Free Southern Theater

Founded in 1963, the Free Southern Theater was designed as a cultural and educational extension of the civil rights movement in the South.

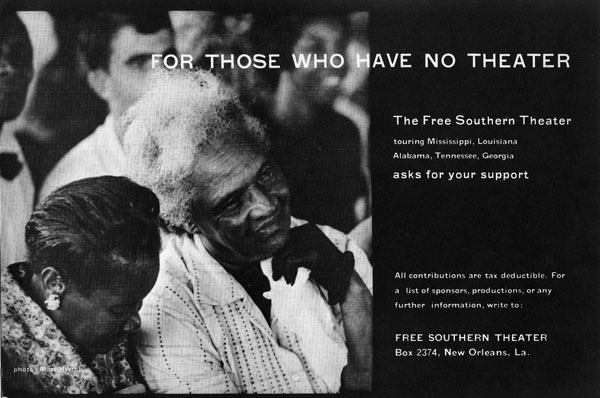

Courtesy of Amistad Research Center at Tulane University

Free Southern Theater - For Those Who Have No Theater. Unidentified

Founded in 1963, the Free Southern Theater was designed as a cultural and educational extension of the civil rights movement in the South. It was closely aligned with the black arts movement of the 1960s and 1970s and, more specifically, the black theatre movement. The leaders of the movement, John O’Neal, Doris Derby, and Gilbert Moses, aimed to introduce theater to southern communities that had little familiarity with it. With both political and aesthetic objectives, the group aspired to validate positive aspects of African American culture while providing a voice for social protest. Though it was founded at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, the theater eventually put down roots in New Orleans.

Origins of the Free Southern Theater

When they met in 1963, O’Neal and Derby were both field directors for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Jackson, Mississippi. One of its foundational documents reflects the Free Southern Theater’s interconnection with the civil rights movement. In A General Prospectus for the Establishment of a Free Southern Theater, the leaders outline their key objectives as the stimulation of “creative and reflective thought among Negroes in Mississippi and other Southern states.” Within the “Southern situation,” they hoped to find “a theatrical form and style . . . as unique to the Negro people as the origin of blues and jazz.”

Realizing that they lacked the experience to successfully organize a theater troupe on their own, the leaders of the Free Southern Theater recruited Tulane University professor Richard Schechner. Schechner eventually served in roles ranging from advisor to chairman of the board of directors. With an initial company of three African American and five white actors, the Free Southern Theater toured rural Mississippi and Louisiana. Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot was one of its first plays. Within two years, the Free Southern Theater had grown to twenty-three members, including a small administrative staff. By 1966 all actors were African American and the plays—featuring works by Amiri Baraka, as well as Free Southern Theater members—were written almost exclusively by African Americans. This paralleled a shift toward black nationalism, with its emphasis on separatism, within the civil rights movement itself.

Move to New Orleans

Under financial duress, the Free Southern Theater moved to New Orleans in late 1965, hoping to attract more financial support from the city’s burgeoning black middle class. The move caused some discord among members who felt that the group was abandoning its initial goal of bringing cultural events to poor, rural communities. After Gilbert Moses, Richard Schechner, and John O’Neal left the Free Southern Theater in 1966, Tom Dent came to New Orleans to lead the troupe and almost immediately impacted the administrative and artistic direction of the Free Southern Theater. Dent, with the help of Kalamu ya Salaam (aka Val Ferdinand), implemented a community writing and acting workshop, BLKARTSOUTH, in which members began to write and produce scripts. Some of these plays were then incorporated into the company’s repertoire.

Gilbert Moses and John O’Neal eventually returned to the Free Southern Theater and resumed leading roles. Though Tom Dent eventually left his official role, the three remained key creative forces within the company. In addition to developing original material from BLKARTSOUTH, the Free Southern Theater adapted the works of well-known playwrights for their own purposes. The company sparked controversy, for example, when actors performed Waiting for Godot in whiteface. They also adapted Martin Duberman’s In White America to include the murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman.

Two plays by John O’Neal embody the spirit of the Free Southern Theater at its apex. When the Opportunity Scratches, Itch It comments on the power dynamics among different social classes in the African American community. Where Is the Blood of Your Fathers? utilizes a variety of historical texts such as Frederick Douglass’s autobiography and David Walker’s Appeal to dramatize episodes in the life of a slave. In accord with the company’s educational objectives, performers encouraged audience interaction and performances were routinely followed by audience discussions.

Decline and Legacy

Funds were always in short supply at the Free South Theater, in part because of its commitment to providing free admission to performances. As a result, troupe administrators constantly developed fundraising activities. The Rockefeller and Ford Foundations contributed sizable grants to help the company meet its nearly $100,000 annual budget. Arthur Ashe, Bill Cosby, Harry Belafonte, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Julian Bond were also involved with benefit drives, and Langston Hughes contributed the troupe’s first-ever monetary donation. Despite the endorsement of these celebrity benefactors, the theater lost both creative momentum and financial support at the dawn of the civil rights era.

Despite its demise, the Free Southern Theater influenced community-based radical theaters across the country. Several troupe members contributed to the influential but short-lived journal Black Theatre. In 1985, John O’Neal organized a Free Southern Theater second line and symposium to celebrate and commemorate the lasting legacy of the company. O’Neal’s Junebug Productions is widely considered the successor to the Free Southern Theater.