orleans women who insulted federal troops would be treated “as women of the town plying their avocation” (in other words, as prostitutes)—drew reactions as far away as London, with British Prime Minister Viscount Palmerston commenting, “an Englishman must blush to think that such an act has been committed by one belonging to the Anglo-Saxon race.”

Butler was concerned about maintaining order in New Orleans, and to do so he imposed censorship, closed churches and newspapers unsympathetic to the Union, and imprisoned citizens suspected of sedition. Another objective was to affect a social revolution. He viewed the Civil War as a class war to liberate both the enslaved and the white working man. In his departing letter to the people of New Orleans, Butler wrote, “I saw that this Rebellion was a war of the aristocrats against the middling Men, of the rich against the poor; a war of the landowner against the Laborer; that it was a struggle for the retention of power in the hands of the few against the many; … I therefore felt no hesitation in taking the substance of the wealthy, who had caused the war, to feed the innocent poor, who had suffered by the war.”

Butler’s ordinances to provide relief for the poor were as politically calculated as necessary. New Orleans was a city that survived through commercial activity, and the federal blockade effectively shut down the port—the engine that drove the New Orleans economy. Imports shrank from a pre-war value of almost $156 million to just under $30 million by 1862. Butler responded to the economic crisis by setting up a welfare state. Immediately after occupation he issued Order 25 to alleviate “the deplorable state of destitution and hunger of the mechanics and working classes of the city” by taxing individuals and businesses that had contributed to the former Confederate government. The taxes collected through Order 25 allowed the military government to employ two thousand men at 50 cents a day cleaning up a city scattered with filth and dead animal carcasses. Still, the economic trouble of the city’s poor was such that Butler also issued Order 55, which put eleven thousand families, most of whom were Irish and German, on welfare.

Butler saw the disaffected working class as an opportunity to raise unionist regiments. In addition to the existing regiments that absorbed white volunteers, Butler formed two white infantry and two cavalry regiments by the fall of 1862. He also formed three regiments of free Black and formerly enslaved men. Butler increased the size of his army from 13,700 to 17,800 “trained and disciplined men.”

Butler proved to be an able administrator. He fed the hungry, employed the jobless, and rid the city of yellow fever through a comprehensive cleaning and quarantine program. Nevertheless he lacked military prowess. After a Union victory at Baton Rouge, Butler ordered the city evacuated because he feared an attack on New Orleans. The only other military action during Butler’s tenure was driving Confederate forces out of Lafourche Parish. Butler thought that the Union’s Army of the Gulf was too small for conducting a major campaign.

When Butler was relieved of command in late 1862, it wasn’t due to military cowardliness. It was largely that he had become a political problem for the Lincoln administration by aggressively pursuing foreign diplomats suspected of hoarding specie (money in coin form) for the Confederacy. After accusing the Dutch consul Amedie Conturies of keeping $800,000 in Confederate silver, he also charged the French consul with holding $400,000 in specie that had been used to purchase Confederate uniforms. The Dutch ambassador protested to Secretary of State William Seward that Butler had violated diplomatic immunity, and the evidence suggests that Seward advocated for Butler’s recall. The Lincoln administration took great pains not to alienate European powers, since recognition of the Confederacy by Britain or France would legitimate the Southern cause.

How did the Free State Movement affect Louisiana politics?

General Nathaniel P. Banks replaced Butler in Louisiana, and like his predecessor, he was a self-made man. In the 1850s Banks enjoyed rapid success as a Know-Nothing, serving as governor of Massachusetts and as Speaker of the US House of Representatives. Like Butler, he received a political appointment to the rank of general. Yet while Butler encouraged social revolution, Banks preferred a moderate course in the hope of luring the population into supporting a reconstructed Louisiana. After Banks took over as commander of the Union’s Department of the Gulf in December 1862, he immediately undid some of Butler’s harsh directives by reopening churches closed for Confederate sympathies, freeing political prisoners, and returning property sequestered by the Union Army. In a move that Butler would later characterize as most “unmanly,” Banks decommissioned Black Union officers after they had distinguished themselves at Port Hudson.

Banks is often criticized for not bringing Louisiana back into the Union as a free state, although he spent most of his time on military campaigns in 1863 and 1864. According to historian Ted Tunnell, Banks’s time in the field in his first year was extraordinary: “He recaptured Baton Rouge in December, led his army up the Bayou Teche and the Red River in the spring, captured Port Hudson in July after a siege, and that fall campaigned in Texas.” In the spring of 1864, Banks tried to take control of northern Louisiana from the Confederacy in his ill-fated Red River Campaign, which resulted in his defeat at the hands of the Confederate Army at Mansfield, thirty miles below Shreveport.

The Free State Movement was an effort by New Orleans unionists to restore Louisiana to the Union. As Tunnell points out, New Orleans unionists were outsiders, for “fully 70 percent of prominent unionists in the New Orleans area came from the North or abroad.” Unionists ranged from radical abolitionists to conservative pro-slavery unionists. The leader of the Free State Movement was the lawyer and Bavarian immigrant Michael Hahn, whom Banks saw as someone the Lincoln administration could deal with. Hahn had escaped the Confederate draft because of a clubbed foot, but unlike other unionists, he didn’t leave when New Orleans was a Confederate city, nor did he take the oath of allegiance. As a nineteenth-century liberal, Hahn opposed the planter elite but rejected the radical concept of racial equality.

