Francisco Bernard

Like many painters of his time, Francisco Bernard spent the winters in New Orleans and traveled as an itinerant portrait painter during the summer.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

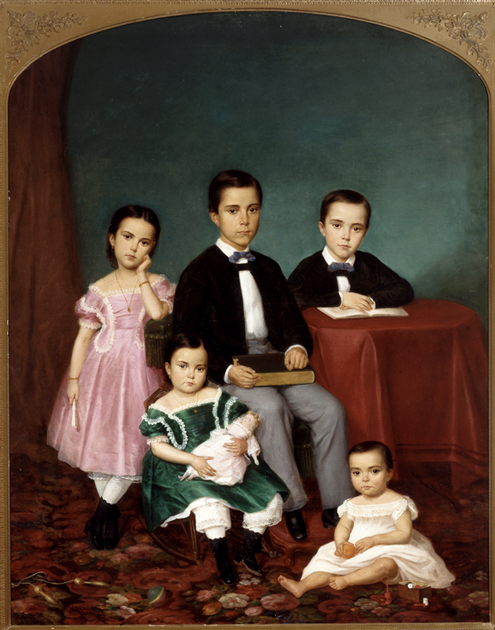

Group portrait of Creole Children. Bernard, François (artist)

Like the photograph, Francisco Bernard’s portraits were designed to appeal to patrons’ growing interest in straightforward, mimetic portraiture during the 1850s, providing a truthfulness of representation that is on the surface not open to question. Bernard’s style can be described as cold and correct, marked by sharp transitions between the shadows and highlights. As New Orleans artist and curator John Burton Harter suggested, Bernard’s paintings mimic the daguerreotype’s tonal variations. Like those of George David Coulon, Bernard’s portraits are direct and forthright, eschewing the more diffuse and idealized portraits of Jacques Amans or the compositional ambition of John-Joseph Vaudechamp or Francois Joseph Fleischbein.

Bernard’s portraits are more complex than they appear on the surface. Although Bernard’s audience seems to have appreciated how closely he mimicked the emerging art of portrait photography, their growing insistence on exactness signals anxiety about how best to capture and preserve a subject’s authentic appearance. With appearance measurable against the “perfect transcription” of the daguerreotype, to paint a portrait that departed from the photographic standard of truthful representation suddenly seemed, to level-headed New Orleans merchants, a little disingenuous and possibly immoral. Perhaps for this reason, Bernard took few pains to disguise the less attractive attributes of many of his sitters’ countenances. Old age, corpulence, and even disfigurement receive the same dispassionate artistic treatment as youth, proportion, and beauty. Bernard seems to have recognized this, advertising his services in 1860 by noting that he “will paint pictures with same care and exactitude as in the past.” Just as photography had upped the ante for Vaudechamp and especially Jules Lion a generation before, no detail, no matter how particular or unflattering, escaped Bernard’s observation.

There is some confusion over Bernard’s identity. Contemporaries generally referred to him as Francisco, but his given name was more likely François. He may have been born in Nîmes, France, on February 8, 1814. Others have suggested that he was born in Bordeaux and studied in Paris, and exhibited at the Salons of 1859, 1861, 1863 (the year Édouard Manet created a scandal with Olympia) until 1865. The Benézit Dictonary of Artists, first published in 1911, lists Jean-François-Armand-Félix Bernard with roughly the same life dates (1829–1894), stating that he studied with Jean-Claude Bonnefond (1796–1850) and Jean-Paul Flandrin (1811–1902) at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Jean-François-Armand-Félix won the Grand Prise de Rome in 1854 for the mythological landscape Lycidas et Moris, based on the ninth epilogue of Virgil. Francisco Bernard’s crisp style and eye for anecdote compares to Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin’s landscapes and the spare drawing style advocated by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, calculated to appeal to petite-bourgeois tastes of the late nineteenth century. However, Benézit makes no mention of Louisiana scenes. The Swedish immigrant artist Bror Wikstrom wrote in 1907 that Bernard was a “pupil of Paul Delaroche—was here in 1858 and left about 1872 for South America.” Mantle Fielding wrote in 1958 that “nothing is known of this artist except that the painted portraits and landscapes of merit in New Orleans at intervals from 1848 until 1867.”

Bernard may have visited New Orleans as early as 1848, based on a few portraits of Louisianans from that period. It is possible, of course, that New Orleanians sought his services in France, as was the case with Robert Monvision or Eugene Devaria, artists who did not visit New Orleans but were highly sought after by Louisiana residents visiting Paris. A newspaper advertisement in the New Orleans Bee in December 1856 placed him in the city during the previous summer. Bernard exhibited at Wagener’s (1867); the Grand State Fair (1868); and Wagener and Meyer’s (1869–1871), described in an 1870 advertisement as “the resort of connoisseurs and amateurs”; and the American Exposition (1885–86). He was awarded a silver medal for the “best head in oil” at the Grand State Fair in 1869. The same year, at Wagener and Meyer, he showed The Indian Camp near Mandeville and a portrait of Mrs. Pinckey Smith, “which created a lot of sensation,” according to the Daily Picayune. Bernard was indeed in Mandeville during part of the Civil War, though he appears to have also been in France. Bernard was back in New Orleans in February 1867, and gave drawing lesson to Alexandre Alaux in 1872. He is also recorded working in New Jersey in the 1870s, though he may only have sent paintings for an exhibition. He is listed in city directories as having a studio “above the Crescent City Bank,” at the corner of Carondelet and Canal Street. After this, he lived at 146 Customhouse Street, above “over the bookstore of Mr. White,” in 1860, 1866, and 1868–1870. He lived at 24 Dauphine in 1871, but returned to Customhouse Street the following year. Bernard moved to Peru about 1875.

Bernard painted a number of landscapes in New Orleans—notably Indian Encampment—but most of his extant paintings are direct, businesslike, and scrupulously detailed portraits. Like many Louisiana artists of the 1850s and 1860s, including Gustave Moses and Theodore Sidney Moise, Bernard relied on the new technology to create portraits with disarming verisimilitude. For example, Bernard painted a post mortem portrait of Josephine Lauve in 1865 from a daguerreotype, and also created photo-paintings, a precursor to the ubiquitous crayon portraits of the 1870s through the early 1900s. He specifically mentioned the hybrids in an 1867 advertisement in the Bee: “As portraits in oil and pastels are not available to every purse, Mr. Bernard will also paint photographs.” In the sour post-Civil War economy of the South, the artist seems to have struggled. Indian Girl, shown at Wagener and Meyer in 1870 together with landscapes by “that clever Southern artist Richard Clague,” was said to be “worth treble the price asked for it.”

The Louisiana State Museum has the largest collection of Bernard’s paintings, including: James Gallier Jr., 1868; Victor Viosca, ca.1862–1865; Jean Baptiste Plauche Jr., 1861; M. Gerdere, 1853; L. Gardere, 1853; Captain J. Pinkney Smith; Mrs. Pinkney Smith, 1870; Charles Allard Duplantier, 1869; F.W. Wagener, 1867; Mrs. Wilhelmina Braun Wagener, 1867; Clara Wagener, 1865-70; Clara Wagener; two versions of Mrs. Michel Bernard Cantrelle, 1862; Mr. John McDonald Taylor, 1860-69; Mrs. Angelle (Magin) Puig, 1848; Mr. Forstall, 1861; Colonel Samuel Boyd, 1867. Chocktaw Village near the Tchefuncte is in the collection of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. Other institutions with significant holdings include The Historic New Orleans Collection, Ogden Museum of Art, and New Orleans Museum of Art.