The working-class equivalent of the Free State Movement was the Working Men’s National League, made up of native-born and immigrant laborers. While they wanted to destroy the “Slave Power” (plantation owners), they weren’t abolitionists, nor did they support equality for free people of color. Workers held class resentment against the planters and didn’t want the competition of free Black labor. As New Orleans’s “craft workers saw their political and economic opportunities eclipsed by slavery and slave owners,” writes historian Eric Arnesen, the “hatred of slavery and the slave frequently became one.” By 1863 New Orleans labor could oppose Know-Nothingism, free Black labor, and slavery without contradiction.

Lincoln wanted to reconstruct the South with his 10 Percent Plan, whereby, if 10 percent of the number of voters who had voted in the 1860 election formed a loyal government and submitted a state constitution acceptable to Congress, the state would be readmitted to the Union. Louisiana would be the test of Lincoln’s 10 Percent Plan, as well as his greatest hope. To implement the plan, Banks called for both the election of a governor and the drafting of a new state constitution for the spring of 1864. Banks endorsed Michael Hahn as a moderate candidate.

Hahn was a man of great courage. He was severely wounded at the 1866 massacre in New Orleans at Mechanics Hall on Canal Street for endorsing Black suffrage. However, in the gubernatorial election of 1864, he appealed to white labor by railing against the planter class, as well as by accusing the free people of color of having Know-Nothing sympathies. Essentially the moderates of the Free State Association wanted to break the power of the planters as a political force and expand the power of urban labor but deny the vote to free Black men. In an election that only included the lower third of the state, Hahn won 54 percent of the vote in a three-man race by gaining the support of groups such as the Working Men’s National Union League, the Mechanics Association, the Crescent City Butcher’s Association, the Working Men of Louisiana, and the German Union. Hahn’s election was a significant proving ground for Lincoln’s 10 Percent Plan, with more than 20 percent of the voters from the 1860 election participating in the election.

How did free people of color respond to the Louisiana Constitution of 1864?

The Louisiana Constitution of 1864 based representation in the legislature on the voting white population rather than the total population, effectively excluding both free men of color and formerly enslaved men (freedmen). The constitution expanded the voting franchise to all white men, abolished slavery, set a minimum wage and a nine-hour day for workers involved in public works projects, and called for free education for all children. However, twenty-four thousand free Black and formerly enslaved men from Louisiana had fought for the Union Army, and so veteran officers James Ingraham and free man of color Arnold Bertonneau saw this moment as an opportunity to secure equal rights for all Black men. After Banks ignored their requests, Bertonneau and another free man of color, J. B. Roudanez, carried a petition demanding Black suffrage to President Lincoln and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. More than anyone, Lincoln understood the importance of the 180,000 Black troops who had served in the Union Army (roughly 10 percent). He wrote a letter to Governor Hahn asking that the vote be extended to “the very intelligent and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks.” Banks and Hahn, realizing their political situation, attempted to hammer out a compromise with the legislature—free education for all children and a provision that would give the legislature the power to grant Black suffrage in the future. However, the compromise was unacceptable to the free Black community. Charles Sumner would later let the Louisiana Constitution of 1864 die in a congressional committee.

What has been the legacy of the fall and federal occupation of New Orleans?

One can argue that Union occupation of New Orleans was comparatively benevolent. Though the population grumbled, there was no uprising. During Banks’s tenure, socializing between Union troops and the local population was common, and after the fall of Vicksburg in 1863, the New Orleans economy recovered some of its former vibrancy.

In the late nineteenth century, New Orleans became a key player in spreading the Confederate Lost Cause mythos. The Lost Cause was a belief system of white Southerners after the Civil War that the war was about states’ rights and not about slavery. Lost Cause ideology maintained that the South wasn’t really defeated militarily but simply overwhelmed by the superior numbers of an industrialized North. The founding of the Southern Historical Society by ex-Confederate officers in New Orleans in 1869 and the dedication of both the Robert E. Lee monument in 1884 and the Confederate Memorial Hall in 1891 had the same objectives of morally justifying the Confederate cause and celebrating Southern military prowess. Figures such as the dashing Creole general P. G. T. Beauregard, along with the twenty thousand New Orleans citizens who took up arms for the South, linked the city with both the Confederate nation and its enduring myth.

Unlike Atlanta, Charleston, and Baton Rouge, New Orleans suffered virtually no physical damage from the war. But the humiliation of occupation from 1862 through the end of Reconstruction in 1877 fueled a resentment that placed New Orleans—in the memory of its citizens—as a city firmly entrenched in the Confederacy. The story of New Orleans under federal occupation, however, is far more complex than the Confederate mythology that dominated both public discourse and even scholarly discourse for decades after the war. During the years of Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, the memory and bitterness of federal occupation became part of the city’s cultural lore. Hence, the history of federal occupation of the South’s largest and most diverse city continues to be controversial.